When the work runs out

The town of Elizabeth once prospered. Now it’s in the crosshairs of a welfare crackdown.

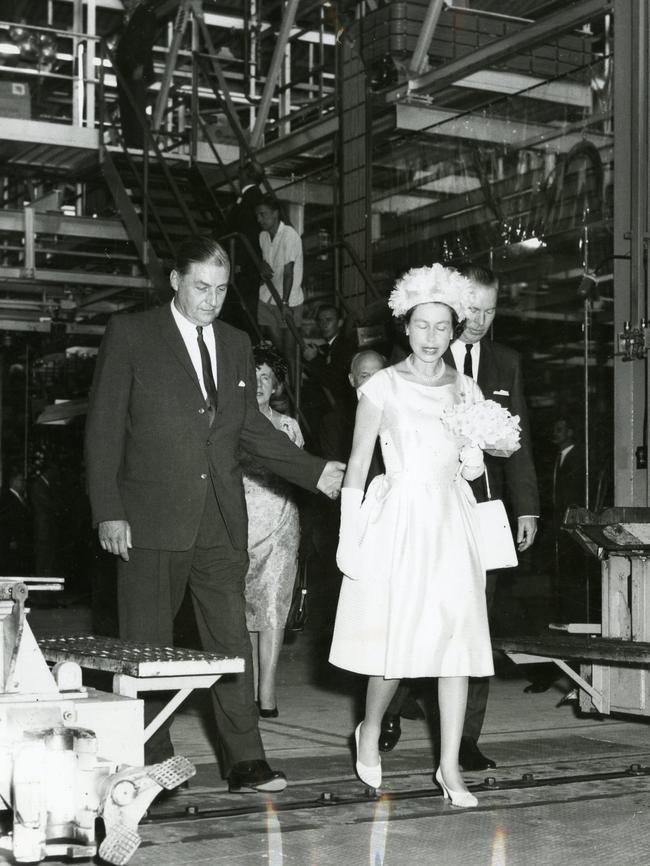

In 1963 Queen Elizabeth II visited the Adelaide suburb that bears her name, a pristine, planned satellite city that was riding the crest of a manufacturing wave and a post-war migration boom.

Hosted by Sir Thomas Playford, the Liberal premier who governed South Australia for a record 26 years and turned it into a seemingly unassailable manufacturing powerhouse, the Queen and Prince Philip toured the centrepiece of the state’s economic miracle, the General Motors Holden factory.

Faded video in the archives of the State Library of South Australia shows the Queen nodding approvingly as Holden’s newest model, the EH sedan, rolls off the line. “The Queen shows a keen interest in the display and is provided with some of the facts and figures relating to the manufacture of 600 Holdens each working day,” the plummy-voiced narrator states in the official tour video.

Holden closed almost two years ago, with 950 direct jobs lost, driving a wrecking ball through allied component industries in an area where youth unemployment exceeds 18 per cent and where, according to CommSec, the overall jobless rate is consistently in the top 10 nationwide at an average of 7.4 per cent last year.

Old dreams

You can see elements of the pristine and planned Elizabeth today. The City of Elizabeth was established by Playford in 1950 and you can still meet the people who helped make it such an early success, many of them Brits, the so-called “Ten Pound Poms” who came out after the war on cheap visas in search of quarter-acre blocks, big cheap homes, sunny skies and a land of employment opportunity.

We meet Ken and Yvonne Odenwalder outside the Elizabeth City Centre, a vast shopping mall that’s every bit as pleasant as any you would find elsewhere in Australia’s suburbs. Originally from London, Ken Odenwalder, 69, a retired bus driver, and Yvonne Odenwalder, 67, a former council clerical worker, decided to emigrate after Ken’s sister moved to SA in 1965 and bombarded them with tales from the lucky country.

“Life was bleak in London. We were really struggling,” Ken Odenwalder says. “My sister and everyone else we knew who had moved to Australia kept sending us pictures of their swimming pools, their caravans, their beach holidays, and in the end we thought, ‘Right, let’s go.’ It’s the best decision we ever made. We love Elizabeth.”

Modern malaise

It is a different story just two streets away from the shopping centre at the chaotic Centrelink office, next to the Department of Child Protection building, which is covered in razor wire, where Rebecca Nayda is wondering how she can get the hell out of the place.

Within a few minutes outside Centrelink the problems afflicting Adelaide’s northern suburbs are laid bare: drug addiction, youth unemployment, a crisis in the employability of middle-aged men, mental illness and marginal claims of disability within families that have never known work.

For these reasons, people in Elizabeth believe they are in the crosshairs for the mandatory rollout of the cashless debit card and the introduction of drug testing for Newstart and Youth Allowance recipients, as enshrined in the Morrison government’s proposed bill for a trial in three other locations: Logan in Queensland, Mandurah in Western Australia and Canterbury-Bankstown in western Sydney.

The forecourt of the Centrelink office in Langford Road is a revolving door of despair. On arrival we find two young lads skulking behind some palm trees, replete with all the tics, shakes and twitches that come with meth addiction, being frisked for drugs by local police.

A couple are drinking from a bottle of wine (at 12.15pm) and, at one point, an enraged man comes charging out of the building shouting at us from the top of his lungs.

“You should write a story about how I’ve got a cyst in the back of my neck that makes me pass out all the time and the f..king government still thinks that I should have to f..king work,” he shouts as he jumps into an old Celica and speeds off in anger.

Traneen Bugg sits in the shade with her pet dog while her partner is inside the Centrelink office resolving a payment drama. “I have had jobs before. I was a kitchen hand, and I did a lot of cleaning, but I can’t work anymore,” Bugg declares, at the grand old age of 38. “I’m going for the disability pension now because I get anxiety and depression. I get so worked up that my feet sweat and I can’t really take my shoes off at work, can I?”

A young man called Rup with limited English who is originally from Nepal and has moved down from Darwin sits on the bonnet of his car and smokes a rollie.

“I only want Newstart because I can’t get a job,” he says. “I look and look but in four months so far I find only one, as a forklift driver, but I missed out.”

Meth’s toll

Nayda tells a story that breaks your heart. She is remarkably candid in telling it, even though it isn’t remotely remarkable in Australia any more. She and her partner have just spent the best part of five years doing an absolute number on themselves through the daily consumption of crystal meth. The drug has taken a clear physical toll on her and also bent her once-loving partner out of shape. He started beating her up.

“He’s a good guy,” the tiny, thinly built 35-year-old tells Inquirer as we sit in a gutter next to a stray shopping trolley. “We never had any trouble before. I don’t blame him. He changed. It was the drugs.” Asked which drugs, she looks at me like I’m a middle-class dill.

“Ice, of course,” she says. “You know, what everyone here does.”

Because she and her partner were both addicted, she lost custody of her children, aged 14, 11, 5 and 3, six weeks ago. The loss of her kids was the shock she needed in terms of her drug use. She hasn’t touched ice since and is in the process of converting her former source of income — her child support payments — into Newstart, which is what has brought her to Centrelink on this day.

Again, she looks at me blankly when asked if she has considered looking for a job.

“I have just had my kids taken off me,” she says. “Have you got kids?”

Yes, I’ve got four too, I reply.

“Well, there you go. I’ve lost my kids. And even though I was on drugs, those kids were my world. I’m barely in the right mental state to be doing anything. I can’t function, I am lost. It’s been the hardest six weeks of my life. Those kids are everything to me. And believe me, I am a good mum. Even when I was on ice, caring for the kids was my priority. I knew I needed to get off it and I have. I am determined to get the kids back at the end of this 12 months when they’re being looked after by the DCP. It is killing me. The drug isn’t worth it. I knew that I needed to stop it.

“I just need to get out of here, out of this damned place. We need to move. It’s hard in Elizabeth. You get stuck in a cycle.”

Lost workers

As we talk freely to the drug-affected people, others brush past us and politely decline to comment. They are well-dressed, composed and presumably have found themselves between work and are drawing on welfare to stem the gap in their income. These are the people who Andrew Beer says should be shielded from ham-fisted, headline-grabbing attempts to launch some blitz on so-called bludgers.

Beer is dean of research and innovation at the University of South Australia business school, but in a former life he led a longitudinal study by Flinders University of 403 former car workers who were laid off by the now-closed Mitsubishi plant in Adelaide’s south in 2004 and 2005.

He found that half of those workers believed the job losses had affected their social life, with nearly a fifth no longer involved in formal social or group activities, and many ended up stuck in part-time or temporary work that cost them up to half their income.

Many of the workers who had exhausted all work avenues ended up on the disability pension, and those who were suffering depression or a loss of self-esteem didn’t turn to illicit drugs but alcohol.

“Some of them would just drink and drink and drink,” Beer recalls. “I’ve never seen men drink that much beer.”

As if to prove his point, outside Centrelink we meet Vlad Stamenkovic, who has been drinking from a bottle of red wine as he shares his backstory.

Stamenkovic was working as an autoplater making bumper bars before the factory went under as the car industry wound down, and then worked as a baker, but since then he has held only a few temporary jobs and is now on the DSP.

“I’m shot,” he says. “I’ve been trying to find work but there’s nothing around anyway and I’m physically past it now anyway. I’m 54 years old and I’m staying in a spare room with that guy over there who lives in a Housing Trust home.”

‘Invasion of privacy’

Despite the impact it would have on their lifestyles, every person I speak to outside Centrelink says they have no issue with cashless welfare cards if it helps people manage their money. They are less convinced about drug testing, though.

“It’s a bit of an invasion of privacy,” Nayda says. “But I want to stay off the drugs because I would do anything to get my kids back, so if there’s help provided with counselling and that, maybe it can help.”

Back near the shopping mall, office workers Nikki Rowe and Jess Philbey worry that targeting drug addicts through the welfare system could force them into crime. They also say it would simply entrench negative stereotypes about Elizabeth.

“You can go to plenty of country towns and the problem with ice is just as bad there, so I don’t know why people would single Elizabeth out,” Philbey says.

It’s a sentiment with which the Odenwalders agree.

“I hate the way people run Elizabeth down,” Yvonne Odenwalder says. “If they are going to have some kind of crackdown, it would have to be targeted.

“In one respect you don’t want people on welfare just wasting their money on things like drugs but people are doing that all over Australia. I don’t see why we should have to get such a bad rap.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout