I suppose you must start with some basic questions. Is there a unique Australian way of life? If so, what is it? And ultimately, why is it essential? Is it worth investing in?

Well, the first question is easy. Yes. Anyone of us; all of us lucky to have spent time living or travelling overseas know that Australia does have its own identity, its own unique culture and a specific way of life.

Let me start with identity, which is a bit easier, and move on to way of life later on.

If we just take the two countries we are seen as culturally closest to, America and the United Kingdom, we can see clear differences.

Having grown up and lived in the US, in the UK and in Australia, I appreciate our historical bonds and the similarities of our character. But I also know and appreciate what makes Australia different.

Our Constitution, for instance, is a melding of the Westminster system and the American federation, the best of the old world and of the new.

All three nations value freedom, democracy, aspiration and endeavour – qualities we have fought hard to protect. And while we differ in national character, there are similarities there too.

The ironic Australian sense of humour can be traced to Britain and Ireland, while our nation was forged with a frontier attitude, reminiscent of the US drive westwards, with strong veins of optimism and self-reliance.

But as America expanded west, their explorers and pioneers found rich plains, vast rivers and mountains; we found a far harsher and more difficult environment. Perhaps this added to our sense of irony; it certainly added to our enduring resilience.

When my father delivered his first Boyer lecture nearly 13 years ago, he referenced a favourite Russell Drysdale painting that to him represents the beauty, character and resilience of the Australian landscape and its people.

The painting, The Stockman and His Family, depicts an Aboriginal family, clearly burdened by the hardships of the past, weathered by the harshness of their environment, but with eyes cast hopefully to the future.

Without ignoring issues of Indigenous disadvantage, my father was focusing on the shared characteristics and experiences of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians – isolated from the rest of the world, tested by the vicissitudes of our climate, and together carving out a future on our continent. Drawing inspiration from the strength in that image, my father said, “Our national character should never lose that steeliness.”

Steeliness: it is a good word, isn’t it? It’s a better quality, one that Australians have displayed handily throughout the past.

That my father warned, or implored us not to lose that quality, tacitly acknowledges that we could. It is understood that national identity and culture is, rightly, a constantly evolving, always living thing. It is always a work in progress.

Identity is like a long rope, made up of hundreds of woven strands of shorter individual fibres. In totality the woven strands provide strength and purpose, and a kind of collective unity. But as one strand ends, others are woven in. That’s what gives a rope its strength. But the strands at the beginning of the rope are entirely different from the strands at the end.

We are not who we were 100 years ago, or who we might become 100 years from now. Culture and identity are not, and cannot be, frozen in time. It is this fluid aspect of identity that makes the Centre for the Australian Way of Life such an inspired idea.

Understanding first what characteristics make us unique and what shared values unite us is essential before we can celebrate the good, reject the bad and, yes, embrace the new.

This endeavour works only if you believe, as I do, that together we are incredibly lucky to be Australian. That our country, while not perfect, represents invaluable freedoms and characteristics that are worth celebrating, nourishing and defending.

I am always saddened when elements of our citizenry, often the elites who have benefited most from our country, display not a love of our values but a disdain for them.

This is why some of what sets Australia apart is under threat. Our core values, our successes and even our history are under constant attack.

Nourishing and defending those core values are extremely important. Not to do so has real world, real bad outcomes.

This past month we have all been both horrified by the brutality of Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine and inspired by its leaders and its people in their courageous defence of their country. The people of Ukraine were living in an emerging democracy, embracing their post-Soviet sovereignty, working hard to achieve their economic and political aspirations, when Russia decided to snatch that future away from them.

Ukrainians also know that their country is not perfect, and yet tonight they continue to fight and to die for their sovereignty, their identity and their most basic of freedoms.

It is heart-wrenching to watch, and we must continue to help them defend themselves. Most of us agree on this basic point.

And so I was shocked when a respected poll in the United States last week revealed that barely a majority of Americans would defend their country if invaded in a similar way. Could it really be that the America that fought not just a bloody war of independence from a foreign empire but also an even bloodier and more nationally defining civil war of emancipation not long after; could it be that this exceptional country is now so politically divided that barely half of its citizens care deeply enough for its values that they would fight for them?

The damage done to the American psyche through unrelenting attacks on its core values and via the destructive rewriting of its history is very real.

It has been widely reported that Russia’s attempts to influence recent American elections were designed to sow anger and discord on all sides. There were, and presumably remain, efforts to divide the country and undermine its faith in its core values and institutions.

The Russians found fertile ground. In 2019 The New York Times published the first of a series of essays called the 1619 Project, which recast American exceptionalism as racist from inception.

You couldn’t have picked a more polarising and dividing thesis. The essays, criticised by many historians, are what they profess to be in their title: a project to recast American history and long accepted values through a radical and radically divisive lens.

Its author, Nikole Hannah-Jones, has said that “all journalism is activism”. That’s wrong. And it has done great damage. America is a great country, populated by an amazing and also resilient people. It will overcome these challenges.

But here, in Australia, let’s learn from this cautionary tale.

Let me go back to one of my original questions. Why is our identity and our culture so important? Why is it worth investing so much in?

By definition an Australian identity must apply to all of us. It is something that is not political, or economic, not drawn by class or education, not based in race or sex, or whether you are a new immigrant or a member of our oldest peoples. An Australian identity unites all of us.

Together we are strong. Divided we are weak.

But our national identity and culture are weathering constant attempts to recast Australia as something it isn’t.

To listen to our national broadcaster or much of the media elite is to hear about a uniquely racist, selfish, slavish and monochromatic country.

The reality could not be more different – we are one of the most tolerant, generous, independent and multicultural countries in human history. Not without fault, but without peer.

How can we expect people to defend the values, interests and sovereignty of this nation if we teach our children only our faults and none of our virtues?

We must arm our young people with the facts and not undermine them with false ideological narratives.

Australians have an innate concept of fairness.

We have a visceral sense of what we call a “fair go”. This is our own idea, an antipodean concept, a deeply rooted understanding that whatever our circumstances, we deserve the same opportunities, the same respect, the same fair go.

It is why we welcome immigrants, embrace aspiration and scoff at class-based deference.

Former Labor prime minister Bob Hawke wrote of a national character that “adapted a class-ridden tradition to produce in this vast continent a people with a cocky insouciance, a society where mateship and the concept of a ‘fair go’ were more than myths”.

Similarly, at Gallipoli on Anzac Day in 2000, then Liberal prime minister John Howard spoke of sacrifices to defend a country where “prosperity and opportunity are derived not by birth but by endeavour”.

There is a rugged optimism about us, too, an attitude embodied in the phrase “She’ll be right”.

This is not a line of resignation, or near enough being good enough; it is a unique Australian combination of optimism and stoicism. “Stoic optimism.” Steeliness.

In a fraught world we need to draw on our characteristic strengths to protect ourselves and our future. What is confronting, though, is when our way of life is challenged from the most trusted and even benign of sources.

One year ago, who would have believed that in Australia a pregnant mother would be arrested for questioning a government lockdown?

Who would have thought daily press conferences where citizens were scolded and told to dob in their neighbours would become must-watch viewing?

Surrendering personal liberties, accepting government interventions and absorbing record financial hardships were literally unquestionable burdens, at risk of fines or imprisonment.

All done in the blink of an eye, with few checks and balances, and we are still counting the costs.

Alcoholism, domestic abuse, suicide – all saw record spikes during the pandemic. Why did we accept this? It must never happen again. Australia did well to turn the tyranny of distance into a temporary pandemic advantage, using maritime borders and hotel quarantine as a moat against the virus, until vaccines were developed.

The federal JobKeeper scheme provided a financial lifeline that kept employees linked to their workplaces.

Our spirit of mateship shone through at street level, with people checking on the welfare of neighbours and supporting local businesses, and it was reflected in the innovation of an informal national cabinet.

Yet we became a victim of our own success, with state leaders thinking they could out-do each other with lockdowns and remain Covid-free forever.

The popularity of these approaches no doubt was fuelled by the alarmist language and fearmongering of politicians and much of the media.

But it is the media’s job to question these policies. To examine their consequences. And to ultimately hold our elected officials to account.

That’s our job.

Lockdowns and border closures kept families apart, children were denied face-to-face education, businesses were crushed, non-Covid health issues such as cancer screenings were delayed, and mental wellbeing was jeopardised.

Tweed Heads and Coolangatta were divided like Cold War Berlin; Australian citizens were stranded overseas, banned from coming home; and those at home were not allowed to leave.

But much of the media bought into this. News Limited titles nationally campaigned for our readers to get vaccinated. It was extraordinarily and importantly impactful. But when any columnist questioned the efficacy or fairness of vaccine mandates, they were labelled anti-vaxxers. Decades ago, George Orwell pointed out how language is not only shaped by politics but is used to fabricate new realities. Debates around virus treatments, mask effectiveness, the human and economic costs of lockdowns, and vaccine mandates were treated as taboo by many elements of politics and the media.

Debate is essential to democracy. Important issues need to be aired, examined and judged. It can be uncomfortable, but it is the media’s key role in our system. Hoeing to one orthodoxy does not allow this; and is not the media’s role.

We must always be wary of the suppression of information. The contemporary thrill to “cancel” someone whose opinion you do not share is just the latest insidious form of censorship.

Infamously, YouTube banned Sky News Australia based on YouTube’s own judgments and changing standards about a handful of pandemic-related videos. Initially, YouTube justified this censorship by stating “YouTube does not allow for content that denies the existence of Covid-19”.

OK. But when challenged they could not find a single instance of Sky ever denying the existence of Covid-19, so they had to pivot quickly and shift their justifications. The PR executives took over and they said this: “YouTube does not allow medical disinformation about Covid-19 that poses a serious health risk or harm, or that is in contradiction with local and global health authorities guidelines.”

Apart from being an obvious and blunt cudgel to Australian’s freedom of speech, this standard was impossible to adhere to.

Which health guidelines do you use? YouTube says local and global guidelines.

YouTube used the World Health Organisation as its fact-checking guide; a body that was late to declare the pandemic, quick to admonish Australia for closing its international border, changeable in its medical rulings and reluctant to pursue the origins of the virus.

And our local guidelines were not much better. Every state had different rules, apparently different “science”, and they changed them constantly.

In America today states with strong mask mandates have just lifted them, claiming “the science has changed”. Well, no, it’s an election year and the politics have changed. What YouTube and the other members of the tech censor class are doing, at least when dealing with the media, is not protecting viewers from dangerous views or opinions but rather ensuring that only the current orthodox view is allowed.

Unfortunately for them, these orthodox views often turn out to be wrong.

Last year, quite early in the pandemic, Facebook banned any posts suggesting Covid-19 might have emerged from the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

In September HarperCollins publishedWhat Really Happened in Wuhan by The Australian’s Sharri Markson, pulling together all the threads of this story, which she had reported in The Australian and on Sky News, in a brave and open quest for the truth.

This has been another great Australian characteristic: impertinence in the face of convention or authority. This nation has been at the forefront of demanding to know the truth about the pandemic’s origins.

Had Sharri not written such a compelling and well-sourced book, would the tech companies and media elites eventually have come around and published the facts themselves? Presumably only when they could no longer justify hiding obvious truths. But that is not brave. That is not journalism.

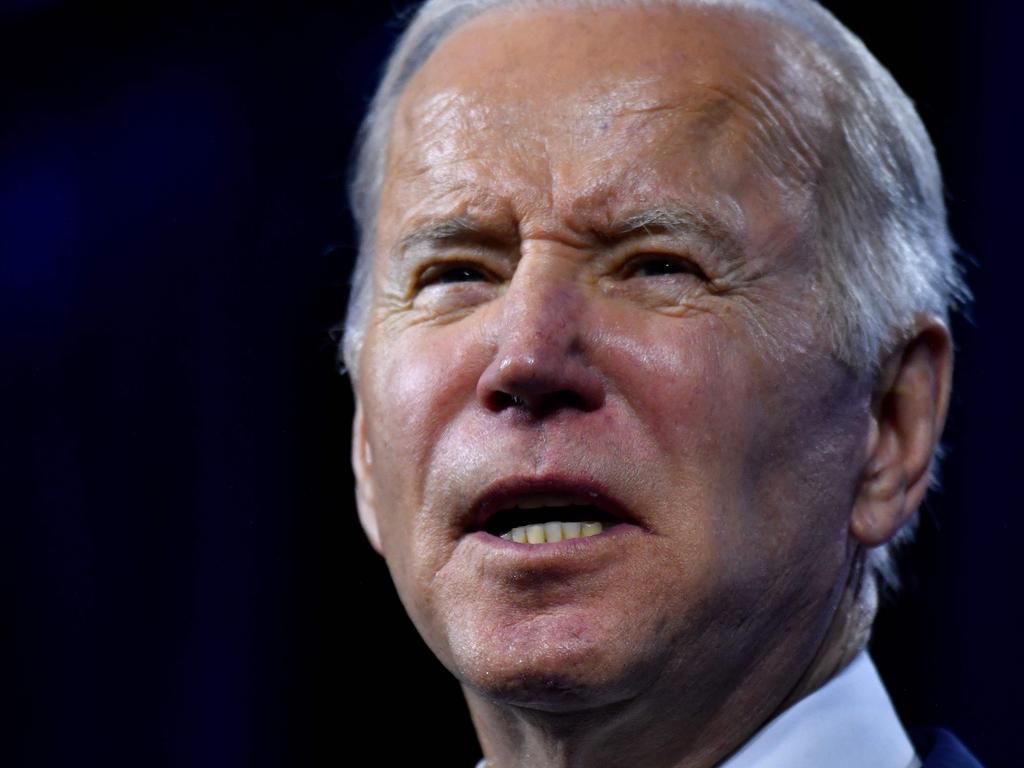

Leading into the US presidential election, the tech companies, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and practically all the media suppressed the discovery of Hunter Biden’s laptop. While much of the contents of the laptop was salacious, many emails and other documents raised pertinent and serious questions about the Biden family’s foreign ties and lobbying.

Had the laptop belonged to another candidate’s son, it would certainly have been the only story you would have heard in the final weeks of the election.

But lies were concocted: “The laptop was hacked or stolen”; it was not. Or: “It was Russian disinformation”; it was not. And the story was completely suppressed. It was censored by everyone.

Fast forward to last week. The election is over. And The New York Times, quietly, in paragraph 24 of a story about Hunter Biden’s taxes, admits that it has now “authenticated” the laptop and its contents.

All the New York Post’s reporting was true. All was factual. But it was suppressed and lied about for as long as it suited the political orthodoxy. This, from purely a journalistic point of view, is shameful. It should not happen. And we should never let it happen here.

Finding truth is often hard. It very often comes with great personal costs. But it is essential to our nation and to our future. Telling the truth is part of our national character.

In Australia we should reject every effort, and there are many, to limit points of view, to obstruct a diversity of opinions and to enforce a singular world view. Those efforts are fundamentally anti-Australian.

The flip side of this is that we should celebrate debate, unite behind a wide diversity of opinion, and vigorously protect the basic freedoms that as Australians we have enjoyed for generations.

Which brings me back to our way of life. An Australian way of life is something that by definition must allow us to be Australian. It can’t be that our way of life would disallow any of the traits that make up our unique Australian identity.

Rather, the unifying characteristics that make us Australian must be allowed to flourish under our way of life. That is why freedom is not only a core value of our way of life, it is essential to it.

As Australians we are free to practise our “rugged optimism”; we are free to be “authentic”, free to be “egalitarian” and free to aspire to a “fair go”.

We are free to practise our religions, and be Christian, or Muslim, or Hindu. We are free to be gay, or straight, or trans. We are free to make our own health choices about our own bodies. We are free to travel and to explore.

As Australians we are free to have our own opinions. Free to be Labor or Liberal. We are free to be left and we are free to be right. We are free to disagree. We are free to choose what we read and what we watch. We are free to make our own minds up about things.

These freedoms are unifying. And such freedom is at the core of who we are. If you need more proof, look no further than our updated national anthem. It’s right there in the second line: “For we are one and free”.

But we cannot take our unity or our freedoms for granted. We cannot be complacent. We must defend our Australian freedoms from erosion.

The Covid-19 lockdowns and “emergency health orders” took many of these freedoms away. As the pandemic becomes endemic let’s learn from the past two years. Did we give too much freedom up? Was it worth it? And let’s make sure we get all the rights back we thought we had.

Essential to this is our freedom of speech. Our freedom to question authority and to hold our leaders to account.

We should be wary of those who would deny this freedom and call for less debate, less openness, and less diversity of opinion. Instead, we should together celebrate, indulge and defend all the Aussie freedoms we cherish.

Lachlan Murdoch is co-chairman of News Corporation. This is a speech given to launch the Centre for the Australian Way of Life at the Institute of Public Affairs on Tuesday.

Our way of life has faced some serious challenges over the past year. For a long time, for many of us, it changed. And so this discussion is as pertinent as it is important.