Victorious First Fleet won Australia’s ‘Trafalgar Day’

January 26 marks the date when Arthur Phillip outfoxed the French.

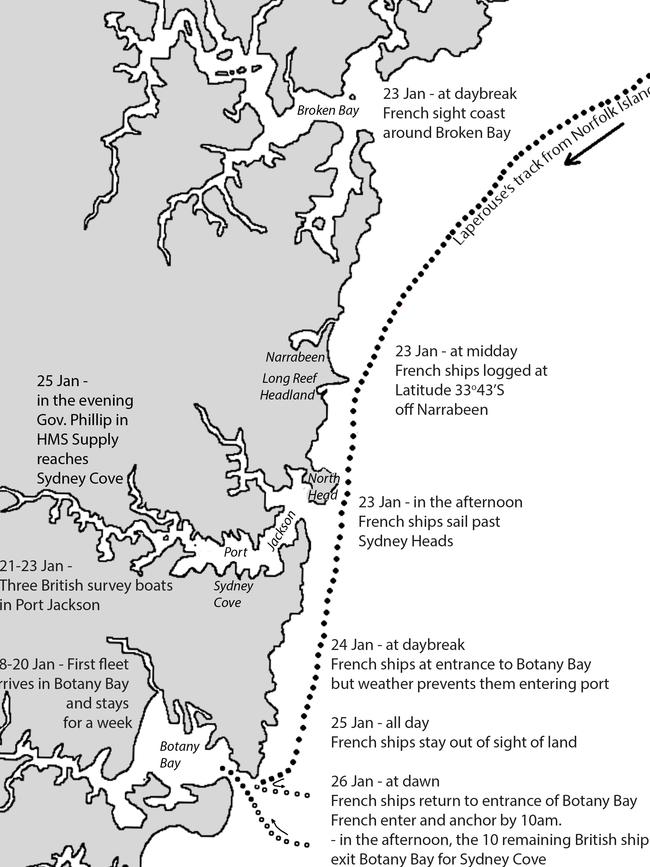

At daybreak on Saturday January 26, 1788, two French frigates – La Boussole and l’Astrolabe – stood at the entrance of Botany Bay. Their commander, Rear Admiral Laperouse, gave the signal to enter. He was following new instructions that he had received four months earlier in Kamchatka, Russia.

They were written by Louis XVI after learning that Britain was sending an occupation force to New Holland (Australia). The ministers at Versailles hoped to forestall the English and sent a dispatch across Siberia to Kamchatka, ordering their French navigator to sail straight for Botany Bay.

Laperouse arrived on the coast near Broken Bay at dawn on Wednesday January 23. His target, Botany Bay, lay 30 miles to the south and, in between, was Port Jackson. By midday, the French ships were level with Narrabeen Lagoon. By mid-afternoon they were outside Sydney Heads. If Laperouse had seized the opportunity and turned to starboard, he would have discovered “the finest harbour in the world”. But Laperouse stuck to his instructions and continued south to Botany Bay

Laperouse had no idea whether the British fleet had reached Australia. Nor did he know that Botany Bay was not Arthur Phillip’s true destination.

Eighteen years earlier, Captain James Cook had anchored HMB Endeavour in Botany Bay, but he was unimpressed with the shallow inlet. With a couple of trusted men, he followed an ancient track north along the coastal ridge. From its highest point, Cook saw below him Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour). Here was a naval paradise: a natural deepwater harbour and defensible port with ample room to manoeuvre.

As a naval officer and marine surveyor, Cook knew this strategic gem had to be concealed until Britain could garrison the place. He reported it to the Admiralty as soon as he arrived back in London. Indeed, evidence of Cook’s verbal report is held in the Home Office archives. Meanwhile, however, the vast extent of the harbour was omitted from Cook’s published journal and charts.

When Arthur Phillip was given command of the First Fleet, he was told that Port Jackson was his true destination, but he would not sail there directly. Its entrance had never been sounded and Phillip could not risk taking 1500 souls onto a hidden sandbar. Instead, the fleet would rendezvous in Botany Bay (where the poor convicts remained locked in the holds) while a quick survey was made of Port Jackson.

The first ship of the fleet arrived in Botany Bay at 2.15pm on Friday January 18. This was HMS Supply with Phillip on board.

After anchoring on the north side of the bay, Phillip was rowed ashore where he met representatives of the Gameygal people.

The next day, three more ships arrived: Alexander, Scarborough and Friendship. On Sunday, HMS Sirius arrived with the remaining vessels – Charlotte, Lady Penrhyn, Prince of Wales, Borrowdale, Fishburn and Golden Grove.

Remarkably, all 11 ships had reached Botany Bay within 40 hours of each other.

At daybreak the next morning, Phillip took three small boats round to Port Jackson to sound and survey it. They spent that first night at Camp Cove and the second at Sydney Cove. Here, at the narrowest point of the harbour, they found a reliable stream of water. The site was ideal for the new settlement. They set off back down the harbour, eager to collect the fleet and bring it round to Sydney Cove.

As the three small English boats sailed out through the heads, they should have bumped into the two large French ships heading south from Narrabeen. It was a photo finish. Yet, extraordinarily, neither party saw the other on that Wednesday afternoon.

On Thursday at daybreak, the 11 British ships were ready to leave for Port Jackson, but the weather had turned foul. Worse still, when the Englishmen peered through the fog, they saw two foreign vessels at the entrance to Botany Bay.

Phillip guessed that these were Laperouse’s ships. Before leaving London, Phillip had asked the Admiralty for instructions as to what he should do if Laperouse beat him to Australia. But now Phillip’s sole objective was to secure Port Jackson for Britain. Protocol could wait.

This day – Thursday January 24 – marked day one of the three-day Battle of Port Jackson. The apparent imbalance between the two sides is chimeric. If 750 furious convicts broke out of the ships’ holds and joined forces with 200 armed Frenchmen, the Pacific’s new European colony would likely be French, not British.

For now, the bad weather favoured the British. The French ships were unable to enter Botany Bay, so they stood out to sea for safety. They disappeared for the rest of Thursday and the whole of Friday. Some crewmen thought they had gone north to Port Jackson. Phillip hoped they hadn’t.

Meanwhile, Phillip postponed his departure and ordered the English colours to be hoisted at Sutherland Point. He forbade anyone to board the French ships or reveal that they were going to Port Jackson. He reassigned some marines and convicts to different ships and prepared for departure the next morning.

By Friday the gales were worse, making it almost impossible to get out of the bay. But Phillip was determined that he, at least, would reach Sydney Cove before nightfall. Eventually, when the ebb tide came at noon, HMS Supply got out and started up the coast. She struggled against the current, battling giant swells and a fierce thunderstorm. Eventually, she passed through Sydney Heads and into the harbour as flashes of lightning lit up the shores. No French ships were seen as they came to anchor in Sydney Cove at 7pm. Now Phillip’s chief concern was the safe arrival of the remaining 10 ships, which he’d left with his second-in-command Captain John Hunter of HMS Sirius.

On Saturday January 26, Hunter woke to find the fog had disappeared and the wind had dropped. At 6am when he gave the signal to weigh anchor, he saw no reason why the entire convoy would not be safely anchored in Sydney Cove by early afternoon. But the return of fine weather served both parties. As the sun rose, the two French ships were seen at the entrance to the bay. Laperouse may not have beaten the English to Botany Bay, but his government still wanted a detailed report of the new British settlement there.

This was a blow for Hunter. Laperouse’s arrival in Botany Bay would seriously delay his departure because of protocol demands. Both Hunter and Laperouse lowered a boat and sent an officer to each other to exchange greetings. The formalities over, the French ships steered a path through the 10 exiting British ships and came to anchor near the beach where the HMS Supply had spent the previous week.

These courtesies cost Hunter at least four hours, which he could ill afford if he was to get his nine lumbering merchant ships anchored in Sydney Cove before sunset. He signalled the masters to stay in formation and follow the plan they had agreed the previous evening.

But as the heavy vessels approached the narrow entrance, the light winds made it difficult to navigate. Vessels were thrown out of their order and collisions were inevitable as they tried to avoid each other and the rocks. Amid the noise and panic, Prince of Wales ran into Friendship, carrying away her jib boom, while her new mainsail and main topmast staysail were torn to pieces by Friendship’s yard. Being in imminent danger of running onto the rocks, Charlotte suddenly swung into the path of Friendship. There was a tremendous smash, destroying the woodwork on Charlotte’s stern.

The French watched on dumbfounded as the British ships raced for the exit. Laperouse recorded that the English lieutenant who greeted them “appeared to make a great mystery of Commodore Phillip’s plan”.

By 1pm, Sirius was out, but Hunter could not leave until all the ships were free. Two hours later, the last of the vessels cleared Cape Banks and the convoy made its way up the coast.

Up at Sydney Cove, Phillip was waiting anxiously. With the better weather, he had expected the convoy to arrive soon after midday. Now he feared the worst – that the French had interrupted the British campaign.

Then around 5pm, the workers on shore erupted with cheers when the bow of Sirius nosed into sight around the eastern headland, soon to be named Bennelong Point. By evening the whole convoy was anchored inside Sydney Cove, except Sirius. She was moored out in the stream where the officer on watch could spot any French vessel approaching up the harbour.

As the sun dipped below the horizon, it was time to celebrate a safe arrival and a glorious victory. Lanterns on the ships illuminated the snug inlet, cheering sailors manned the yards, while officers and civilian staff came ashore to join the others around the flagstaff. This was an occasion for thanksgiving after a successful voyage and for celebrating a great naval triumph.

Three weeks later, when the portable “Government House” was finally erected, Governor Phillip invited Laperouse to visit. The French commander and three friends travelled from Botany Bay on horses provided by their host. On February 20, Governor Phillip and Rear Admiral Laperouse met at Sydney Cove. As Laperouse gazed out over Sydney Harbour, he realised the damage to the English ships had been a small price to pay for them to. Britain had won the Battle of Port Jackson without firing a shot.

After two nights of partying, the Frenchmen returned to Botany Bay. Their six-week visit to Australia ended on March 10, when they sailed out of Botany Bay to continue their voyage – and vanished without trace.

Almost 40 years passed before scattered wreckage was found on Vanikoro in the Solomon Islands, northwest of Fiji.

Margaret Cameron-Ash is the author of Lying for the Admiralty: Captain Cook’s Endeavour Voyage and Beating France to Botany Bay: The Race to Found Australia. Out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout