What lies beneath? AUKUS subs a high reward, high risk plunge

The plan sends a a blunt generational message to China about Western commitment to the Indo-Pacific. But, beyond that, the details deserve close scrutiny.

It sends a blunt generational message to China about Western commitment to the Indo-Pacific and about the strength of the strategic bonds between Australia and its two closest allies.

But, beyond that message, the details of the plan the leaders will unveil in San Diego, California, will deserve close scrutiny and a healthy degree of scepticism.

Thanks to a series of leaks from the US and Britain, we now appear to know the basic tenets of the AUKUS announcement.

It looks like it will be a two-step process. The first step will be to purchase between three and five US Virginia-class submarines from the mid-2030s to plug a looming capability gap created by the retirement of the Collins-class submarines from 2038. The second step will be the construction of a next-generation British-designed submarine in Australia that would be completed in the 2040s and that would be used by both the Australian and British navies and possibly the US.

In the meantime, there are to be increasing rotations of US nuclear-powered submarines at HMAS Stirling in Perth to boost the US naval presence in the region.

This multi-layered plan, if it is confirmed by the leaders next week, is best described as high risk, high reward. But there are serious questions to be answered. If we make the heroic assumption that such a plan is actually realised on time and on budget, and that Australia receives all of the capability that it seeks, then it will transform Australia’s defence capability.

The acquisition of three to five Virginia-class boats, which have unlimited endurance and can fire up to 40 Tomahawk cruise missiles, would provide a much more potent submarine deterrent than the current fleet of six Collin-class conventional submarines. It would link our navy more closely than ever to the US Navy as China is rapidly expanding its own submarine forces in the Indo-Pacific.

The arrival of the US submarines in Australia in the mid to late 2030s would offset the progressive retirement of the Collins-class boats every two years from 2038. It also would relieve any inevitable schedule pressure on the second half of the AUKUS plan – the development of a common next-generation, British-designed submarine for use by both the UK and Australian navies.

Reports suggest this AUKUS submarine will be designed by Britain but probably will use a US combat system. Most likely it would be built in Adelaide and Britain, making the submarine, as Defence Minister Richard Marles says, a genuine “trilateral effort”.

This next-generation submarine would take decades to develop and build, and would not see service until the 2040s. But the lesson of history is that this AUKUS submarine plan, as sweeping as it is in its scope and ambition, appears to be based on a series of heroic and frankly unrealistic assumptions.

This is not the fault of the Nuclear-Powered Submarine Taskforce, which presented the options to the government, but rather it reflects the “moonshot” scope, as Australia’s outgoing ambassador in Washington Arthur Sinodinos puts it, of the project. So many of the projections of this colossal enterprise – the largest in Australia since Federation – are simply unknowns because they haven’t been done before in a country that has no civil nuclear industry or know-how and that has never built or operated nuclear-powered submarines, much less ones of such size and complexity. The first challenge the leaders must answer is how Australia will buy three US Virginia-class submarines (with an option for two more) to arrive in Australia from the mid-2030s. The submarines reportedly will be built in the US; however, reports by the US congress and others consistently have said that US naval shipyards are at capacity. In January a leaked letter revealed that the chairman of the Senate armed services committee, Democrat Jack Reed, and the Republican ranking member at the time, James Inhofe, wrote to Biden to express concerns that any sale or transfer of Virginia-class submarines to Australia would undermine the US Navy’s own requirements.

The only obvious solution to create space for the timely build of Australian Virginia-class boats in the US would be for Australia to fund a third submarine production line in addition to the two the US already has. This would be an expensive task. Yet if Australia does fund a third production line in the US for Virginia-class boats, why wouldn’t Australia simply continue the production of Virginia boats until it has eight of them, rather than seek to build a completely different next-generation British-design submarine in Adelaide?

Clearly one class of nuclear-powered submarine is easier and cheaper to operate and maintain than two classes of submarines. Eight Virginia-class Australian submarines would be a very powerful deterrent to China. New Virginia-class submarines would have a life expectancy of about at least 30 years, meaning they still will be in their prime when Australia builds a completely different British-designed submarine in Adelaide.

Could it be that the tail is wagging the dog here and that the need to feed work to Britain under AUKUS and the perceived need to build submarines in Adelaide are the motivators for the expensive and complicated decision to run two classes of nuclear-powered submarines? The government needs to explain clearly why it has chosen two different classes rather than one.

Another key question the government must answer is how Australia grows and trains enough people with nuclear know-how to maintain, sustain and crew the large Virginia-class boats when they eventually arrive in the mid to late 2030s and then the AUKUS submarine after that.

A University of NSW study this week found that Australia must train at least 108 PhD-level researchers in nuclear engineering every year to operate and maintain its future nuclear-powered submarines. In addition, Australia would need 2635 “mid-tier” nuclear professionals and 3010 “nuclear-aware” workers. At present the nation’s only nuclear engineering program at UNSW has 53 postgraduates and 74 undergraduates.

Vice-Admiral Jonathan Mead, the chief of the Nuclear Powered Submarine Taskforce, says he has 20 Australians overseas studying nuclear science or nuclear engineering, with plans for 30 more next year. This new workforce would be required for both the Virginia-class boats and the next-generation AUKUS submarine.

On current projections, Australia won’t be able to meet its targets in time for the arrival of the US submarines. On top of this, Australia will have to turbocharge its ability to produce crew members who have the nuclear training required to crew a nuclear-powered submarine. To give some idea of the timelines needed, Mead says Australia needs to set 14-year-old schoolchildren on the path to becoming captain of the first nuclear-powered submarine.

Quite apart from the qualifications is the sheer number of crew members who will be required. The Virginia-class boats have a crew of 135 compared with only about 48 for a Collins-class boat. The future AUKUS submarine is likely to be the next-generation version of Britain’s Astute-class boat, which has a crew of almost 100. The navy has traditionally had difficulty finding enough crew for its six much smaller Collins-class boats, not least because of the better-paid alternatives for engineers in the mining industry.

The government will need to announce a raft of new courses or even institutions to help train the personnel needed to maintain, sustain and crew the two types of nuclear-powered submarines Australia will acquire. The reality is that the crews of the initial Virginia-class submarines will have to be majority American, presumably sailing, somewhat bizarrely, under an Australian flag.

Marles is sensitive to the claim that Australia is ceding part of its sovereignty through joint collaboration, common submarines and joint crews. He maintains Australia would always have control over their use regardless of the level of integration with the US or Britain.

“Whether our defence assets are developed indigenously, acquired from abroad or developed in partnership, Australia will always make sovereign, independent decisions as to how they are employed,” he says.

Even so, it will be a strange sight to see Australian navy submarines that are built in the US and captained by Americans. There are also key questions for the government to answer about the next-generation submarine to be built in Australia. Reports suggest the new boat is most likely to be a version of the yet-to-be-designed British successor to the Astute, known as SSN(R).

The latest speculation suggests this new AUKUS boat will consist of a British-made hull and a US combat system, with most or all of the boat to be built in Adelaide. If so, this would mean Australia and Britain would operate the same submarine in the future with a possible larger variant being constructed for the US.

Such a decision would be a seismic shift for Britain, which has never allowed a US combat system into its submarines, preferring to have homemade British systems instead. Australia needs to have a US combat system for its submarines to give interoperability with the US fleet in the Pacific. The critical point is that Australia needs any future submarine to be the same as that used by Britain or the US, and preferably both.

For Australia to choose a British-designed submarine and then have to – alone – incorporate a US combat system would be a disaster. Australia is uniquely bad at incorporating foreign systems into its submarines and ships. Almost every shipbuilding project in Australia’s history has foundered on this issue and it would mean Australia’s new AUKUS submarine is an orphan used only by Australia. So this next-generation, British-designed submarine makes sense for Australia only if it is identical to that being operated by the UK.

Then there is the question of cost. Previous estimates of the size of eight nuclear-powered submarines ranged from $100bn to $171bn, but these estimates were made on the assumption that only one type of nuclear-powered submarine would be chosen. If the government chooses two types then it will surely cost more for Australian taxpayers than would just one type of submarine. Cost estimates for such enormous projects are always rubbery at best, so we should be sceptical of whatever figure the government delivers on this. Costs always go up, never down.

But with another range of expensive defence procurements expected in the forthcoming Defence Strategic Review next month, the government will need to explain exactly how the country is to pay for the two classes of nuclear-powered submarines and what other non-defence spending may need to be sacrificed for it.

Next week we will see in full what the AUKUS submarine proposal is. But from what has been leaked already, the proposal raises more questions than answers.

The government will need to find some convincing arguments to allay any perception that it has chosen a complicated, high-risk and overly expensive solution to Australia’s submarine dilemma.

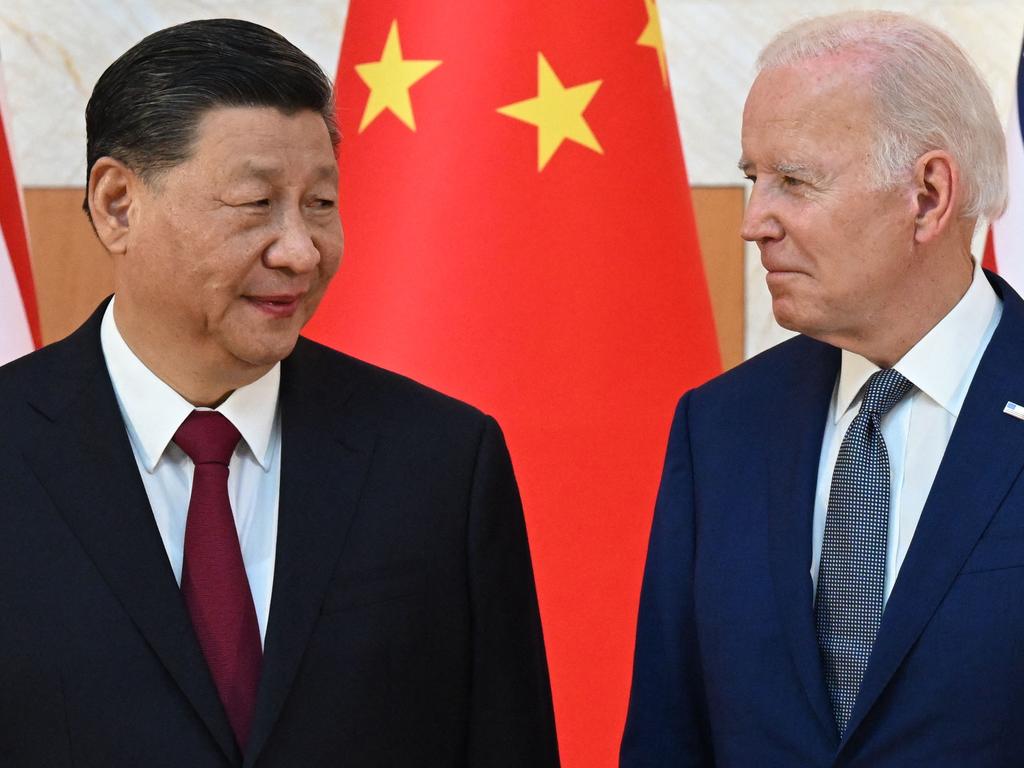

When Anthony Albanese, US President Joe Biden and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak unveil the AUKUS plan for Australia’s new nuclear-powered submarines next week, their most important message will be one of political intent. For all three leaders, especially a US president, to come together to make such an announcement speaks volumes about the depth of support in the US and Britain to help Australia acquire such a potent capability.