Vote on Indigenous voice to parliament deserves to lose, badly

The question is whether parliament in practice will be able to stand up to this new body. Odds on it won’t.

I am an Australian constitutional law professor who is against the voice. My take is that you could count on one machine operator’s hand the number of other constitutional law professors in this country who would also be against amending our Constitution in this way, certainly publicly so.

I think that is in part a function of the collapse in viewpoint diversity in academe – the relentless demand for “diversity” is focused on reproductive organs and skin pigmentation, not on outlooks, and certainly not on the search for a few conservative ones. But leave that for another day. Let me tell you why I think this constitutional proposal is a bad idea and why I also believe it will lose.

To start, it’s worth a quick reminder of what happened in my native Canada before Pierre Trudeau amended and repatriated the Constitution there in 1982, attaching a powerful bill of rights. Many were worried this would emaciate the elected parliament and that the judges would have too great a sway. To get it through, proponents therefore put in s. 33, a “notwithstanding” clause. This gave parliament the power to override the judges on most rights-related matters. Put bluntly, the legal and constitutional position became that the last word stayed with parliament.

Know what? As soon as this constitutional change happened, many of those pushing for the change, who’d conceded the s. 33 override, started screaming blue murder at the mere prospect of the elected parliament ever using it. In the 40 years since this constitutional change, want to guess how many times s. 33 has been invoked by the national parliament to gainsay the judges? The answer rhymes with the fifth Roman emperor, the pyromaniac.

In practice, it is completely unusable. The left-wing parties don’t want to use it and the conservatives cave in to the public broadcaster and universities and civil servants and lack the cojones to use it. Not even conservative Stephen Harper did, though he mooted it on occasion. Again, many of those who conceded the legal provision later ensured it was practically unusable after the amendment was in place.

Returning to Australia, when proponents of the voice like Greg Craven point to how, legally and constitutionally, the last word will remain with parliament, that may have been correct with 1950s-type judges, but who knows today? And anyway, that’s not all voters need to bear in mind. In real-life terms, the question is whether parliament in practice will be able to stand up to this new body, the voice. I’m betting not.

The analogous evidence from Canada is clear. And Anthony Albanese has already said it will be a brave parliament that gainsays this body. If you agree with that empirical take, then that’s what voting Yes means, regardless of the technical legal position and your view of today’s judges. You’re betting on whether future Coalition governments will be invertebrates or not, and I know what my money is on.

Here’s another big problem. Our top judges, even without a bill of rights, have in my view indulged in some big-ticket judicial activism in the past few decades and done so in the name of the Constitution. Two years ago, in the Love case, on the question of whether a non-citizen person claiming Aboriginal status could be deported, the majority High Court justices used concepts such as “otherness”, “deeper truths”, “connections (to Australia that) are spiritual and metaphysical” and more of the same to claim that judge-made law that purported to speak in the name of the Constitution now recognises “that Indigenous peoples can and do possess certain rights and duties that are not possessed by, and cannot be possessed by non-Indigenous peoples of Australia” and that “different considerations apply … to … a person of Aboriginal descent”.

They did that with our present Constitution that gives them nothing to work with. Will putting something like the voice into our Constitution make judicial adventurism easier or harder?

There are other problems on top of those. We currently have no real detail at all. The Prime Minister calls this a minimalist model, but in fact it is maximalist – we are to give maximum trust to the politicians to devise something after the fact. These are the same politicians who imposed the world’s toughest lockdowns and blew out the budget. They’re offering a “no details until afterwards” package. And right now both houses of parliament are effectively controlled by Labor and the Greens.

Then there is the unalterable fact this proposal is thoroughly illiberal. It affords different rights to different Australian citizens due solely to unalterable characteristics they were born with.

Right now, all Australians are given the same voting and other rights. Aborigines are over-represented in the current parliament. With the voice in place some Australians will have more say than others locked in. That’s based on a sort of “let’s fix past differential treatment with future differential treatment” rationale. There’s not a lot of empirical evidence that’s a good idea.

We can also cast an eye across the Tasman to New Zealand and see how race-based policies and initiatives are working there. Are they bringing citizens together or driving them apart? And do such initiatives resolve matters or just lead to more demands?

Of course it would be nice to see Peter Dutton emerge from wherever he is and oppose the voice on principle, or on any of the grounds above. But whether he does or not, I welcome the coming referendum. I think it gives ordinary citizens a say, and it will lose. In fact, I think it will lose badly. It certainly deserves to do so.

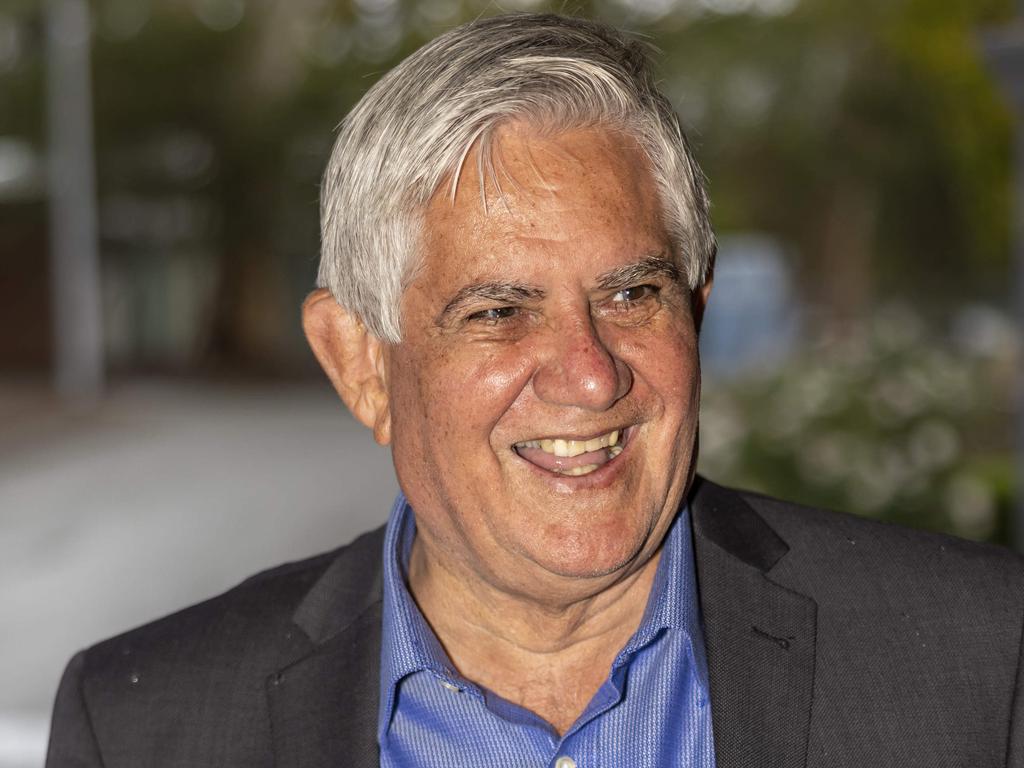

James Allan is the Garrick professor of law at the University of Queensland.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout