When sport becomes a deadly pursuit

Two fatalities in less than two months have rocked the equestrian world.

For Olivia Inglis, whose surname has been synonymous with the bloodstock trade for 150 years, horse riding was something she was born to do. While she began training at the age of four, her induction into the equestrian world began long before that, having ridden “in vitro” with her mother, Charlotte.

Competing at a state level from the age of seven, Olivia went on to become one of the youngest members of the NSW Eventing Squad. Indeed, the keen equestrian was so passionate she trained before and after school each day at a specially designed cross-country course at her family’s sprawling property in the southern highlands of NSW.

At 17, she jumped up a grade to compete in the prestigious two-star category — a step before Olympic level and the mid-point in an international system that grades competitions up to the elite five-star category.

Yet at about 9.13am on the sunny morning of March 6, 2016, somewhere between the vertical jump of 8a and the oxer jump of 8b at the Scone Horse Trials in the NSW Hunter Valley, Olivia’s horse, Coriolanus — also known as Toga — clipped a jump and somersaulted over a rail. She was pronounced dead at 10.05am.

Just under seven weeks later, on April 30, Caitlyn Fischer, 19, met a similar fate when her horse, Ralphie, entered a rotational fall while competing in a one-star level. She died instantly.

As a girl growing up in Victoria’s Gippsland, Caitlyn had always loved the outdoors and asked her parents, who were then strangers to the equestrian world, for a pony after being inspired to ride by the stories she read. By 11 she was competing and at 16 she joined the Victorian Eventing Squad. A recent high-school graduate who had blitzed her final-year VCE exams, Caitlyn had been living as a working pupil at a horse stud in NSW and had planned to study advanced science at university.

Both riders had the world at their feet.

The accidents sent shockwaves through the close-knit equestrian community. There had only ever been four casualties in the sport’s history in Australia: Anna Savage, Tasha Khouzam, Rhonda Mason and Mark Myers. All occurred between 1997 and 2000.

Now, almost three years after the 2016 fatal falls, an inquiry before Deputy State Coroner Derek Lee at NSW Coroners Court has been deconstructing events to uncover exactly what happened and what can be done to ensure no repeat of such tragedies.

Trolleys heaving under the weight of a 10-volume brief of evidence were wheeled into the packed courtroom to assist the coroner in delivering recommendations to reduce the risks associated with the inherently dangerous sport. Nine issues are being investigated, including whether safety procedures at NSW equestrian events were adequate and whether the design of the courses contributed to the deaths. Other points of inquiry include whether there were appropriate risk management and emergency response plans in place and whether the recommendations arising from Equestrian Australia’s report following the deaths was “appropriate”.

“There is no doubt eventing is a challenging and dangerous sport, but one of the central issues for this court is what can be learned from Olivia and Caitlyn’s tragic deaths to try and minimise the risk of serious injury or death,” counsel assisting Peggy Dwyer explained in her opening address.

Also thrust under the spotlight has been the national body that oversees the sport, EA, which has been completely reconstituted since November. Questions have been raised about whether internal processes and divisions may have contributed to the deaths of the two outstanding riders, with the organisation burning through two chief executives, a chair and multiple directors since 2016.

Lucy Warhurst, who assumed the role of EA’s chief executive in August last year, opened the inquest with a tearful message of condolence to the parents and a promise the body was working hard to provide the safest possible environment for riders.

Charlotte Inglis, an accomplished rider herself, had been concerned about five of the jumps, including the fence her daughter fell at, from the moment she walked the course with Olivia. She was so worried she spoke with Olympian and co-course designer Shane Rose in the hour before the fatal fall. Charlotte Inglis cited issues such as the rails being skinnier than normal, an “absence of a groundline”, which indicates to the horse where to jump, and the obstacle’s similarity to show-jumping fences. A day earlier, Toga had knocked over six rails when competing with Olivia in the show-jumping event.

Dwyer told the court the jump’s construction breached five Federation Equestre Internationale guidelines, including the fact there was a downhill approach to the vertical jump, there were no groundlines, the distance between the jumps was “too long” and both parts of the fence were painted white, which makes it “more difficult” for a horse to gauge the width of an obstacle.

Renowned course designer Mike Etherington-Smith, who designed the equestrian event at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games, gave evidence he was “perfectly comfortable” with the jump in question.

But Paul Tapner, one of Australia’s most experienced equestrians, said he would have been “exceptionally unhappy” to have jumped the fence and would not have attempted it without major safety improvements.

