US military build-up in Australia hailed as major win for security

Australia is being transformed into a pivotal American military base – the likes of which we have not seen since World War II.

This historic change has occurred so progressively over the past decade that few Australians have stopped to consider the big picture significance of this moment for Australia’s future security in the face of a rising China.

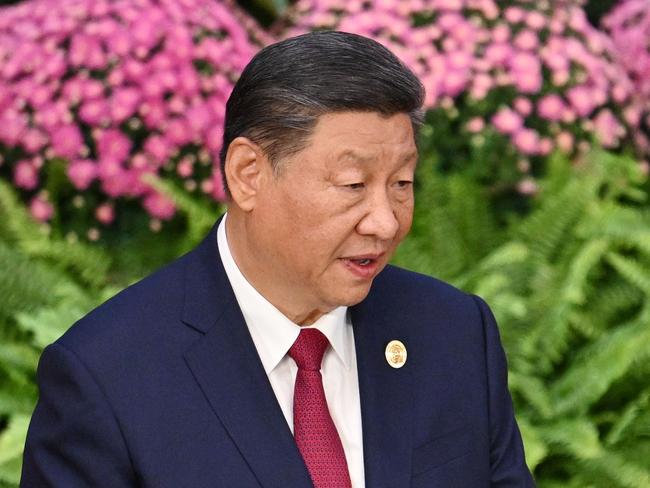

If Chinese President Xi Jinping wants to see the self-harm he has inflicted from his country’s hegemonic behaviour in the Indo-Pacific he needs to look no further than this new and powerful military marriage of convenience between Australia and the US.

As a direct result of Xi’s actions, Washington now sees Australia as its last regional bastion in any future conflict with China. This is a pivotal and historic change from the Cold War when the US saw Australia as only a bit player in its larger battle with the Soviet Union.

This has severely complicated China’s calculations about its long-term ability to project power far beyond its shores, and is likely to give it pause when considering military adventurism in the region, including against the likely flashpoints of Taiwan and the Philippines.

As a result of China’s rise, the US is now moving fast to position its military here on a scale not seen since US general Douglas MacArthur plotted from Brisbane in 1942 to repel the Japanese advance in the Pacific.

This ever-increasing rotational presence of US forces – from marines, to nuclear bombers to warships and soon nuclear submarines and much more – has not just been welcomed by both sides of politics in Canberra and in Washington, it is being turbocharged.

“We now have the largest concentration of US forces here since World War II, and it has been absolutely critical to our security given China’s rise,” says Professor Peter Dean, a principal author of the recent 2023 Defence Strategic Review.

“Even at the height of the Cold War we weren’t really contemplating the basing or rotating of US combat forces through here,” says Mike Pezzullo, author of the 2009 Defence White Paper. “It’s a radical change and it is transformative.”

Pezzullo says Washington’s thinking about the newfound strategic importance of Australia was expressed in stunningly blunt terms last month by the chair of the US House of Representatives’ powerful foreign affairs committee, Michael McCaul, who said Australia had become “the central base of operations” for America’s military to deter Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific.

“It is the central base of the Indo-Pacific to counter the threat,” McCaul said. “If you really look at the concentric circles emanating from Darwin – that is the base of operations, and the rotating (US) forces there are providing the projection of power and force that we’re seeing in the region.”

Paul Dibb, the architect of Australian defence policy, describes the growing US presence here as a “dramatic” moment in Australia’s military history. “It is something that in the past wasn’t considered necessary – but that has changed because of the sharp deterioration in our security environment,” he says.

It says something about the Australian public’s suspicion of China, with Beijing’s record military spending and its bully boy behaviour in the South China Sea and the South Pacific, that this historic upgrading of Australia’s most important alliance has occurred with little public debate and even less protest.

While there are occasional anti-US voices that question the wisdom of this new military marriage, such as former prime minister Paul Keating, former foreign minister Bob Carr and the Greens, these are mostly voices in the wilderness that are out of kilter with the views of most Australians today. They carry little or no weight with either of the major political parties or with the vast majority of defence experts.

What’s more, unlike during the Cold War, when Midnight Oil wrote anti-US anthems like US Forces and peace protesters blocked the gates of the joint bases like Pine Gap, there is no longer any peace movement to speak of. As we saw in Melbourne this week, what passes as today’s peace movement has been hijacked by anti-Israel protesters and a ragtag bunch of Marxist and socialist groups whose main gripe is Gaza, not the presence of US forces.

It seems that few Australians want to man the barricades these days to protest against American forces. In part this is because there is little public sympathy or support for the rise of China but there is also less anti-Americanism here than there was after the disastrous Vietnam War and Iraq conflicts. The peace protest movement is more fixated these days on supporting the Palestinian cause in Gaza than worrying about US marines in Darwin or US nuclear subs in Perth.

A poll released last week by Sydney University’s US Studies Centre found 72 per cent of Australians believe the US alliance either makes Australia more secure or the same, compared with just 16 per cent who thought it makes us less secure. And 48 per cent of Australians believe China is more harmful than helpful in Asia compared with just 18 per cent who believe it is more helpful.

“If you go back and look at polls in around 2013, most people thought of China as an economic partner rather than as a security threat,” says Dean, who is also a director at the USSC. “But that has been completely reversed in the public’s mind because of the behaviour of Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party in our region.

“People have seen how China militarised the South China Sea, launched a trade war against us, tried to undermine Taiwan, and how it keeps making bellicose and bullying threats.”

Dean says people are willing to tolerate US forces on Australian soil in a way they did not previously because the stakes for Australia’s security are now so much higher.

“In the 1970s and ’80s we were not under any significant risk, other than if the Cold War went nuclear,” he says. “Now the stakes are completely different. They are so much higher and people get this. That’s why the public’s faith in the US alliance has not taken the hit that it sometimes took in the past.”

Former defence minister Kim Beazley says many in the peace movement have little time for China. “They don’t like what happens internally in China, they don’t like what happens with the Uighurs; there is not a sentiment out there that wants to speak up for China.”

This lack of public opposition explains why the growing US military presence in Australia has enjoyed bipartisan support.

The Labor government, which has traditionally been more wary of a US military presence in Australia than the Liberal Party, has embraced the trend.

“American force posture now in Australia involves every domain: land, air, sea, cyber and space,” Defence Minister Richard Marles said after he approved the deployment of more US bombers, fighter jets and spy planes to Australia at last month’s annual AUSMIN ministerial talks in Washington.

The US military build-up in Australia has grown over the past decade in tandem with China’s military build-up in the region coupled with its record levels of military spending.

The revamped US presence began in 2011 when then president Barack Obama signed the Forces Posture Initiatives agreement allowing for the rotation of 200 US marines through Darwin in the dry season. This annual rotation has since grown to more than 2500 marines and has been augmented by regular rotations of nuclear-capable B-52 bombers at RAAF Tindal air base near Katherine. The US forces to rotate through northern Australia have expanded to include US army landing craft, fighter jets and maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft.

Work continues on enhancing a ring of military bases spanning the coastline from Perth to Townsville to make them available to US forces in a conflict.

A major logistics depot for use by US forces has been set up in Albury-Wodonga and will eventually be established in Queensland, and both countries will jointly produce guided weapons in Australia.

Most significantly, US nuclear submarines will now regularly visit HMAS Stirling in Perth ahead of a permanent rotation of US submarines there from 2027.

The US is also driving the initial phase of the AUKUS pact by pledging to provide between three and five of its Virginia-class submarines to the navy from the early 2030s.

The reason the US now prefers to station military equipment in Australia rather than at forward bases such as Guam is due to the rapid development of China’s land-based anti-ship missiles and its fast-expanding “blue water” navy.

Australia is a safe haven for US forces beyond the range of an initial Chinese attack, but close enough to the region to act as a springboard into any regional conflict.

“It is the growing ability of China to project power with its long-range missiles, long-range submarines and long-range ships which has made northern Australia come into focus (for Americans) because geography becomes important,” says Pezzullo.

He adds that Australia would still be a “strategic backwater” for the US if China had not developed such long-range offensive weapons capable of hitting Guam and other US bases in the region.

“The Americans now see Australia’s geography as fundamentally crucial,” says Dibb. “If push comes to shove with China, they know they know they have the capacity to project power from the relative safety of this untouchable continent.”

The rise of the Chinese threat and the increasing reliance on the US has led some critics to claim Australia has abandoned its oft-quoted pursuit in the 1980s and ’90s for more defence “self-reliance”.

But Beazley, who in many ways was the father of the quest for self-reliance, says the strategy of self-reliance outlined in his seminal 1987 Defence White Paper was always linked to Australia’s alliances.

“It was never just self-reliance,” he says. “It was self-reliance within the framework of our alliances and a recognition that we would always be a requirement to keep intact our relationship with the US.

“What has changed over the long term has been the rise of China. Now the focal point of the international system for the Americans is the Indo-Pacific. And so Australia has gone from being the periphery (in importance to the US) to the essential core.”

But as the rapid build-up of US military assets in Australia continues, the government still needs to work out the full implications of this major change.

Some have questioned whether the positioning of so many American military assets here could in any way complicate sovereign decision-making for Australia in the case of regional conflicts involving China, especially in relation to Taiwan.

The government insists that AUKUS and the greater presence of US forces in Australia would have no impact on its ability to make sovereign decisions about how it deploys Australia’s military.

In a recent speech, former Labor foreign minister Gareth Evans argued that the growing integration of US and Australian forces, especially Australia’s acquisition of American Virginia-class submarines, will undermine Australia’s ability to make sovereign decisions about whether to join a regional conflict involving the US.

“The notion that we will retain any kind of sovereign agency in determining how all these assets are used, should serious tensions erupt, is a joke in bad taste,” Evans said.

Former prime minister Keating has gone one step further, saying the AUKUS submarine pact would make Australia the “51st state” of the US.

“They are easy words to throw out but they are not backed by any reality,” says the USSC’s Dean about the claims made by Keating and Evans.

“What they are claiming is an elaborate conspiracy theory. They are asking people to ignore the statements of their own government about us having sovereign control of those capabilities. They are saying there are special secret conditions on the use of this equipment.

“If that is the case then there are dozens of politicians in the three AUKUS countries and thousands of officials all undertaking a vast conspiracy to delude the public of three continents.

“Paul Keating, Bob Carr and Gareth Evans are asking us to believe that the Prime Minister is lying about this and that there is a conspiracy to delude the Australian people.

“They have zero evidence for these claims,” says Dean.

Beazley believes there is no risk to Australia’s ability to make sovereign decisions about its military with AUKUS or the presence of more US forces in Australia.

“We are no more compromised on sovereignty than we were in the 1980s when we had joint facilities like Pine Gap,” he says, pointing out that those facilities provide critical military intelligence for both Australia and the US.

Pezzullo says that a better way to express the issue is that we are seeing a “pooling of sovereignty” with the increasing enmeshing of the military forces of both countries: “Alliances and commitments to mutual defence assistance require a pooling of sovereignty rather than a compromise of sovereignty. When you talk about compromises of sovereignty you’ve got to tally up what compromises to sovereignty would occur if we were under the influence of a power whose values, interests and sense of self was very different to us.”

Pezzullo says that pooled sovereignty within an alliance is often more attractive than going it alone and cites the example of Sweden and Finland which, in the face of a perceived enhanced threat from Russia after its invasion of Ukraine, broke with decades of neutrality and joined NATO.

The government is sensitive about accusations that it has undermined its sovereignty by going all in with America.

It still avoids the use of the term “bases” when describing the presence of American forces in Australia, preferring instead to use the word “rotations”.

This is technically true in that US forces come and go and most importantly they operate from Australian military bases that are under Australian command. This gives Australia sovereign control over the manner of their use.

But the reality is that whatever word is used to describe the phenomenon, there are now increasing and ever larger US forces in the country at any one time.

In the end, the increased presence of US forces in Australia is something to be celebrated because it is “essential”, says Dibb.

“This is an essential trend that recognises that with an ambitious China on the prowl, we are much more vulnerable in a way than we were not with the Soviet Union.”

Beazley says simply that there are “no negatives” in America increasingly using Australia as a base to station its forces against China.

“We will have a very powerful deterrent force here,” he says.

“I mean, we are talking about our security, and every bit of it makes us better.”

Australia is being transformed into a pivotal American military base the likes of which we have not seen since World War II.