Why we’re failing to close the gap on Indigenous disadvantage

This is because, almost 27 years since John Howard’s famous “practical reconciliation” speech, his sentiments dominate.

“Reconciliation will not work if it puts a higher value on symbolic gestures and overblown promises rather than the practical needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in areas like health, housing, education and employment,” Howard said at the Australian Reconciliation Convention in May 1997.

In the past five weeks of the campaign for an Indigenous voice enshrined in the Constitution, Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney described the advisory body as “practical reconciliation”, once in an essay in The Australian and again at an economic development conference in Perth. This did not cut through.

Instead, Australians voted against putting into the Constitution what The Australian’s editor-at-large Paul Kelly termed “a group rights body, a political body”.

Anthony Albanese does not talk about Indigenous empowerment anymore. He has said as little as possible on Indigenous affairs since the referendum was defeated on October 14. This could place the government in a predicament on a big agenda item – the national agreement on Closing the Gap. The decade-long agreement of all states, territories and the commonwealth purports to be about power sharing with Indigenous communities. It is a promise to take advice from Indigenous peoples at a local and regional level. Scott Morrison – who was known to oppose a constitutionally enshrined voice – signed this pledge for governments to share decision-making with Indigenous communities. If it sounds familiar, that is because there is already a proposal for that in the Calma-Langton report of 2021. It recommended states and territories legislate regional voices and engage with them.

Some think the Closing the Gap agreement is crying out for legislated local and regional voices to help carry out its work. Others think it has no hope of succeeding without that kind of structure. Peter Dutton has previously expressed support for Indigenous voices at this level, but not a national voice.

Morrison was a vocal supporter of empowering Indigenous communities to make decisions with governments in the Closing the Gap agreement. In parliament in February 2020, Morrison lamented a decade of failure under the old Closing the Gap agreement and said: “We perpetuated an ingrained way of thinking, passed down over two centuries and more, and it was the belief that we knew better than our Indigenous peoples. We don’t. We also thought we understood their problems better than they did. We don’t. They live them. We must see the gap we wish to close, not from our viewpoint, but from the viewpoint of Indigenous Australians before we can hope to close it, and make a real difference. And that is the change we are now making, together with Indigenous Australians through this process.

“We thought we were helping when we replaced independence with welfare. This must change. We must restore the right to take responsibility. The right to make decisions,” Morrison said.

“The right to step up. The opportunity to own and create Australians’ own futures. It must be accompanied by a willingness to push decisions down to the people who are closest to them. Where the problems are, and where the consequences of decisions are experienced. That is what we must do.”

Four years later, the Productivity Commission’s review of Closing the Gap says none of this is happening. The PC report published on Wednesday takes readers into the procedural world of intergovernmental agreements. The PC has examined state government implementation plans that are supposed to be strategies and exposed them as just laundry lists of current activities.

The PC report is 99 pages. There are another 430 pages of supporting papers and 91 submissions, including from state governments in their own defence and from Indigenous organisations that have what is lately called “lived experience”. They have seen what works and fails.

It is painstaking work that gives detail we will never get from question time, from National Press Club speeches or at the media events of politicians. The report makes four recommendations including that governments move now to create independent watchdogs with “robust” legislative powers to examine progress under the agreement. It says government ministers should meet regularly with relevant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peak bodies, so that they can hear directly from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people about their priorities and perspectives before making decisions. Some Indigenous leaders do not believe the agreement can succeed on the strength of consultations with peak Indigenous bodies, many of them national. They believe bureaucrats need to deal directly with individual communities on local decisions and that cannot be left up to the goodwill of individual public servants. A system is necessary.

There are pockets of hope and success in the review but the Closing the Gap story is about misery, violence, unmet potential and early deaths. That is why this debate is high stakes. Rheumatic heart disease stalks Indigenous children, diabetes rages in central Australia at the highest rate in the world and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children are 34 times more likely to be hospitalised due to violence than non-Indigenous women and children. In Australia, Indigenous women are six times more likely to die as a result of family violence than non-Indigenous women.

Under the agreement, only four out of 17 targets are on track to be met by 2031. In some cases, results are worsening. For example, there was an increase in the rate at which Indigenous juveniles were jailed in 2023 and the proportion of Indigenous youth in Australia’s very remote communities who have a job, a traineeship or study fell below a third.

The PC report says some governments had demonstrated a willingness to partner and share decision-making in some circumstances. However, governments were not yet sufficiently investing in partnerships or enacting the sharing of power that needed to occur if decisions were to be made jointly. There appeared to be an assumption that “governments know best”, which was contrary to the principle of shared decision-making in the agreement, the PC said.

The PC found the public service was so massive that departments or agencies with responsibility for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy lacked the authority or influence “to motivate other larger agencies to do what has been committed to in the agreement”. In other words, Indigenous communities are not the only ones being ignored. Sections of the bureaucracy that are trying to do their jobs are also getting ignored.

Empowered Communities is an Indigenous organisation that understands how difficult it is to get the ear of decision makers but that when it happens, the results are extraordinary. This alliance of 10 Indigenous regions has lobbied hard for the opportunity to review funding decisions with government. In 2017, the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet agreed to sit down with Empowered Communities representatives in Redfern and La Perouse to look at government spending on Indigenous programs there.

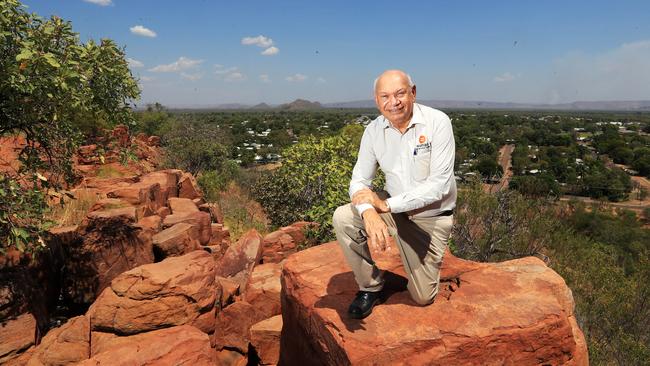

“In its first year more than half of the funding considered was found to be duplication and misdirection, that is, an amount of $1.01m out of $1.98m,” Empowered Communities chairman Ian Trust told the PC.

In Trust’s home town of Kununurra in the east Kimberley, Empowered Communities helped the government find waste among programs totalling $3.25m. This meant that money could be redirected to a local early childhood program.

Trust said Empowered Communities was devastated by the failure to achieve a Yes vote at the referendum and the lost opportunity this represented to shift the dial on Indigenous disadvantage. “Working in partnership – particularly with the Australian government – Empowered Communities has made some important headway and implemented significant groundbreaking innovations since 2015,” he told the PC.

“However, gains have been hard won and are only piecemeal. Governments’ commitment to pursue an Indigenous empowerment, development and productivity approach remains too weak and is relatively fragile.

“Even with enduring, high-level bipartisan support for our approach over eight years, all progress made by Empowered Communities has been highly, and unacceptably, dependent on the goodwill and commitment of individuals within the bureaucracy and at the ministerial level – and key personnel are constantly changing.”

Empowered Communities does not see how the current Closing the Gap agreement can change this. It points to “a complete absence of any system or method whatsoever for Indigenous empowerment/responsibility/self-determination from the ground up, despite near universal acknowledgment over a long period that this is a vital missing ingredient for success”.

“Now we have a top-down, government-led Closing the Gap approach since 2008, which provides only a commitment rather than a method for Indigenous empowerment,” Trust told the PC.

Trust wants legislation that would allow Indigenous communities to opt into mutual responsibility agreements with governments spanning 10 years, longer than the electoral cycle.

“Under the (Closing the Gap) agreement there is an ongoing and complete disconnect between high-level policy and decision-making in Canberra, Brisbane, Darwin and Perth etc, and any changes on the ground actually impacting Indigenous families and communities,” Trust said.

“Policy partnerships are developed at the jurisdictional and national level. Pathways for providing local-level input into these partnerships are unclear. The gap will not close at the national level or at jurisdictional level. It will close in households, in our school rooms, on the tracks and streets in our communities. Reform must happen at the local and regional level if we are to see the changes we all desire.”

When the Albanese government presents its Closing the Gap annual report in parliament on Tuesday, Indigenous leaders predict the language will be Howard-esque. They expect little or no talk of Indigenous rights and a total focus on practical measures.