Where is Paul Keating when you need him?

Anthony Albanese’s majority is wafer-thin, and neither he nor his Treasurer is passionate about the sort of economic reforms Australia needs right now.

Next year’s May budget will be the last before the Albanese government seeks re-election. It plans to deliver a small surplus, spruiking its fiscal discipline in doing so, and is avoiding the temptation now to provide cost-of-living relief that stokes inflation and increases the debt.

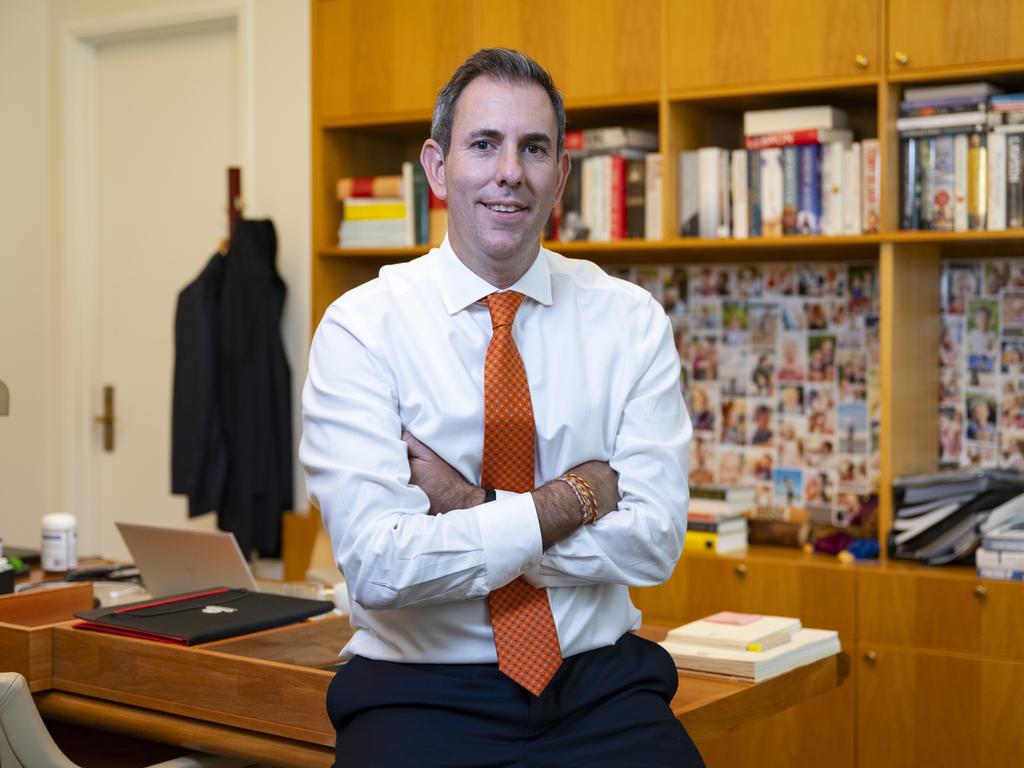

To be sure, the pressure from the backbench has been immense. It is a credit to Jim Chalmers that he has resisted it.

Next year’s budget will deliver the second surplus since Labor took office: two from two after years of promised Coalition surpluses that never materialised. The Treasurer hopes to use the contrast to bolster the government’s economic credentials in response to Coalition attacks that Labor “can’t manage money”.

But once the budget is out of the way, profligacy will likely rule supreme. The government then, and only then, will attempt to buy a second term with election promises the budget can’t afford without wider reform: targeted spending, new tax relief, costly programs designed to show that Labor remains true to its values on climate change and social responsibility.

Expect deficits in the budget out years to balloon from what was presented on Wednesday this week, and from what will be announced in next year’s budget, but without the D-Day of a third budget to account for all the new spending being handed down before polling day. The details will be spelled out only in the aftermath of the next election.

Ironically the centrepiece of tax relief and new spending the Albanese government will use to sell itself to the electorate is income tax cuts legislated before Labor won the election last year. They were supported by Labor in opposition, reluctantly and only after grumbling about the unfairness of the tax cuts.

I’m talking about the stage three income tax cuts that reduce the tax rate for all earnings below $200,000 a year to no more than 30 per cent. They take effect on July 1 next year, meaning many voters will experience a sizeable uplift in their take-home pay in the countdown to the next election.

In the wake of rising inflation, these cuts have become more important than previously thought.

MYEFO highlighted the profound impact of bracket creep in these high inflationary times. It is eroding the take-home pay of many, increasing the disproportionate reliance on income taxes by government and cementing Australia as a high-taxing country relative to other nations.

Reducing income taxes therefore is necessary, notwithstanding the inflationary risks associated with putting more money in the pockets of higher-income earners.

This week Chalmers said: “Returning bracket creep is a worthwhile aspiration for a government.” Critics who concern themselves with the stage three cuts targeting only higher tax brackets need to be reminded the cuts are called stage three for a reason. Stages one and two targeted lower-income earners and were enacted years ago.

University of Western Australia economics professor Peter Robertson says: “The Henry tax review identified a number of distortionary taxes that have crept into the Australian tax system … The stage three tax changes are designed to remove one of these invidious taxes – the effect of bracket creep on people’s incomes. To enhance productivity we need less creep and more clarity.”

Ideally, government would legislate tax brackets moving with the consumer price index, thereby removing bracket creep from the picture entirely. But neither side of politics is likely to do that because bouts of bracket creep are a lazy way for governments to improve their budget bottom line without embracing reforms.

For the implementation of stage three income tax cuts to deliver more than bracket creep relief, they need to be followed up with wider tax reform to simplify the system and address the structural deficit that worsens in the budget out years, courtesy of spending programs such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

This is the difficult economic work Chalmers and the Labor government aren’t willing to embark on. To be fair, neither did the previous Coalition government, despite being in power for nearly nine years.

Labor perennially rules out GST reform. It wouldn’t even let Ken Henry evaluate reforming the GST as part of his tax review during the Rudd years.

Robertson thinks this is a mistake: “A broader-based GST can increase tax income to help implement the stage three cuts while maintaining fiscal balance and not firing up further inflationary expectations. Income support can also be funded by taxes on rents and potentially non-retrospective wealth taxes. It will be interesting to see if the next term of government has the stomach to look at these issues.”

Sadly, I highly doubt it. Modern politics would require the government, if it wanted to pursue wider tax reform, to flag its intentions this side of polling day. Doing so afterwards would be regarded as a broken promise and would be met by partisan criticism, and probably wouldn’t pass the Senate anyway.

If the government took wide-ranging tax reform to the election the opposition would turn the subsequent campaign into a confusing discussion about details, risking Labor’s re-election. Labor doesn’t want to complicate its election messaging, even if the economic need to do so is overwhelming.

John Howard took tax reform to the 1998 election, using his victory as a mandate for its implementation. But he had a thumping majority courtesy of his 1996 election landslide that could be sacrificed at the alter of reform.

Anthony Albanese’s majority is wafer-thin, and neither he nor his Treasurer is passionate about the sort of economic reforms Australia needs right now.

Where is Paul Keating when you need him? Or Peter Costello for that matter? Treasurers willing to do more than preside, cognisant that the window for achieving economic reforms is narrow and closes quickly.

Theodore Roosevelt famously said: “Nothing in the world is worth having or worth doing unless it means effort, pain, difficulty.”

Unfortunately it’s not a mantra many live by in the nation’s capital, where holding on to power matters more than what you do with it. Where winning elections increasingly is seen as the only thing worth doing. As effortlessly and painlessly as is possible.

It’s a recipe for mediocrity.

Peter van Onselen is a professor of politics and public policy at the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.

This week’s mid-year economic and fiscal outlook belled the cat on the government’s political strategy as it counts down to an election in 12 to 18 months. It is an economically contradictory approach, but Labor strategists believe they can sell it politically to voters, and they probably are right.