The inquest was told the style of fence had been identified as one of the “most dangerous” of all obstacles by a British Eventing investigation following a spate of five equestrian deaths in as many months in Britain in 1999. Tapner gave evidence he suspected the jump’s designer thought the combination jump was easier than it actually was.

“I definitely feel that there would be a very high likelihood that the majority of horses would have found that 8a/8b far more difficult than (course designer) John Nicholson would have anticipated,” he said.

Three highly experienced course designers, including Etherington-Smith, unanimously agreed the jump that killed Olivia should have included collapsible technology and a “ground line”.

Australian Olympian Stuart Tinney, who competed at Scone in 2016, said while he didn’t think the course was “too difficult” for the two-star category, he wouldn’t have designed it the same way.

Another point of contention raised was the “inadequate” medical care available to Olivia when she fell. The inquest was told David Keys, the medic who assisted Olivia, was a qualified physician’s assistant but not an “advanced paramedic”, as Charlotte Inglis had expected.

“We had always been under the impression, because you could see an ambulance on site … we (thought) we had highly trained medical paramedics on site,” Inglis said.

It was revealed Keys had been hired to provide “general first aid” at the event by the now-defunct private contractor Health Services International, as EA had stopped using “highly trained paramedics” with NSW Ambulance at its events years earlier. Charlotte Inglis said Keys was faced with “a very dire situation” when he found Olivia lying unconscious “about four metres” from the back rail of the number eight jump combination. When she arrived at the scene about five minutes later, Inglis said the medic was “struggling to work his equipment” and was sitting by her daughter’s side with “a machine that needed to clear her airways”.

On identifying Olivia had sustained a collapsed lung, Keys said he felt “extremely frustrated” because there wasn’t a “long enough” cannula or an advanced airway kit on board the ambulance provided by his employer.

When questioned by Dwyer about whether he would have been able to relieve the life-threatening pressure on Olivia’s organs had he had access to the right equipment, Keys nodded.

“I was extremely frustrated,” he told the inquest. “Especially knowing how serious and how quickly it could turn bad.”

Keys revealed he had spoken with his employer about needing better equipment and teams of advanced medical professionals in the months leading up to Olivia’s fall, but had been told it was “cost prohibitive”. It was 20 minutes before a doctor, Lyndel Taylor, who happened to be riding at the event, arrived to assist.

While technical delegate Matt Bates gave evidence that Taylor had been officially engaged by Scone’s organisers to be the onsite doctor after her husband and fellow doctor, Philip Jansen, was unable to attend, she disputed this, saying there was “no way” she would have agreed to the role as she was also riding.

Instead, Taylor said she was preparing to compete when she saw a Westpac helicopter circling overhead.

After inquiring whether any riders required medical attention and upon hearing there had been a serious fall, she rushed to the scene to find Keys attempting to treat Olivia’s life-threatening injuries with an inadequate kit and malfunctioning equipment.

The president of the Scone Horse Trials, Blair Richardson, told the court he had since learned national eventing rules stipulated a “paramedic must be on site and a doctor should be”, and agreed with Dwyer that having just one medic, who wasn’t trained in advanced life support, was not “sufficient”.

Richardson said the committee at the time was not aware there were different “levels” of paramedics and had opted for HSI because it was the “preferred provider” of Eventing NSW.

EA’s rules have since been changed to stipulate an advanced life paramedic must be present and a doctor should be on site at events.

Just seven weeks later, Ailsa Carr was first on the scene when her daughter Caitlyn’s horse tripped and rolled. She told the court Caitlyn had been “bright” and focused that morning.

After watching her daughter successfully clear the first fence at the Sydney International Horse Trials, Carr told the hearing she didn’t think anything was wrong until she saw Ralphie’s leg clip the second jump. “(I saw) his back end and legs somersaulting over. Caitlyn was still in the saddle going over with him,” she said. “I saw that and the first thing I thought was, ‘I’ve got to get to her as quickly as I possibly can.’ ”

After sprinting to be by her daughter’s side, Carr knew immediately Caitlyn had died. “I looked at Caitlyn and the injuries she had and I knew she was dead,” she said. “There was nothing I could do, except to be there with her as her mother.”

On realising her daughter was gone, Carr phoned her husband, Mark. “My first words to him were that Caitlyn was dead, that she was gone,” she told the inquest.

The phone call lasted 34 seconds and ended when two first responders arrived and began to remove Caitlyn’s protective gear so they could perform CPR.

But Carr “begged” them to stop, saying: “I am a nurse, I am Caitlyn’s mother, please stop this,” she said. “She had catastrophic head injuries and I just wanted to hold her.”

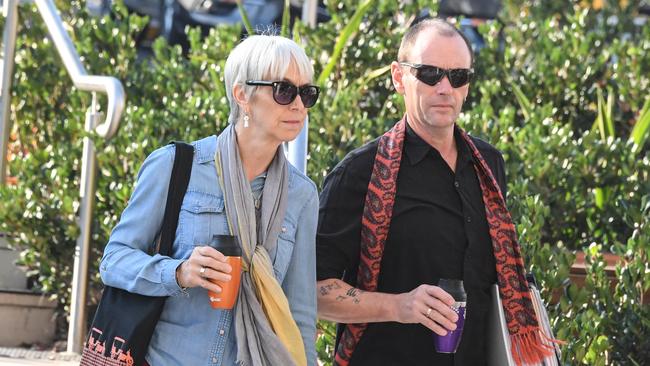

It took six minutes for an ambulance — contracted by HSI — to arrive. Outside the court, Carr and Mark Fischer told reporters they were “disturbed” to learn that seven weeks after the first tragedy, the level of medical care available to their daughter was “no different” to that provided to Olivia at Scone.

“While at Sydney we had two highly skilled doctors on site. In effect if Caitlyn had not been killed instantly they would have been in the same situation as Dr Taylor — that is, they would have been presented with a seriously injured rider, had the skills to manage the injuries, but none of the essential equipment required.”

What has also emerged is EA’s vastly different response to the two families. Carr told the court that while EA’s initial support had been “wonderful”, she was “alarmed” by EA’s subsequent investigation into the fatal fall.

As a registered nurse with previous experience in health investigations, Carr told the court she had expected an “extremely robust” process of inquiry following her daughter’s incident. “But that was not my experience of what happened with EA in relation to Caitlyn’s accident,” Carr said.

When Caitlyn’s parents later received the first draft of EA’s investigation, Carr told the court she was “alarmed” by the “many errors of fact” detailed in the document, such as the day her daughter had arrived at the competition.

Charlotte Inglis recounted a very different experience to that of Caitlyn’s mother. As a prominent member of the equestrian community, she said she had been visited many times by friends such as former EA chair Judy Fasher, and had been “very happy” with the preliminary report regarding the incident, but never received a final version.

Yesterday, in an explosive end to the first portion of the inquest, it was heard work health safety officer Samantha Farrar, who had volunteered to assist in the investigation into Olivia’s death, was advised not to pursue specific lines of inquiry regarding the jump because it was “counter-productive”.

One of the key areas of Farrar’s inquiry was to ascertain the distance between the number eight combination jump, because at the time she was convinced it was “poor striding”. But when she made inquiries about the exact measurement between the jumps, she heard disparate calculations that oscillated between 19 metres and 19.94 metres.

“It was very frustrating at the time,” she said. “I was trying to get correct data but it was very difficult to get.”

Inglis told the coroner more steps needed to be taken to improve EA’s response following a fatal incident. “They didn’t say how long these recommendations would take to put out,” Inglis said of the report. “They didn’t ever stop running events. Olivia and Caitlyn were killed and nothing changed. People were still riding.

“I think their recommendations were quite good, but there was no action plan ever included so we couldn’t see how EA was going to action anything they suggested.”

While the young riders may have come from different backgrounds, they were joined by a common thread — their shared passion for riding.

“Both were young women with enormous potential, both intellectually, personally and, of course, with the sport,” Dwyer said.

In a statement released by EA yesterday afternoon, Warhurst said Caitlyn and Olivia were greatly missed by the community.

“This Coronial process has been a challenging, confronting and emotional time for many in our equestrian community,” she wrote. “We are co-operating with the Coroner to ensure we build on the work already done in risk mitigation and improved safety for our participants. We share the determination of the Inglis and Carr/Fischer families to reduce the risk of a future serious incident or tragedy in our sport.”

The statement coincided with the announcement EA had secured extra funding from Sport Australia, which will enable it to expand the National Safety Officer from a part-time to a full-time position.

“For the first time, EA will have a dedicated safety specialist who will be available across the eight equestrian disciplines.”

Originally scheduled to run for two weeks, the inquest was extended yesterday and will return to Lidcombe in Sydney on July 23.