Why NZ’s all black mood bodes ill for Ardern ahead of election

Frustration and anger at a flailing All Black side is emblematic of NZ’s crisis of confidence in its government and could prove disastrous for Jacinda Ardern at the 2023 poll.

Dark and stormy clouds are forming above New Zealand – and not just of the climatic kind.

Amid an especially bracing few months that have brought frigid temperatures and regional flooding, Kiwis are also having to contend with ill winds of another sort – social, economic and sporting – that are sweeping the nation and causing rising public disquiet.

For many New Zealanders, most winter troubles can be soothed by the inevitable victories of the national rugby team – the venerated All Blacks – which are notched up with great regularity and aplomb.

But Kiwis’ faith in the national team has taken a hammering recently, further fuelling the country’s feeling of unease.

The All Blacks are presently suffering an extraordinary run of losses – including most recently to Ireland – under an unpopular coach and with few near-term prospects of improvement in sight.

Until relatively recently, the ABs, as Kiwis call them, were safety ensconced as the world’s best rugby side. Now the team is ranked fourth and in real danger of sliding further down the rankings should its current poor form persist – as many expect it will.

Frustration and anger at the sputtering team machine, including how it is run off the field, is only fuelling New Zealand’s unusually dark mood and – most worryingly for Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern – is emblematic of the nation’s crisis of confidence as a whole.

Few countries are so allied to a single sport as NZ is to rugby. The game’s historic grassroots appeal, and longstanding cultural and societal links, are threaded tightly in the nation’s fabric. Indeed, the success or failure of the All Blacks affects the national psyche in ways that few sporting teams do in other countries.

All Black defeats may never have brought down a government but the fortunes of incumbent governments have followed those of the national team with uncanny regularity.

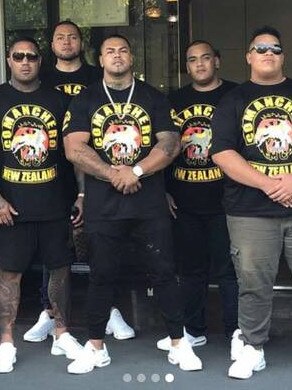

This time around, the country’s disillusion in the team is reflected in similar disillusion in the government, with a protracted cost-of-living crisis abetted by climbing inflation and a low-growth economy, rising Covid cases and hospitalisations under a cracking healthcare system and escalating gang violence – all of which spell potential disaster for Ardern in the polls.

Should the current conditions persist and the country’s mood prove stubborn, as well it might, the next election – to be held in 2023 – could easily shape up as a “change election” that would eject Ardern and her Labour Party from power.

Even if there is the merest hint of change in the air – and there appears to be one brewing – it may be hard to stop it from coming.

Any inescapable indication of looming political change is not yet visible among voters, however. Although polling shows the centre-right opposition National Party – led by Christopher Luxon – pulling ahead of Labour in the party vote, Ardern remains comfortably ahead of Luxon as preferred prime minister.

So far, she remains well-liked by the majority, and her individual brand of empathy and her ability to connect with voters remain effective political tools. As such, Ardern is still thought of by her party as its biggest asset.

However, some commentators are starting to question this thinking amid the array of lingering problems facing the nation and the robust challenge mounted by a revitalised National Party, which has been out of power since 2017.

Ardern’s once celebrated management of Covid has come under increasing criticism, particularly the draconian decision to ban Kiwis overseas from returning home and the slow vaccine rollout which resulted in more lockdowns as the rest of the world was opening up.

Her role in addressing the ultimately violent occupation of the grounds of the New Zealand parliament in central Wellington by groups calling for an end to all pandemic restrictions also came under scrutiny.

Then there are the broken election promises: in 2017, Ardern promised to build 100,000 affordable homes within 10 years: five years later, only 1366 have been built. She promised to lift 100,000 children out of poverty but the number of children in poverty has increased.

The government has now been driven to buy up motel rooms to house homeless families, much to the fury of local NIMBYs. Meanwhile, emissions have increased by 2 per cent since 2018 while net migration has turned negative for the first time in decades as young people flee the country for better opportunities abroad – mostly in Australia.

As her troubles mount, there is growing sentiment in New Zealand that Ardern, like the troubled All Blacks, needs to lift her game.

And, just as there is chatter about who will replace the All Blacks’ coach, there is now growing speculation over who might follow Ardern as party leader. This question has never arisen before, quite possibly because there were no obvious contenders. But should her appeal wane to a point that could endanger Labour’s election prospects, then all bets are off.

Indeed, there has long been speculation in some quarters that Ardern might seek at some future point to leverage her international star power to pivot to an important global role overseas.

It is also worth noting that an unexpected and abrupt prime ministerial change is a recent memory for Kiwis.

In December 2016, at the height of his power and ahead of the 2017 general election in which he was expected to win his fourth term of office, John Key shocked the nation by resigning as prime minister and leader of the National Party. He cited the desire to spend more time with his family at home as a primary reason for his decision. It showed, nevertheless, that even popular leaders can head to the exit.

Ardern and her team have certainly moved to attend swiftly to the country’s social and economic headwinds. Ministers have recently issued plans to crack down on gang activity (new legislation to expand the scope of firearm legislation) and take the sting out of high fuel prices (cutting petrol excise duty and mandating the extension of half-price public transport fares).

Treasury also aims to reduce headline inflation by 0.5 percentage points in the June quarter, even though elevated government spending is seen by critics as stoking inflationary pressures in the first place.

Whether any government measures will provide sufficient comfort to the edgy nation, though, remains to be seen. The longer the problems persist, the more entrenched the county’s mood will be – and the more disillusioned the electorate will become with Labour.

Key, one of the most successful NZ prime ministers in the modern era, saw value in a victorious All Black team in terms of national sentiment but also as a political dividend.

He assiduously aligned himself closely with the triumphs of the All Blacks, and the optics on his frequent visits to the winning changing room and his close embrace of NZ rugby heroes of the day had political pulling power.

Key enjoyed the luxury of having his premiership – from 2008 to 2016 – coincide with arguably the most successful period ever in All Blacks history.

Ardern, however, is not as fortunate. Her All Blacks have been labelled the worst since the game turned professional in 1995.

Political success, after all, is almost always about luck and timing.

Craig Greaves is a freelance writer who spent nearly a decade working for the US State Department advising on New Zealand foreign policy and New Zealand politics.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout