US general David Petraeus opens up about the risks of nuclear war

Retired four-star general David Petraeus is guarded about the risks of nuclear conflict over Ukraine, but warns against taking Vladimir Putin lightly.

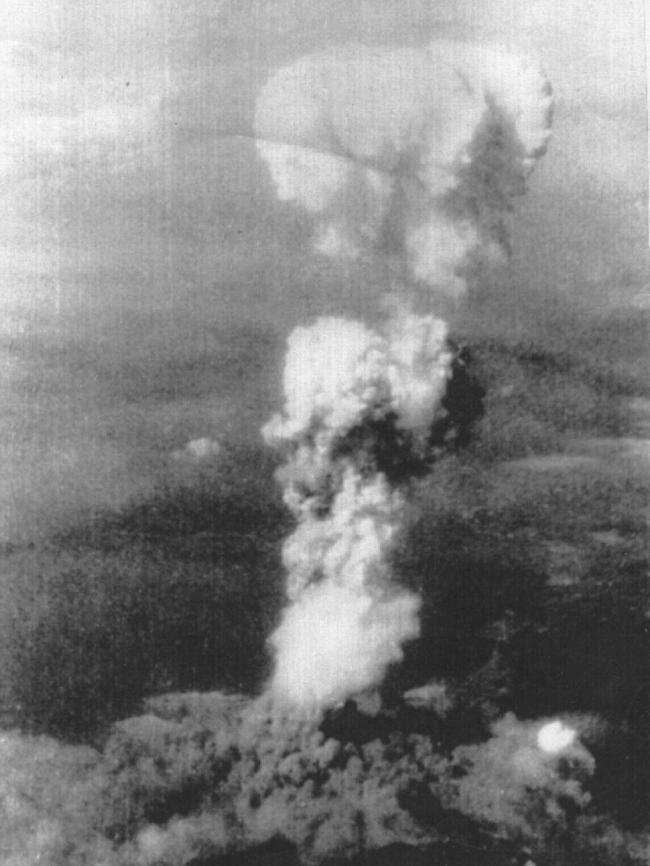

It is 77 years, two months and two weeks since a nuclear device was used as a weapon. On Tuesday, it will be 60 years since the world’s brush with that threat as US president John F. Kennedy went toe to toe with the Soviet Union’s Nikita Khrushchev over the missiles Khrushchev had secretly planted on Cuba, less than 170km from Florida.

Asked the odds of a nuclear war with the USSR, Kennedy responded at the time: “Between one in three and even.”

And we would be mistaken to believe it was an isolated incident. In November 1983, as the NATO countries conducted war games in Belgium called Able Archer – a test of their nuclear response to an escalating conflict with the Warsaw Pact nations – the then recently installed Soviet leader, Yuri Andropov, was told it was a ruse for a real attack on Moscow.

Andropov, a bellicose and uncompromising former KGB chief dying of kidney disease, was served by an equally aggressive defence ministry that weeks before had shot Korean Air Lines flight 007 out of the sky, killing 269 innocents, including American anti-communist crusader US congressman Larry McDonald, and four Australians: Neil Grenfell and his wife Carol Ann, and their children Noelle Anne, 5, and Stacey Marie, 3. (Mrs Grenfell’s father, Paul Moline, was chief sub-editor of The Australian when he and his son drowned off the NSW coast in 1974 after their boat capsized in a storm.)

Days later, a computer error in the USSR’s missile early-warning systems indicated the US had launched an intercontinental ballistic missile, and then four more. Fortunately for the world, the experienced Stanislav Petrov was on duty. The Russian lieutenant colonel reckoned it was faulty software and overruled the retaliatory strike.

As Able Archer ramped up, the Soviet Union put nuclear stations in Eastern Europe on full alert and began loading nuclear warheads on to planes. Sensing a perilous over-reaction, the US called a halt to the exercise.

Since the February invasion of Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin has been threatening not to be restrained by the decades-long nuclear taboo, placing his nuclear forces on high alert with perhaps a plan to end his army’s humiliation – the Ukrainian David has been quickly recovering territory from the retreating Russian Goliath – with a tactical nuclear weapon.

After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we have an idea what that would look like. The question is what would be NATO’s response. Ukraine is not a member of NATO so article five, which is at the heart of its agreement – that “an armed attack against one or more of them … shall be considered an attack against them all” – does not come in to play. But nuclear fallout is hardly governable, and in any case will in large part be driven by the weather. Ukraine’s neighbours, including NATO members Poland, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia, might consider nuclear clouds across their lands as an aggressive act demanding a military response.

France is a founding member of NATO and its President, Emmanuel Macron – clearly no poker player – may have given the West’s game away: “France has a nuclear doctrine that is based on the vital interests of the country and which are clearly defined. These would not be at stake if there was a nuclear ballistic attack in Ukraine or in the region,” he said, the shorthand of which is that unless France itself it attacked Macron’s nuclear weapons stay in their silos.

David Petraeus, the retired four-star general who commanded the US forces in Afghanistan and oversaw the coalition forces in Iraq, and later served as director of the CIA, believes NATO is unlikely to enter a nuclear engagement with Russia.

We spoke after Putin’s latest threat to use “all the powers and means at our disposal” to defend Russia, in which he now includes recently annexed eastern regions of Ukraine. Petraeus believes we are not as close to nuclear conflict as in 1962, but that the “possibility is greater than it was before Putin’s recent sabre-rattling”.

While he believes we must take Putin’s threats seriously, he thinks such a confrontation “very unlikely”. Nonetheless, he raised the comments of US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, who recently said he had alerted a Russian counterpart that the response to such an attack on Ukraine would be “catastrophic”.

“That is a very significant statement, and in my view it means that the US – and likely other countries – would respond with military action, not just additional economic sanctions, diplomatic condemnations, and other measures,” said Petraeus, who stood down from the CIA in 2012 after it was revealed he had had an extramarital affair with his biographer.

“I suspect that this is part of a deliberate effort by American leaders, together with leaders of other nations, to deter Russian use of nuclear weapons by convincing Putin that such use would result in Russia being in a situation even worse than the stark reality that faces Russia in Ukraine at present.”

This was in reference to Ukraine’s “impressive” mobilisation of troops and arms with the robust support from the West. “Ukraine now has a larger, more capable military … than does Russia – and that situation appears irreversible to me, though much hard fighting and tough casualties lie ahead and Russia will retain the capability to ‘punish’ Ukraine with missile, rocket and drone strikes on civilian infrastructure and facilities, such as electrical power generation facilities and major urban centres.”

Sir Jeremy Fleming, director of London’s Government Communications Headquarters, for whom Petraeus has considerable regard, said last week be believed Putin was “a long way off using nuclear weapons”. Petraeus agrees, but will not speak about what he knows of the steps between an order from Putin for an attack and the fact of it.

“That is too sensitive to discuss for someone who held the positions I did,” he said.

The day in 1952 when Petraeus was born, Frankie Laine’s song, The Ballad of High Noon (Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin’), was in the top 10. Coincidentally, it was composed by Ukrainian-born Dimitri Tiomkin. Might today’s conflict be the West’s high noon? “I don’t think so, though it is certainly a very consequential moment … this is Ukraine’s War of Independence, and we need to do all that we can … to enable them to achieve their objective.

“Ironically, Vladimir Putin set out to make Russia great again; however, what he has really done is make NATO great again – galvanising a degree of NATO unity not seen since the end of the Cold War and pushing Finland and Sweden, two historically neutral countries, to join NATO,” Petraeus said, adding that the West had hesitated over Ukraine’s bid for NATO membership and “that reluctance has been disastrous”.

When coffins of Russian soldiers were returned in large numbers during its disastrous invasion of Afghanistan, the boys’ mothers became a noisy and effective protest group making their countrymen aware of those losses. Many multiples of Russian soldiers have been killed in Ukraine.

“The protests over the losses in Afghanistan took years to materialise, and the war in Ukraine is just approaching the eight-month mark,” said Petraeus, who is convinced internal opposition to the war will gain momentum in Russia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout