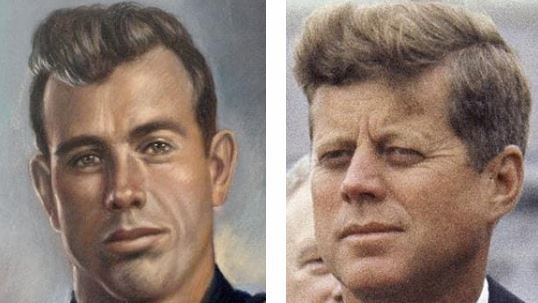

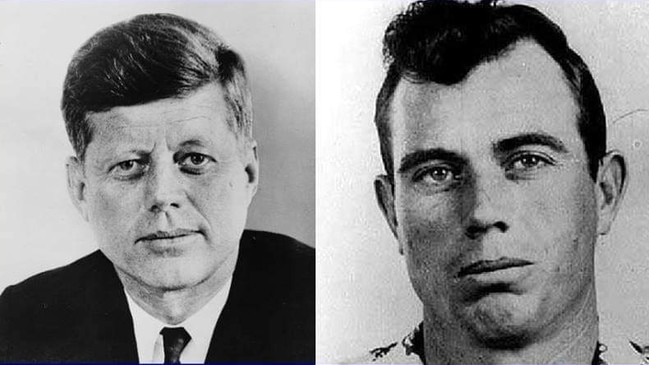

Untold story of the JFK assassination: murder of JD Tippit

We all know John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, but often neglected is the story of the second murder that took place that day in Dallas, Texas.

We are already almost 60 years into all their dead tomorrows. In 1963, two Americans at work, one aged 39, the other seven years older, were shot dead on the streets of that country’s ninth biggest city. One at 12.30pm, the other 46 minutes later. The younger man came from rural East Texas poverty; the other from educated generational privilege. Each served their country in World War II, but oceans apart. What else they had in common was the man who killed them: Lee Harvey Oswald.

At least the facts of the murder of Dallas police officer JD Tippit are uncontested. Moments after the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy on Friday November 22, 1963, as the presidential motorcade swept through the city, Oswald left the Texas School Book Depository on Dealey Plaza, caught a bus and a cab heading towards Oak Cliff off the southwest border of the CBD. Much of the area was blocked off as many thousands lined the route for a glimpse of the president and his glamorous wife Jacqueline. (Conveniently, the president’s route from the airport through downtown had been published by the Dallas Morning News, a newspaper founded by George Dealey after whom the infamous Dallas landmark had been named. His statue overlooked the plaza that day as history unfolded.)

Soon after the shooting, a police dispatcher radioed for patrol cars to head towards Oak Cliff, a then homogenously, some would say defiantly, white, middle class precinct that would produce singer songwriters Michael Murphey (Wildfire), Edie Brickell (now Paul Simon’s wife) and guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan.

Tippit was in the area when the dispatcher announced over the police radio what had happened at Dealey Plaza and for officers to look out for the suspect – a witness had seen Oswald at the window before and moments after he heard gunfire, another as Oswald hurried down the street. Combining their recollections, police described the wanted man as a “white male, approximately 30, slender build, height 5 foot 10 inches, weight 165 pounds”. That’s a man about 1.75m weighing 75kg. Oswald was just 24, somewhat shorter and weighed precisely 68kg – as detailed at his autopsy two days later. But Tippit’s 11 years in uniform had honed his detective senses and he recognised something amiss about the furtive stranger. Six witnesses to what was about to happen agreed that the man they later knew to be Oswald suddenly turned around to walk in the other direction, perhaps he’d seen the marked police vehicle.

Tippit – the JD initials did not stand for anything, his father had read a book about a character called JD of The Mountains and liked the sound of it – knew the president had been shot, but not that he had died. Kennedy was declared dead at 1pm at the city’s Parkland Hospital. Tippit had 16 minutes to live; the fellow he was approaching just two days and seven minutes. It was a one-man patrol, so Tippit was in the driver’s seat. He pulled up alongside the kerb and summoned his suspect to the car through the passenger-side window.

Tippit left the car and walked around the front and engaged Oswald in conversation for up to 20 seconds. Then Oswald produced a .38 revolver and shot him three times in the chest. When Tippit fell to the ground he shot the officer in the right temple, killing him.

Oswald sprinted off dropping spent cartridges from his pistol. Shocked witnesses kept an eye on him, another used Tippit’s crackling police radio to tell the dispatcher what had happened.

Oswald was seen entering the Howard Hughes-owned Texas Theatre where he sat inconspicuously in the third back row and watched the Korean War drama War is Hell. Police were there in minutes to arrest him. “Well, it’s all over now,” a resigned Oswald muttered indistinctly. He had no idea.

That night, a still shocked and grieving Robert Kennedy, the US Attorney-General and the president’s brother, gallantly called the Tippit family home to speak to the officer’s widow, Marie. Robert said that he and his sister-in-law were “extremely sorry and wanted to offer our deepest sympathy in this time of grief”.

At first, Marie, a mother of three children aged 13, 10 and four, held up well. She told the president’s brother “I certainly know how she feels. But, you know, they were both doing their jobs. They got killed doing their jobs. He was being the president and JD was being the policeman he was supposed to be.” The next day, Lyndon B Johnson, not 24 hours into his presidency, also called Marie.

Days later, Jackie Kennedy wrote to Marie, but by the time the letter arrived Marie was traumatised, had been prescribed tranquillisers, and was unable to respond. The note stated the Kennedy family felt partly to blame for Marie’s husband’s death and added: “I hope you’re not bitter toward us because of what happened.”

Marie never was. A friend responded, with her approval, and, in answer to Jacqueline’s offer to contact Marie if there was any help she could give, asked if the former First Lady might send a photograph of the Kennedy family. Not long after a package arrived with a framed photograph of the Kennedys at their holiday home on the Massachusetts coast. Beneath it, Jackie had written “For Mrs. J.D. Tippit, with my deepest sympathy and the knowledge that you and I now share another bond – reminding our children all their lives what brave men their fathers were – With all my wishes for your happiness, Jacqueline Kennedy.”

Jackie explained that the eternal flame she planned for her husband’s grave would also burn forever for Marie’s husband.

Marie, who went on to marry another policeman, died from heart failure after contracting Covid last year aged 92.

Tippit’s life and death were in some ways unremarkable – on average, two Dallas police officers are killed each year. In hindsight, of course, they were anything but.

He had been born to battling sharecropping cotton farmer Edgar Tippit in the little town of Annona near the Oklahoma border. It was challenging physical work in all weather, but Edgar lived to 104, passing away only in 2006. He and his neighbours didn’t have tractors; their ploughing and fieldwork was done with sturdy mules shared by the community. It was and remains a poor place. At last count, about a fifth of its 282 residents remain under the poverty line. The average person there is 39 years old – Tippit’s age.

Like so many, Tippit signed up to defend America following the shocking Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor. Working the cotton fields was vital to the war effort, but Tippit felt he owed it to those already fighting to join them. He was ploughing a field behind a team of mules one morning when a piece of machinery broke. He unleashed his mules, calmly walked into town and signed on for the army, eventually becoming a parachute infantryman in the 17th Airborne Division. He may not have arrived in Europe until the final year of the war, but there was plenty of blood still to be shed, much of it American, as the Allies pushed across the Rhine – and in Tippit’s case flew over it – into German territory.

On the day that John Kennedy retired from the US Navy on March 1, 1945, after various injuries and outlandishly brave antics to save his men from the sunk PT 109 in the Solomon Islands, northwest of Vanuatu, Tippit was being briefed on their daring mission to parachute behind the lines. These men were equals on that score. Kennedy remains the only president to receive a Purple Heart.

When Tippit became aware he had been listed as a candidate for one, he asked that his name be struck off. But he came home with a Bronze Star.

After the war, urged on by his pushy father, Kennedy sought to be considered for a Silver Star. He was twice offered a Bronze star, but turned them down.

Inescapably, the stories of Kennedy and Tippit diverged again after their deaths. Kennedy, Tippit and Oswald were buried on the same day – November 25.

The service for the slain president was a nationally televised event held at Washington’s St Matthew’s Cathedral before 1200 invited guests, many of them world leaders, after 250,000 had filed past his coffin. An hour later he was interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

Tippit’s suburban funeral was attended by 1500 mourners, at least 800 of them colleagues. Police outriders attended the hearse as it travelled to the Laurel Land Memorial Park, about 10km south of Dallas. Tippit was laid to rest in a new area, the Memorial Court of Honour, that had been established the year before to accommodate those killed in the course of duty. He became its first resident. His headstone reads simply “Devoted husband and father” and bears his police badge number – 848. It is not an attractive spot – and a busy road runs past and on to the local 7-Eleven, an Exxon petrol station and Moe’s Burgers. Almost no families have elected to have their fallen buried there and it appears to receive few visitors. Tippit’s eldest son, Allen, who died of lung cancer aged 64, is elsewhere in the grounds. So too is Stevie Ray Vaughan.

Full-time crook and part-time FBI informant, nightclub owner Jack Ruby famously shot Oswald dead at Dallas police headquarters on Sunday, November 24. Ruby had been at the Dallas Morning News booking ads at the time Kennedy was killed. That day’s newspaper carried a full-page, black-bordered advertisement approved by its publisher Ted Dealey (George’s son). It was headlined “Wanted for treason” and carried a photograph of Kennedy who is described as being soft on communists. Kennedy had met and disliked the surly, uncultured Dealey. When he saw the newspaper the morning of his assassination, he said to Jacqueline: “We’re heading into nut country.”

Ironically, the nut turned out to be a communist. Like Kennedy, Oswald was pronounced dead at the Parkland Hospital, and was buried, almost in secret, the following day at Rose Hill Cemetery, 45km west of Dallas. Oswald’s wife, Marina, and mother, Marguerite, were there.

A few police officers attended along with, handily, some reporters who reluctantly acted as pallbearers. A defiant Marguerite addressed them: “Lee Harvey Oswald, my son, even after his death, has done more for his country than any other living human being.”

Proving that there is no rest for the wicked, his headstone, which simply read Oswald, became a tourist drawcard and was stolen. Marguerite had another installed (and when the original was recovered she kept it at home). She died in 1981 and was buried alongside her son. But later that year his remains were controversially exhumed to test – and disprove – a theory that it was a Russian spy acting as Oswald who had shot the president.

Oswald was reburied in a new casket to replace the waterlogged original. In 2010, the old casket was auctioned by the funeral home, with an anonymous buyer picking it up for $130,000. Oswald’s brother Robert, who had opposed the exhumation, went to court claiming he owned the coffin. A Texas judge agreed and Robert was awarded that same amount.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout