When we’re talking better off, one man trumps the pool

He may be lagging in the polls, but the US President has one set of numbers more beautiful than any of his predecessors.

Are you better off than you were four years ago?

Ronald Reagan put that question to voters during the presidential debate with Jimmy Carter in 1980. The US had suffered through an oil crisis, and was in the midst of a recession. Most people felt worse off, compared with when Carter was elected in 1976.

Reagan went on to win the 1980 election in a landslide.

His question — “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” — is now considered one of the most important for pundits seeking to predict whether an incumbent will win a second term.

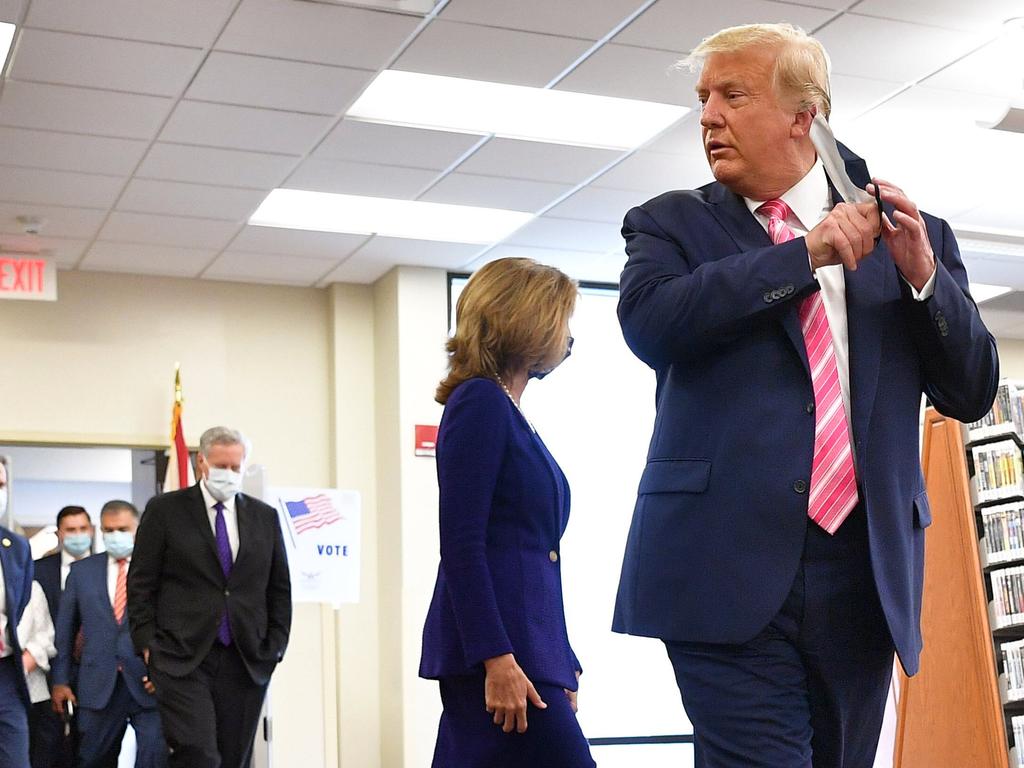

So, how do voters feel after four years of Donald Trump? The answer may surprise you.

The US polling giant, Gallup, put the “better off” question to a random sample of voters shortly before the President was diagnosed with, and recovered from, COVID-19.

In response, 56 per cent said they were better off than four years ago.

On this key question, Trump is therefore doing better than Barack Obama (45 per cent); and he’s doing better than George W. Bush (47 per cent) — both of whom got second terms.

He’s also doing better than Reagan, who redefined landslide when he won 49 of the 50 states upon his return to office in 1984 (his opponent, Walter Mondale, managed to hold onto his home state, Minnesota).

Reagan’s number, after four years, was 44 per cent. Again, Trump’s is 56. And that’s not before COVID. That’s right now.

Gallup says: “No other incumbent president in the past three decades has enjoyed such a high percentage of people saying they feel better about their situation.”

So, if Trump is doing better on this question than his predecessors, why are the polls predicting a Biden landslide?

Jeffrey Jones, who oversees all US polling for Gallup, told Forbes this week that voters won’t necessarily be thinking about their own personal circumstance so much as other matters — such as police brutality or the soaring coronavirus death rate — when they cast their ballot.

“People … care more about what’s going on out there, as opposed to their own situation,” Jones said.

To which others say: ha! The No 1 issue for the bulk of US voters — and Australian voters — is always the economy, and most people experience the economy in a very intimate way.

For example, when Australians think about their personal wealth, they often think about their house: what’s it worth? Or else: can I afford to buy one and then make the repayments?

In the US, workers tend to look more closely at the value of their 401K (it’s like super) or similar investments. Not everyone in the US has a 401K plan, but according to the US Census Bureau, about half of all workers do, and the value of these products has increased by at least 40 per cent, and in some cases by as much as 100 per cent, under Trump.

Doubling a person’s wealth in four years, even on paper, will certainly make them feel “better off” than they were before.

It’s the same with shares: if you’ve been in the market during Trump’s term, you’re very likely in clover. The Dow collapsed in the wake of COVID, but has largely recovered. The S&P 500 — a measure broader than the Dow — is up 47 per cent since Trump’s inauguration.

As for some of the other normally reliable economic indicators, well, the pandemic has played havoc with the data, hasn’t it?

For example, the unemployment rate when Trump took office was 4.7 per cent. By the third year of the Trump administration, it had dipped to 3.5 per cent. Post-pandemic — are they even post-pandemic over there? — it stands at 11.1 per cent.

The fact that a clear majority of voters still feel “better off” than they did four years ago strongly suggests that they don’t hold Trump responsible for soaring unemployment. They blame COVID-19, and possibly China. They may also have enjoyed the Trump stimulus.

Alternatively, voters are looking at other issues, and feeling pleased with Trump’s handling of them. US foreign policy, for example. Many voters are intensely interested in foreign affairs.

Happily, Trump is not.

He makes no secret of the fact that he is not particularly curious about the world. Indeed, it seems to end for him at the front door of the White House.

To put that another way — this one is for close students of John Bolton’s memoir — he probably didn’t know where Finland was.

This weakness — his disinterest — quickly became his strength.

Bob Woodward’s new book, Rage, tells a story about Trump’s defence secretary James Mattis being so anxious about a possible nuclear confrontation with North Korea that he took to sleeping in his clothes in case he had to race to the Pentagon in the middle of the night.

None of the doomsday scenarios — he’ll go to war with North Korea; he’ll find take the nuclear codes and use them, et cetera — have come to pass. It is easy enough to imagine a universe in which Trump allowed himself to be surrounded by hawkish guys such as Paul Wolfowitz, or Donald Rumsfeld, or Dick Cheney. He hasn’t done that.

His unwillingness to wade into messy and unwinnable wars has in fact produced the most peaceful presidency in recent history. The US military is likewise less overwhelmed than at any point in at least two decades.

The lives of thousands of Hispanic and black American soldiers have been saved in the process. Trump’s decision to move the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem was also going to be a disaster, until it wasn’t.

All this may indeed encourage Americans to feel like they are “better off”, but what does it mean for the election?

Well, it’s worth noting also that US voters have in recent years almost always been willing to give the incumbent a second term: Clinton got two, as did Bush (the younger), as did Obama.

You know who didn’t?

Carter. Which takes us right back to where we started. He was beaten by Reagan. But he never had a number close to 56 per cent.