When politics kills the policy debate

The government is struggling to set the election agenda. Unless this is corrected Morrison’s prospects look slim.

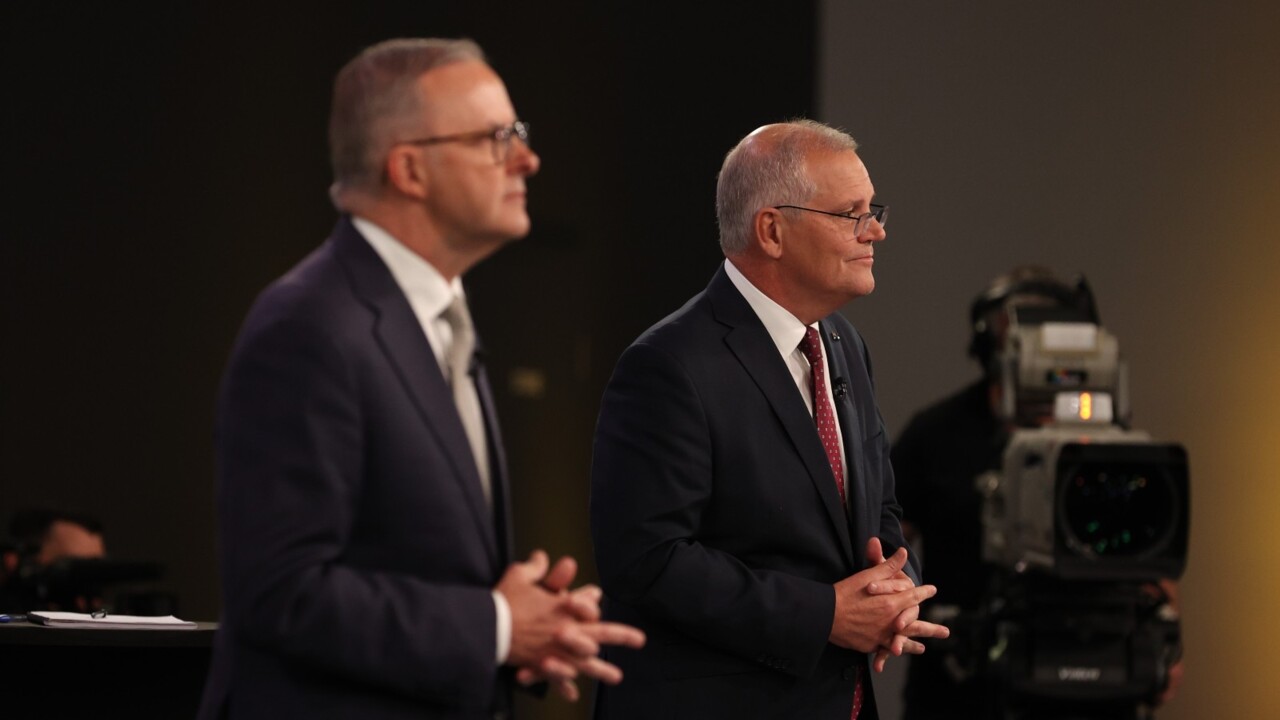

The government at the end of the second week of the campaign is struggling to set the election agenda. Unless this is corrected Morrison’s prospects look slim. This goes to Morrison’s strengths and weaknesses. They were apparent in the Sky News-Courier Mail people’s forum this week – Morrison as PM was strong on detail, policy grip and the government’s record but weak on a fresh agenda for the future.

It is doubtful whether running on economic management, job creation and the truism that only a strong economy can finance ambitious social improvements will be enough this time. Will the same miracle strike twice? The problem is accentuated by the surprise of the campaign so far – the signing of the unreleased security treaty between China and Solomon Islands – a gift for Labor that undermines one of Morrison’s main achievements: his effective stance against China’s strategic intimidation of Australia.

Newspoll this week showed the Coalition primary vote at 35 per cent, a historic low. The comparative figure at this stage of the 2019 campaign was Coalition primary support in the 38-39 per cent zone – and remember that Morrison won then by the smallest margin on voting day.

Since January the Coalition primary vote in Newspoll has been locked into the 34-36 per cent range. Morrison’s central problem is the difficulty he confronts breaking through this losing zone given his 2019 victory was delivered on a primary vote of 41.4 per cent. Indeed, looking over the last seven elections the Coalition’s primary vote, whether it won or lost, was always between 41.4 per cent and 46.7 per cent, which suggests a structural decline is at work.

While the low primary vote is a shared Liberal-Labor problem, that problem is greater for the Liberals. One Liberal MP said: “I think the people lean towards re-electing the government but lean against re-electing Morrison.”

The conundrum is that Morrison’s results in fighting a pandemic, a global recession and an assertive China engaged in coercion of Australia are world leading and stellar – yet the Prime Minister cannot command the mood of the country. None of the questions from the audience during the forum and very few questions from the travelling media concerned the economy, jobs or economic policy.

The government, in effect, runs on “more of the same” while Labor believes “more of the same” will deliver it victory. Both sides advance by prioritising negative campaigns against their opponents. This election will entrench the paradigm evident since the 2004-07 term, John Howard’s last, when the power of the negative became dominant.

It is now irresistible. This election looms as the death knell not just for economic policy reform but even for the capacity of leaders to conduct frank discussions with the public. Just weeks after a budget that increased spending over four years on the National Disability Insurance Scheme to $157.8bn from $116.1bn the previous year – a trajectory unsustainable and a program more expensive than Medicare – the debate from the people’s forum became whether Morrison lacked compassion by saying he had been “blessed” not to have children with disabilities.

Morrison decided an apology was best after being called out by Dylan Alcott for the consequences of his language when trying to be sympathetic. It symbolised the times. What worth boosting the NDIS by more than $40bn compared with a momentary lapse in sensitivity? Of course, the ephemeral, not the substance, was the media story.

Anthony Albanese, by contrast, has mastered compassion politics, the theme of our age. “The NDIS is about our humanity,” he said. “It’s a proud Labor reform and what’s happening is that people are having programs cut.” Some are – and that is distressing and painful. Yet it is a remarkable scheme with 518,668 participants last month – an astonishing 15 per cent increase in just a year, running far beyond initial estimates – and an average annualised payment of $54,400.

Declaring it intolerable that people were told colostomy bags were no longer part of their plan, Albanese reiterated the central message of his campaign – concern for people – saying Labor would be “putting people back at the centre of the NDIS”, just as he pledges to put people back “at the centre of the economy”.

Meanwhile an actuarial report to government in mid-2021 estimated the NDIS escalating to $60bn by 2030 with nearly 900,000 participants – yet there is no scope for confronting the sustainability issue in a politically acceptable fashion in this campaign. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine any future government being able to do so.

Don’t think this problem is the exception. It’s not, it’s the rule. It’s what happens when politics kills any rational framework for policy debate. The examples were everywhere this week from the NDIS, industrial relations, integrity in government and national security. The tax reform issue was lost long ago – incredibly, it cannot even be discussed. Public expectations and individual feelings shape our zeitgeist and this cultural framing is pervasive.

On Wednesday afternoon before the people’s forum, Industrial Relations Minister Michaelia Cash declared in a statement that Labor had run “another scare campaign” and she promised the government would not reform the enterprise bargaining system by changing the “better off overall” test. This seemed to correct Morrison’s earlier statement the government would revive the IR relations bill that was gutted in the parliament in 2001. Ever since, the government had run dead on the issue.

This bill is about wages and living standards. Following the consultation process set up by former minister Christian Porter, the government announced a series of modest reforms to the system, though it had to withdraw its proposal that during the pandemic business could reduce pay and conditions. In a bitter encounter most of the bill’s worthwhile measures – designed to save Labor’s system of enterprise bargaining – were gutted in the Senate by Labor and the crossbench.

These events were critical in revealing the parliamentary system could not even legislate modest advances to the bargaining model. At the time Australian Industry Group chief executive Innes Willox said: “Wages growth that has been slow and anaemic for the past five years will now stay slow and anaemic. This is going to leave workers and their employers worse off.”

With enterprise bargaining at its lowest ebb for 22 years, Business Council of Australia chief executive Jennifer Westacott said at the time: “We have condemned Australians to decades of low wages. I am just bewildered at these people who say they stand for a more diversified economy, modern manufacturing, secure work and higher wages – when what they really seem to stand for is a 1950s economy driven by protectionism, the very economy Hawke and Keating got rid of because they knew it would lead to lower living standards.”

That’s the position just affirmed this week. The government put its political foot in the water and was blasted away.

Referring to the original bill but extending his critique to the earlier revised bill, opposition industrial relations spokesman Tony Burke said: “If they get the chance to be in government again, the pay cuts will come back. They (the government) have no interest in improving wages, and given the chance they’ll cut them. When the price of everything has gone up and your pay has gone backwards, Mr Morrison now wants to cut your pay even further.”

Burke said it was Labor and the crossbench that had stopped the changes a year ago. Cash denied the government wanted to cut wages – indeed, Josh Frydenberg’s aim is to increase wages. In short, nothing has changed in the stalemate over the bargaining system.

Industrial relations was once an enduring reform mission of the Liberal Party in the cause of higher productivity-driven wage rises but that era has largely passed. Morrison was never prepared to mount a sustained political effort for IR reform and floating this in the campaign proper was never going to succeed.

Yet there has been some progress. Morrison promised if re-elected the government would legislate longer greenfields agreements for major resource projects with a value of above $500m and it would double the maximum penalty courts could apply to repeated law-breaking in the building industry, another strike against the building and construction union, the CFMEU. These are important steps – whether they would pass the parliament is another matter.

During the people’s forum Morrison was lost at sea on the issue of integrity in government. The government simply has no case and cannot find the language to mount its own view of integrity and trust. This is an extraordinary failure. The government has been damaged by the Auditor-General’s exposure of pork-barrelling and by its inability to introduce into parliament for debate its own commonwealth integrity commission or even engage in the wider integrity debate in the community.

By vacating this political field the government handed the integrity issue to the Labor Party and the independents. Even since, this cause has gained vast publicity. It is unlikely to be a vote-changer outside seats where independents are running but the damage the integrity issue has done to Morrison personally is immense.

When you don’t contest an issue, you lose. For Morrison, there are too many uncontested issues outside the economy and national security that frame him unfavourably. The upshot is Australia faces the risk of an institutional fiasco in the creation of a national anti-corruption commission if Labor wins the election and depending on its judgment.

It is hard to recall another policy debate where the apparent consensus rests on so many deluded propositions. Just consider two. First, the notion that the anti-corruption body should be designed to eliminate pork-barrelling.

This has not been a principal concern of the existing state-based bodies for the good reason that separating “acceptable” pork-barrelling from “improper” pork-barrelling only creates more problems than it solves. Pork-barrelling is as old as politics. The idea that an unelected former judge operating as an integrity commission is the answer, frankly, borders on the ludicrous.

Second, the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption model assumes the integrity commission operates as enforcement agent of the premier’s or prime minister’s code of ministerial conduct, thereby transferring enforcement of ministerial accountability from the executive and parliament to the anti-corruption commission and the media. This is a deeply flawed design. The upheavals it has caused in NSW politics will be multiplied many times if imposed on our national government. But the Morrison government, by dint of its financial flaws and political ineptitude, has given free licence to a progressive “reform” with the potential to render grave harm to our governance.

Finally, the week saw a frustrated Morrison defending his foreign policy in the Pacific and attacking Labor over its exploitation of a grievous policy failure – the China-Solomon Islands security agreement. It is early days but the agreement may become a devastating strategic setback for Australia.

It is a personal rebuff to Morrison. He would feel it deeply. Morrison has put his stamp on dealings with the Pacific leaders and cultivated his concept of the Pacific family. The hallmark of a family is trust. Morrison visited Solomon Islands as his first port of call after being re-elected in 2019. His commitment is genuine; his involvement with the Pacific goes back to his days as a young man. “We have their back and they have ours,” he said. But Solomons Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare has betrayed Morrison’s trust. He doesn’t have Morrison’s back. Australia can only renew its efforts in the Pacific, aware that most other nations do not support Sogavare and the people of his own country may not even support him.

Morrison has lashed out at Labor’s loyalty to Australia – he needs to be careful. Accusing Labor of disloyalty will only backfire.

The hurdle Scott Morrison faces in this election is a looming structural loss in the Coalition primary vote – the result of an identity crisis on the conservative side of politics that is compounded by government weakness in promoting a plan for the future.