Victoria’s incompetence could not be more stark

Belgium, the worst performing nation (after San Marino), has had 350 times more than Singapore, one of the best. Even within Australia, Victoria has recorded 19 times more deaths than NSW.

The usual explanations for differences in outcomes are unpersuasive. Gender cannot explain the success of many male leaders; authoritarianism cannot tell us why many democracies, including South Korea and Taiwan, did well; nor can accusations about the pitfalls of populism explain the mediocre outcomes of centrist Emmanuel Macron in France.

Other factors — from healthcare spending to population, urbanisation, and gross domestic product — also fail to correlate with pandemic success. Something else is going on.

The prescription for handling novel infectious diseases is not rocket science: border measures and extensive testing and tracing, advise hand washing and social distancing, cancel large events, stockpile personal protective equipment, and expand hospital capacity.

Whether countries took these steps ultimately came down to the underrated question of competence. A University of Munich study concluded that “government effectiveness is significantly associated with decreased death rates”, after controlling for various factors including population age, health system capacity and government policy response.

This is often called “state capacity”: the ability to effectively decide and implement good policy. State capacity is no easy task. Governments often lack skills, resources and knowledge. This leads to persistent and widespread policy failure.

Last year was the year of state capacity. Government competence became the difference between life and death, freedom and tyranny. The initial state failures and cover-up in Wuhan, China, led to an outbreak of a new infectious disease.

On the other side of the ledger, many Asian countries, scarred by previous diseases, successfully contained outbreaks. Then, hundreds of thousands died in some of the wealthiest countries across Europe and the US.

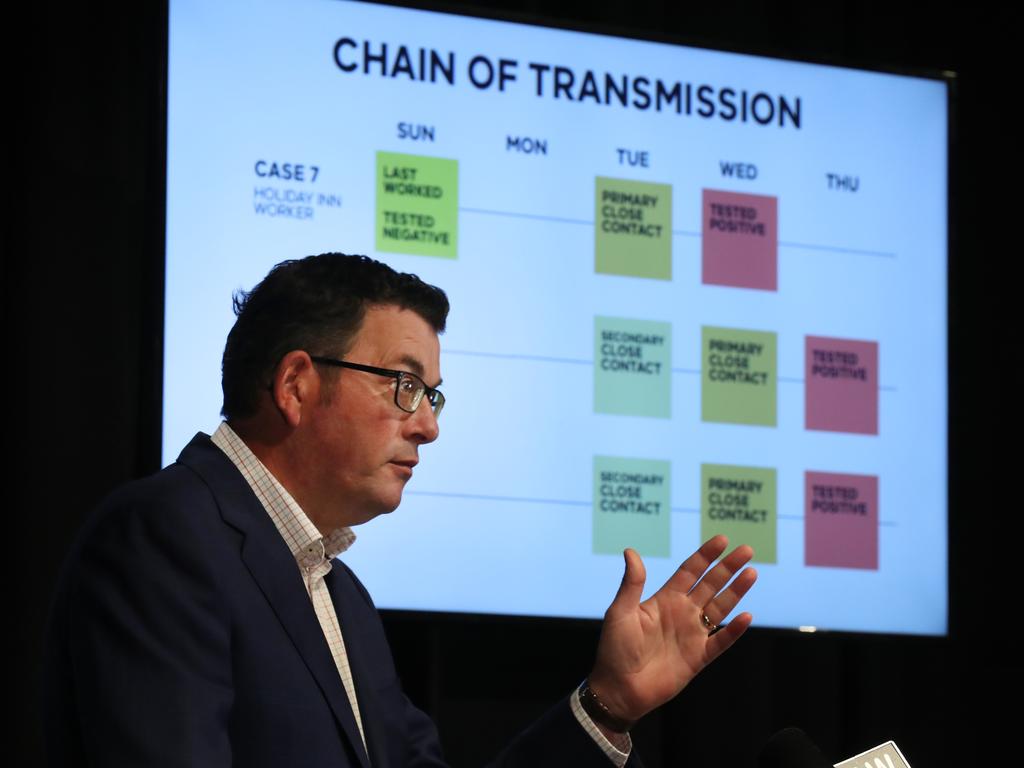

In Australia, all states and territories appeared to be on a similar buoyant trajectory, helped by early national border measures. Then, cascading governance failures created the exception that shows Australia is not simply the Lucky Country. Victoria’s lacklustre infection control in hotel quarantine seeded a new outbreak into the community. Then inept contact tracing failed to catch cases in time. Melbourne consequently had one of the most prolonged lockdowns in the world.

Contact tracing is a perfect test of state capacity. It is time sensitive, requires data sharing and cross-agency co-ordination, rapid training and substantial community trust and knowledge. Success means the avoidance of lockdowns: a telltale sign of state failure is shutting down businesses and severely restricting freedoms because you cannot prevent a disease outbreak.

Victoria’s contact tracing system used pens, paper and fax machines. It was too slow: contacts waited up to nearly two weeks to be notified about a potential exposure. The tracing was operated centrally, in contrast to NSW or South Korea, which use decentralised local area health districts with expansive local knowledge. The result is striking: between June and October last year, only 3 per cent of NSW cases had an unknown origin, compared with 22 per cent in Victoria.

Hotel quarantine and contact tracing is just the tip of the iceberg of Victoria’s lacklustre governance. During lockdown, for instance, Victoria required the manual printing and hand signing of forms for work travel permits.

By contrast, in NSW citizens could use Service NSW to apply for a digital border crossing permit. Officials worked overnight to ensure the system was in place in time. This was possible only because of a longer-term investment in state capacity by the NSW government. Service NSW was established in 2013 to improve customer service using modern technology. It brought together dispersed functions, thousands of phone numbers and hundreds of websites into a one-stop shop accessible online, by phone or at more than 100 retail fronts. It was an entirely new agency whose leadership and frontline largely came from private sector customer service roles.

Service NSW provides more than 1200 transactions, from a new digital drivers’ licence to public transport card top-up, tools to ease cost of living such as energy switching, and check-in for COVID-19 venue contact tracing. It even provides a free, dedicated business concierge to guide entrepreneurs through applying for licences to start a business.

Service NSW could save the state billions by digitising transactions that previously required expensive manual processing. But, most important, it saves citizens time and hassle. Calls are picked up within minutes by real humans, not machines like previously. Service NSW has a satisfaction rating of more than 95 per cent, up from NSW’s 66 per cent customer satisfaction before the project.

The contrast with Victoria could not be starker. The Victorian government announced Service Victoria in 2015, though it was not established until 2018. There is no single call centre or shopfronts, and the website often just links to other government pages. Service Victoria has already had difficulties: a solar rebate “public beta” had a 40 per cent failure rate for facial identification — which is meant to be one of the main features of Service Victoria. Under the Kennett government in the 1990s, Victoria led the way in reforming service delivery by decentralising and empowering local control. It has fallen dramatically behind.

Good governance coupled with useful technologies does not just make lives easier, save taxpayer money, and help business creation; it has much bigger implications for the future of our institutions. The pandemic has taken a battering ram to the legitimacy of many Western governments. Bloomberg’s John Micklethwait and The Economist’s Adrian Wooldridge have called it a wake-up call for the West: “If we respond to the COVID crisis intelligently, treating it not just as a public-health disaster but a stress test of Western government, if we take government seriously as Asia does, we can preserve the Western advantage.”

If we ignore the crisis, a China-dominated world beckons, they claim. The few hundred years’ experiment in government by the people, for the people, is little more than a tiny speck in history. If it is to endure, it must effectively serve the people.

There is much work to be done. Service Victoria is a joke, Services Australia is still in development and even the most successful, Services NSW, is just a beginning. There needs to be big investments in talent, skills and technology, as well as new ways of thinking about how the state operates.

The late and sorely missed Paul Shetler, founding head of the Digital Transformation Agency, which is responsible for improving service delivery using technology, was scathing about self-obsessed government agencies.

“Nobody wants to engage with government,” Shetler warned. “Nobody cares about the DTO, ATO, DHS, DSS — the whole alphabet soup — nobody cares about any of that. Nobody really wants to engage with it because people just want to get stuff done.”

Services should be delivered at people’s fingertips, in a personalised, integrated and streamlined manner, across levels of government and departments.

Shetler pushed back against opposition from bureaucrats and ministers in silos protecting their turf. “Ministers tend to be captured by the departments they are the minister for and sometimes that causes problems,” he warned.

The hierarchal and cautious public service model captured by Max Weber, designed for 19th-century challenges when the state was substantially smaller and the technology we have today unimaginable, is not suited for our era. There is a need for an agile, iterative and experimental approach — along with some acceptance of failure.

In the past many who advocated for smaller government gave up on the technocratic task of improving state capacity. In 1964, Republican US presidential candidate Barry Goldwater declared: “I have little interest in streamlining government or in making it more efficient, for I mean to reduce its size.” (Goldwater won only six states.)

Indeed, Western governments have too many programs, costing too much and delivering too little. By contrast, Singapore spends among the least on health yet has among the longest life expectancy and lowest infant mortality. It also spends less on education yet comes out at the top of league tables by emphasising excellence and firing incompetent teachers.

Small is beautiful. But it is foolish to entirely abandon improving the state. Despite allegations of decades of “neoliberal” policies, the state has not shrunk and withered away. It continues to take up almost one-third of the economy and does a multitude of tasks such as delivering infrastructure, defence, transport, education and healthcare. We, the taxpayers and users of services, have a very strong interest in the best possible bang for our buck. The goal should be to shrink, focus and improve the state.

Governing is a challenging task: the scale is massive, antiquated systems are hardwired and politics is constantly changing. Reform is a radical exercise that takes political will to push back against bureaucratic inertia and entrenched interests. The windfalls are colossal: reducing costs for taxpayers, making lives easier for citizens, and saving people and businesses countless hours of bureaucratic wrangling.

We have learnt the hard way this year that state capacity really does matter. It is simply too important to ignore.

Matthew Lesh is an adjunct fellow at the Institute of Public Affairs and the head of research at the Adam Smith Institute. This is an edited extract of a research essay published in The IPA Review.

COVID-19 has been a dramatic test of governments across the globe. A once-in-a-century plague descended more or less simultaneously, challenging the ability of states to protect their citizens. Success has been mixed: Britain has had over 35 times more deaths per capita than Australia; the US has had almost 50 times more than South Korea.