US Democratic party’s primary concern

The Democratic primary in New Hampshire this week showed the race to choose a contender to take on Donald Trump is wide open.

The Democratic primary in New Hampshire this week showed the race to choose a contender to take on Donald Trump is fluid, amid intense friction between the party’s liberal and moderate wings and between the old and the new.

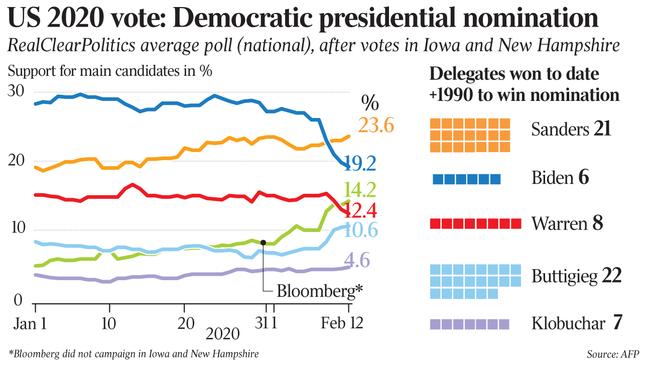

The second state ballot to find the party’s presidential nominee left Bernie Sanders as the narrow frontrunner after a close victory in New Hampshire and his virtual dead-heat with the moderate Pete Buttigieg in Iowa last week.

America may not be ready for a socialist president but, to the horror of the party’s moderates, Democratic voters are flirting seriously with the idea.

The New Hampshire poll was virtually home territory for Sanders, who is a senator for Vermont, which borders New Hampshire.

But instead of running away with the contest, he finished up with two untested new moderates in Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar breathing down his neck and collectively winning 44.2 per cent of the vote.

This suggests that a large chunk of Democratic voters want a moderate candidate to take on Trump in November but can’t agree on who that candidate is. This battle between the moderates risks splintering their vote, which would play into Sanders’s hands.

Here’s how the contenders stand after round two.

Amy Klobuchar

Anyone who thinks this Democratic presidential race is predictable was not standing in the ballroom of the Marriott Hotel in Concord, New Hampshire, when Klobuchar, 59, walked out to celebrate her result in Wednesday’s primary (AEDT).

“Hello, America. I’m Amy Klobuchar and I will beat Donald Trump,” the Minnesota senator told a room full of ecstatic supporters waving “Amy for America” signs. “My heart is full tonight … we have beaten the odds every step of the way.”

Klobuchar had unexpectedly leapfrogged the more high-profile Joe Biden and Elizabeth Warren to grab third place in the New Hampshire primary. Suddenly a serious player in the race, she then gave a short version of her folksy and personal stump speech to a rare national television audience.

She spoke of her struggles with her alcoholic father and how it inspired her to fight to combat addiction, and about how she was thrown out of hospital with her ill newborn daughter — an experience that drove her to fight for better healthcare.

She finished by telling a story she repeats at all her rallies to illustrate her apparent empathy for people in contrast to Trump.

“I think of a story about president Franklin Delano Roosevelt. After he died, his body was transported by train through America,” she said. “At one station, a reporter asked a man who was in tears if he knew President Roosevelt. And the grieving man said, ‘No, I didn’t know President Roosevelt. But he knew me.’

“He knew me. That is what is missing from our politics right now. Empathy. Caring. A sacred trust between the citizens and their president. And that is what I want to restore.”

Klobuchar, a midwesterner with a moderate and centrist policy platform designed to appeal to those Trump voters who abandoned the Democrats in 2016, previously has polled mostly in single digits and was not considered to be a heavyweight challenger for the nomination.

But she has grown on voters. She has a sense of humour rarely seen on the campaign trail and, after a strong performance in last week’s Democratic debate, crowds suddenly were flocking to her town hall talks in the final days of the New Hampshire campaign.

In the Iowa caucus, Klobuchar came fifth with only 12.3 per cent of the vote. Yet in New Hampshire, after a strong performance in last week’s Democratic debate, she surged to win 19.8 per cent, behind Sanders on 25.7 per cent and Buttigieg on 24.4 per cent.

Bernie Sanders

Sanders, 78, declared the New Hampshire result a “great victory” that marked “the beginning of the end for Donald Trump”.

On paper, the left-wing firebrand will be difficult to beat, even if many Americans blanch at the prospect of a self-described democratic socialist in the White House.

His anti-establishment message — honed ever since he honeymooned in the Soviet Union — calls for Medicare for all, including the abolition of private health insurance, a minimum wage of $US15 ($22.20) an hour, free college tuition, wealth taxes and an ambitious climate change agenda.

His agenda has a powerful appeal to millennials and younger voters who stand to reap the many handouts he promises.

Sanders has turned a large and remarkably loyal following into a powerful volunteer organisation across the country.

He describes his followers as a “grassroots movement”, and he predicted in front of more than 4000 people at a rally in New Hampshire on Tuesday (AEDT) that “this turnout tells me why we’re going to win here in New Hampshire, why we are going to win the Democratic nomination and why we are going to defeat the most dangerous president in the modern history of America”.

Yet while Sanders has performed well in Iowa and New Hampshire, his supporters have not stormed the ballot boxes with the enormous turnout he predicted. In 2016 Sanders won New Hampshire over Hillary Clinton, receiving 60 per cent of the state’s Democratic primary vote, and while there are far more candidates this time, he won only a little more than a quarter of all votes cast.

Pete Buttigieg

Buttigieg, 38, the former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, is the shiny new choice of many moderates. He doesn’t have the natural charisma of a young Bill Clinton or Barack Obama and he can come across as too rehearsed, but Buttigieg is a strong campaigner who says everything moderate Democrats want to hear.

“Thanks to you a campaign that some said should not be here at all has shown that we are here to stay,” he said after coming a narrow second in New Hampshire. “We will welcome new allies to our movement at every step.”

Buttigieg sells himself as a candidate for generational change with a centre-left platform that does not include sweeping promises such as Medicare for all or free college tuition for all.

He is from the midwest, a region where Democrats must perform well to beat Trump, and he has momentum after Iowa and New Hampshire.

But the path for Buttigieg from here becomes more difficult. As a virtual unknown, he had to have a breakout result in the first caucus state of Iowa, so he spent more time there than any other candidate. Then, after coming equal first, he received a giant bounce in the polls in New Hampshire to come a close second.

But Iowa and New Hampshire are filled with white, older voters and Buttigieg now faces contests in racially diverse states such as Nevada and South Carolina, where he has spent little time.

Polls show his support among African-Americans — a key group for any Democratic nominee — is only 4 per cent, partly because he is damaged by claims that he neglected black issues while mayor of South Bend. These include sacking a black police chief and pursuing a marijuana possession policy that resulted in a disproportionately large number of black people being arrested.

But perhaps more problematic is that African-American voters, especially deeply religious people, appear to be more concerned about his homosexuality than white voters are. Buttigieg argues that minority voters do not know him well and that his support will grow. With the Nevada and South Carolina primaries being held in the next two weeks we are likely to learn soon whether Buttigieg is a flash in the pan — a white candidate for whites — or a serious national contender for the Democratic nomination.

Klobuchar faces a similar challenge to Buttigieg. She campaigned heavily in Iowa and New Hampshire rather than elsewhere, and her popularity among African-American voters is even lower than that of Buttigieg.

Michael Bloomberg

If Buttigieg and Klobuchar crash and burn in the more diverse states, it will open a path for billionaire Michael Bloomberg, 77, to lead the way for the moderate Democratic voters.

The former New York mayor has skipped the first four primary states and will enter the contest from Super Tuesday on March 3, when 14 states vote and one-third of delegates are awarded.

Bloomberg has poured an astonishing $US350m ($520m) of his own wealth into his campaign advertising, prompting accusations that he is trying to buy his way to the presidency.

But, ultimately, Bloomberg can succeed only if voters find his message plausible, and that won’t be known until we see how he performs next month.

The question facing Bloomberg is whether his late-entry strategy will work as the intensity of his campaign grows. A controversy over his 2015 comments in support of New York’s policing policy of “stop and frisk” demonstrates that while Bloomberg has successfully generated attention for his campaign by skipping the early voting states, flooding the airwaves with ads and travelling to multiple states a day, he hasn’t faced the traditional scrutiny that comes with being a presidential candidate.

Bloomberg hasn’t participated in any of the debates and, as he gains traction, rival campaigns are devouring his past work and comments to seize on anything that could hobble him. On Thursday (AEDT) he defended his 2015 comments about the controversial “stop and frisk” policing tactic that was found to affect minorities disproportionately.

But Democrats in the states that vote on March 3 say they are awed by the breadth of Bloomberg’s operation and warn that it can’t be discounted. “Not only has he spent an enormous amount of money to get on air — more than I’ve ever seen a Democrat spend in Texas, and not just on TV but on Facebook, social media,” says Texas Democratic chairman Gilberto Hinojosa, “but what he’s done is hired a big chunk of the Latino and African-American leadership to work for him and bring communities of colour together behind his campaign.”

Joe Biden

Another big question to emerge from New Hampshire is whether Biden, the establishment moderate and former US vice-president, and establishment progressive Warren can recover their campaigns after their poor showings in Iowa and New Hampshire.

“It ain’t over, it’s just getting started,” a defiant Biden said after he came fifth in New Hampshire with only 8.4 per cent of the vote after his fourth place in Iowa.

“We just heard from the first two of 50 states. Not half the nation. Not a quarter. Not 10 per cent. Two. Where I come from, that’s the opening bell.”

Biden is betting his recovery almost entirely on his “firewall” state of South Carolina, where he is polling strongly because of support from African-Americans, who make up 60 per cent of primary voters in the state.

But momentum is everything in politics and Biden will struggle to keep his sinking campaign afloat unless he can reverse his fortunes fast.

His campaigning has been lacklustre and one-dimensional, promising a return to the key policies of the Obama administration and modelling himself as the anti-Trump.

“I’ve lost a lot in my life,” he now says at the close of his live events. “And I’ll be damned if I’m going to stand by and lose my country too.”

But Biden appears to have misread the country’s mood and the hankering among Democrats for something new.

It is Biden’s third tilt at becoming president and, according to Democratic strategist James Carville, people forget that he has never been a good campaigner.

“He is one of the most admirable people I’ve ever known,” says Carville. “But he’s never been a good candidate.

“This is not his first rodeo, and he ain’t roped a cow yet.”

Elizabeth Warren

Warren, 70, also doesn’t look like she is going to snare a cow after finishing fourth in New Hampshire with only 9.2 per cent of the vote, after placing third in Iowa.

Warren, whose big-spending liberal platform rivals that of Sanders, maintains she is going to stay in the fight, but it seems that Sanders is the chosen one for liberal Democrats.

It’s a surprisingly fast fall for Warren, who was the frontrunner in the field for much of last year. She stumbled in the polls when she promised to delay her Medicare-for-all plan and when she claimed it would not lead to higher taxes for the middle class — suggestions Sanders openly rejected.

Warren or Biden would have to make history to win the nomination from here. No Democratic nominee has ever come lower than second in New Hampshire.

But US politics is full of firsts these days. Trump is the first president without military or political experience. Sanders would be the most socialist occupant of the White House yet. Buttigieg would be the first gay president. And Klobuchar would be the first female president.

The Democratic race is already confounding the pundits, and the contest has only just begun.

Additional reporting: agencies

Cameron Stewart is also US contributor for Sky News Australia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout