‘When in doubt, let the evidence in’: standing up for principles of justice

Jarryd Hayne’s successful appeal underscores the need for procedural fairness, but some want to change the rules for sex assault cases.

It is too colourful to imagine the court was sending a little message to Chief Justice of the ACT Lucy McCallum about orthodox approaches to the admissibility of evidence in sexual assault cases. But it is certainly not unfair to say the NSW court demonstrated a different approach to that described by McCallum in her now famous interviews with The Canberra Times last month. The juxtaposition deserves analysis.

We will never know if an appeal court in the ACT or elsewhere would have come to a different conclusion in Hayne’s case, but we certainly need to ask whether Australia’s legal system is dividing into two (or more) systems with quite different approaches to sexual assault cases.

Do we want a country where the lottery of geography determines whether a sexual assault defendant goes to jail? Indeed, even in more traditional jurisdictions such as NSW, long-valued principles are under attack and the time has surely come to ask whether the pendulum has swung too far in some areas.

Writing the leading judgment in the Hayne case, Justice Deborah Sweeney was highly critical of the trial judge for not allowing Hayne’s counsel to cross-examine the complainant about matters that went to her credibility. Some of these matters concerned things activists now refer to as “rape myths”; for example, how a complainant behaved after the event, and to whom, how and when she complained.

Sweeney was at pains to emphasise that it was not for the trial judge to anticipate how the complainant would answer further questioning; rather, it was for the jury to have the opportunity to see how the complainant answered the questions. Sweeney found the “jury were deprived of evidence which had significance for their assessment of the honesty of the complainant”.

Sweeney’s approach seems to be “when in doubt, let it in” when considering evidence that might raise doubt as to a complainant’s truthfulness. That appears very different from McCallum’s more interventionist view when she told her local newspaper that judges have a statutory duty to disallow questions that are “offensive, annoying, harassing, humiliating or repetitive”.

In what may have been the ultimate accidental revelation, she asked the rhetorical question, “So why aren’t we doing that? Because we’re all scared of not giving an accused a fair trial.”

More than one barrister regarded that as a none-too-subtle reminder from the Chief Justice to her fellow judges, whose work she oversees, about her views on admission of evidence in sexual assault trials. It was curious that McCallum omitted to mention that the laws of evidence constrain questioning that is “unduly” offensive, harassing and so on.

Walter Sofronoff KC, who is already regarded by some in the ACT as way too fair-minded and candid for his own good, has been reported as making comments at a Rule of Law Institute dinner last week that are worth quoting: “A judge has no right to conduct a trial according to his or her own special ideas of what a fair trial looks like in order to achieve some idiosyncratic personal aim.

“A judge who seeks to conduct a trial that way is incrementally damaging the rule of law. Moreover, a judge who enters the political arena to advocate policy about how trials should be conducted generally, or in specific circumstances, is also engaging in activity that is unbecoming a judge, because a judge must remain impartial and independent. And as soon you wed yourself publicly to a policy that you advocate, you become a politician.”

There does indeed seem to be a rapidly growing campaign to increase conviction rates by restricting defendants’ rights to lead certain kinds of evidence. Calling a scenario a “rape myth” is intended to justify excluding evidence about that kind of scenario.

A fact sheet produced by the Victoria Police and the Australian Institute of Family Studies called Challenging Misconceptions About Sexual Offending says one of the myths is that many women make false allegations of rape. It says: “There is no evidence that many women make vexatious reports of sexual offences.”

That is an accurate statement. It also an irrelevant statement. There need only be some women – not many – who make false rape claims for it to become entirely reasonable to allow a defendant’s lawyer to cross-examine a complainant thoroughly, even rigorously, as to her credibility so as to avoid an innocent man ending up in jail.

Yet this sort of “rape myth” ideology has led to shocking laws and appalling injustice. It informed the drafting of the notorious section 293 of the NSW Criminal Procedure Act that rendered evidence of a complainant’s sexual experience and sexual activity inadmissible in proceedings for sexual offences. In a case called Jackmain, the NSW Court of Appeal threw out an appeal by Mr Jackmain (a pseudonym) who had been accused of sexually assaulting a woman. He had been prevented from bringing evidence at his trial of 12 occasions when the complainant made false sexual assault claims, including some instances where even the complainant admitted she had fabricated the claims.

The court held that the mandatory terms of section 293 prevented this evidence being introduced simply because it included a mention, even a false one, of previous sexual activity. The court took the opportunity to say that while the original intent of the section might have been honourable, given it was aimed at overturning a rotten culture where a complainant was questioned about previous sexual activity, the law needed to be changed to ensure a properly circumscribed exception to allow evidence of previous false allegations of rape.

Which brings us back to the motivation for all these laws. Jacqueline Maley, writing in the Nine newspapers about the Hayne decision, described what she called the “backlash emerging against the prosecution of sexual assaults” as “misogyny and outdated attitudes masquerading as concern for the principles of justice”.

She was at pains to remind us of “a glaring fact that bad faith actors will never acknowledge. That is, sexual assault has incredibly low rates of prosecution, conviction and custodial sentencing.” This means, she said, “there are either a lot of false complaints, or it means that a lot of sexual assault cases are going unpunished. Take your pick.”

Maley and others like her may see the world in black and white terms, but she omits at least one other strikingly obvious option. Namely, that while in some cases at either end of the spectrum guilt or innocence may be obvious, between those extremes most sexual assault cases are difficult, complex and often highly contested.

Recollections and understandings differ, motivations shift and the facts are unclear. The question for society is: who gets the benefit of the doubt? The traditional answer is that you can deprive a defendant of their liberty only if their guilt is proved beyond reasonable doubt. Now it seems that a new cohort of avenging angels – on and off the bench – wishes to change the old calculus.

Not only do they want to give the complainant the benefit of the doubt, they want to change the laws of evidence to make it harder for defendants to raise arguments that might create doubt in the first place. This may lift conviction rates and send some bad people to jail who otherwise may have got off. But it is a particularly ugly form of collective punishment for society to say some innocent people must also suffer to get conviction rates up. Societal pendulums often veer from one extreme to the other. But it takes fair and open-minded people – off and on the bench – to stand up to ensure the right balance is struck for the sake of justice.

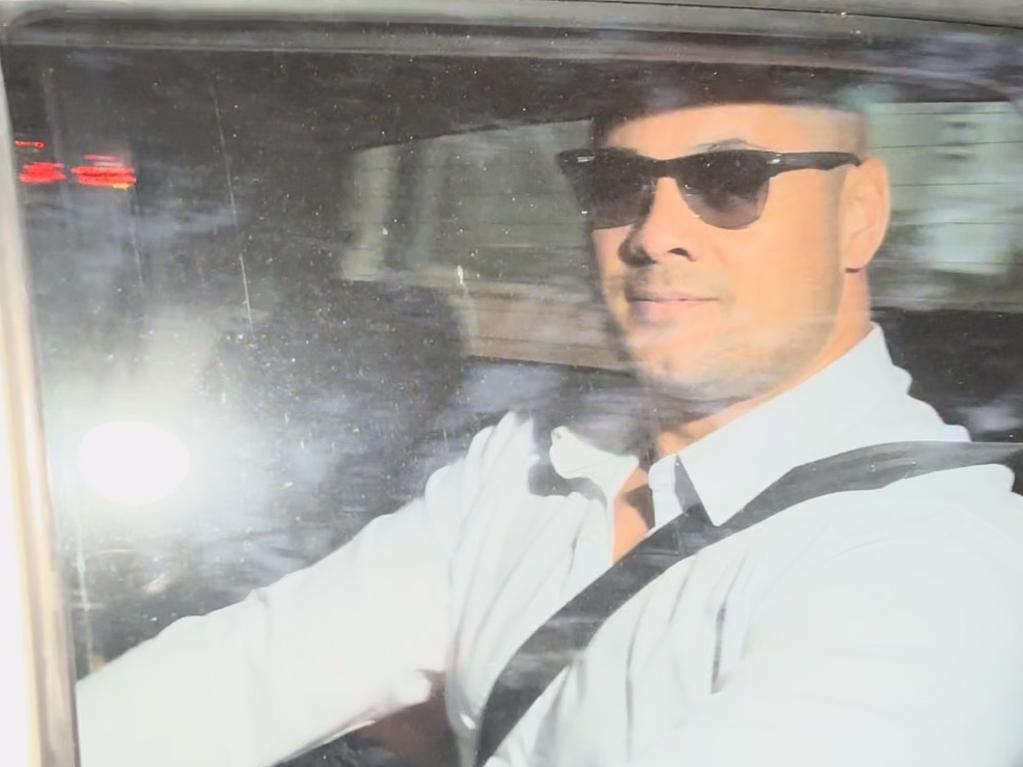

Former rugby league player Jarryd Hayne can count himself lucky he was tried in NSW and his appeal went to the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal. In a long and careful judgment that some of the more excitable commentators would do well to read, three senior NSW judges decided by majority that the failure by the trial judge to allow certain evidence to reach the jury caused a miscarriage of justice. Hayne is a free and innocent man.