Ukraine invasion: Military history is dotted with stories of Davids felling Goliaths

The Ukrainian defence forces are up against one of the world’s biggest armies — but we should not take for granted that they cannot prevail.

Russia’s army dwarfs that of Ukraine, its most recent chosen enemy.

Along with more than a million soldiers, its armada of tanks is the world’s largest, and it has more ballistic and cruise missiles than anyone. It has a vast array of military hardware, secret germ warfare stocks and 2000 tactical nuclear weapons.

That no one has used a nuclear weapon since 1945 would suggest some global taboo. Vladimir Putin doesn’t understand taboos.

He enjoys ostentatious displays of brute strength. He lacks compassion. He is delusional and possessed of a grandiose self-esteem, all of which experts rate as the traits of a psychopath. Think Mao, Hitler, Stalin and Amin – all of whom were happy to commit acts of grotesque evil to achieve their goals. Last week children were being murdered in Ukraine on Putin’s behalf, some shot by Russians soldiers in a manner we cannot publish. Then they targeted a maternity hospital – that was to prevent Ukrainians even being born. The world may wonder about how long Putin can dodge his conscience, but a psychopath doesn’t have one.

Putin’s latest war started in 2014 with a shark bite into Ukrainian territory when he seized Crimea. When his victorious soldiers came home they were given medals minted with the words “For the return of Crimea”.

This year, he grabbed two more “Russian” lands, recognising “the independence and sovereignty of the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Luhansk People’s Republic” – breakaway states on Russia’s border.

Following that, in a strange speech on television addressed to Ukraine’s soldiers – amid a stream of hectoring incontinence – Putin described their government, led by Volodymyr Zelensky, a Russian-speaking Jew, of being “a gang of drug addicts and neo-Nazis”.

He parked 190,000 troops on Ukraine’s border along with a 64km convoy of tanks. A taste of what was to come. Ukraine has only 245,000 soldiers. Waving a few false flags, Putin sent in his men with three days’ provisions expecting a walkover in which Ukraine’s women would place flowers in the Russian soldiers’ rifles as the men, with heads bowed, handed over theirs.

Putin thought he’d call a war and that no one would come. Not Ukraine. Not its neighbours. Not NATO. Nobody. But the Ukrainians have come and David’s stones are chipping away at Goliath’s generals and soldiers.

In a stunning series of reversals, while bringing down Putin’s helicopters and jets with the equivalent of slingshots, and killing perhaps 11,000 Russian troops, the Ukrainians’ resistance has proved stout. It seems these “drug addicts and neo-Nazis” are fearless, inventive and nimble. Putin is sending much more their way and must certainly prevail. But maybe not. Little armies have beaten bigger ones in battles before today. Military history is dotted with their against-all-odds victories.

In the annals of military improbability, perhaps no contest comes close to Israel’s victory in 1967’s Six-Day War.

Jews were allowed to return to their ancestral home – after several millennia and a Holocaust – by United Nations Resolution 181, in November 1947. It won a healthy majority but, tellingly, among those voting against it were Israel’s soon-to-be-neighbours, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria and Turkey. Just a few hours after Israel declared independence it was defending itself against attack by Arab militias and the forces of those No voters, and a few others. It suffered dreadful losses, but survived.

Those nations then looked on with envy as Israelis – with next to no resources and little water – built towns and then cities, turning granite into green within a flourishing liberal democracy, while constantly under terrorist attack. On May 24, 1967, Egypt’s president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, said that if there were to be a war “our basic objective will be to destroy Israel”. Planning for that war was well under way. Ten days earlier Nasser had removed the United Nations Emergency Forces stationed on the Sinai Peninsula. Two days later he blockaded the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping and began massing 100,000 troops on its border. Everyone knew what was coming.

Israel’s combined enemies, with more than 500,000 troops, almost 1000 combat aircraft and 2500 tanks between them, were about to take on Israel, which had 50,000 troops (and 200,000 civilian reserves, not that civilian society could persevere if these men and women were activated for more than a few weeks), about 300 aircraft and 800 tanks.

What happened next was perhaps the most stunning military contact of the 20th century.

With the attack to obliterate the world’s newest country imminent, Israel began practices to launch, land and refuel its aircraft so they might be able to carry out three, perhaps, four turnarounds dropping bombs on strategic targets on each mission. By Sunday, June 4, 1967 they thought they were prepared and at 7.45am the following day they readied their operational jets – almost 200 of them – and launched themselves at the future. The Israeli aircraft flew out low over the Mediterranean in a north-westerly direction and then turned sharply left before heading towards Egypt. They bombed and strafed the enemy’s planes and tarmacs. Even unaffected aircraft – more than 300 were destroyed – were unable to take off. Israel lost 19 planes.

Meanwhile, Israel’s compact land forces crept up on the mighty Egyptian infantry and tank columns, unexpectedly from northern Sinai, and in fierce fighting outmanoeuvred the enemy over the course of two days. The Egyptians’ Russian-built WWII-era tanks proved inferior to the Israelis’ newer French, British and American armour. Meanwhile, Israel’s air force was turning around its fighters in less than eight minutes and giving cover to its tanks and footsoldiers. Relatively low-level attacks from Jordan were repelled with few losses and Israel captured the West Bank. Syria held off its attacks after being advised by Cairo that Egypt had conquered Israel. When it realised this was fake news, it started shelling from the Golan Heights, taking a heavy toll.

Eventually many Egyptian warriors abandoned their equipment and retreated. So many surrendered the Israelis kept only senior officers, sending the others away. In Jerusalem they decided not to send in heavy equipment for fear of damaging its Old City, but in bitter and costly – to both sides – street-to-street and man-to-man fighting Israel prevailed.

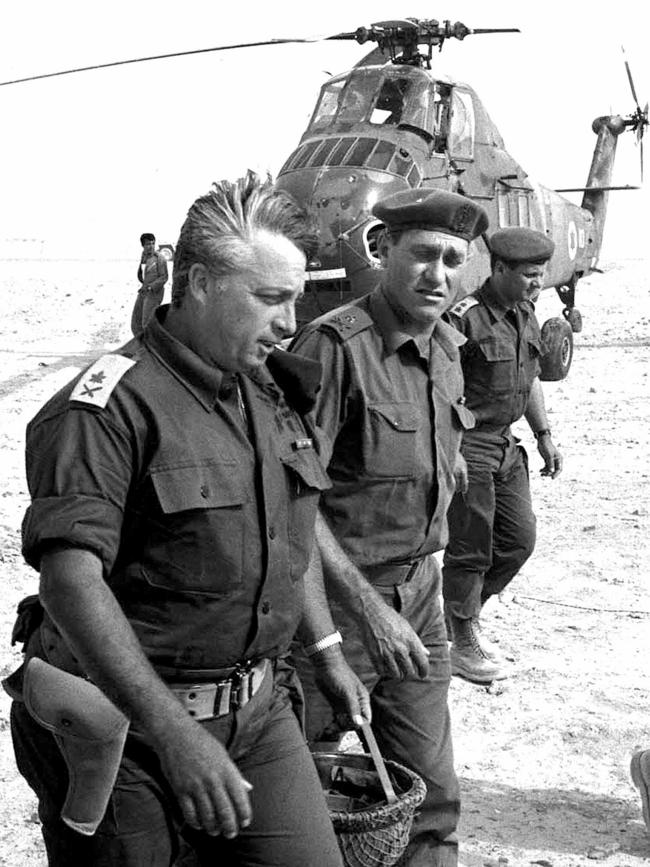

By the time the UN Security Council ordered a ceasefire, just less than 1000 Israeli defence force personnel lay dead along with 20,000 Arabs. Israel’s Chief of the General Staff, Yitzhak Rabin, later to become the nation’s first native-born prime minister, summed up his country’s unlikely victory: “Our soldiers (understood) that only their personal stand against the greatest dangers would achieve victory for their country and for their families, and that if victory was not theirs the alternative was annihilation.”

That same thought must be driving the Ukrainian soldiers’ selfless bravery today.

Another remarkable battlefield victory took place in December 1971 during the 13-day India-Pakistan War. The conflict followed the push by nationalists in what was West Pakistan for their own country. Bangladesh was born. But Pakistan believed India had encouraged and assisted the breakaway movement and on December 3 that year launched a peremptory attack on various Indian air bases and radar facilities.

The following day up to 3000 Pakistani troops accompanied by 45 tanks stormed an Indian border post, Longewala, on India’s northwest border. About 120 Indian soldiers were stationed at the sleepy outpost. At 10am, Captain Dharamveer Singh was on patrol when he heard a thundering in the distance. He called his headquarters, but they had doubts Pakistan would attack India with a tank battalion. He held the phone out so they could hear them. They remained unconvinced, or didn’t hear clearly through the crackly connection. Late that night the Pakistan tanks came into view. Singh’s commander, Major Kuldip Singh Chandpuri, had to decide either to retreat, or fight and wait for back-up six hours off. He stayed, with his sole advantage being an elevated position in the sand dunes. His only “vehicles” were 10 camels, part of the Border Security Force, five of whom were shot dead as the enemy approached.

They had time to lay just a few landmines, but stretched their three-string barbed wire widely around the base, indicating a much wider minefield. The Pakistani tanks stopped at this theatrical line and some became bogged. Chandpuri’s men, a few metres above them, but from a short distance, fired at the thin tank canopies and disabled some of them, inadvertently setting fire to auxiliary fuel tanks that illuminated the battlefield, enabling the Indians to see the enemy more clearly. They kept them at bay until dawn, at which point the Indians scrambled their locally built jet fighters, which made short work of the easily seen tanks in the otherwise featureless terrain. It was reported that the Indians lost two men, and Pakistan 200, along with 36 tanks. Others were abandoned. A 1997 film, Border, celebrates the victory in typical Bollywood style. Close to the site, a memorial features a rifle in a plinth with a helmet on it and the inscription: “Here we drew a line in blood across the desert, a line the enemy dare not cross.”

The Marne River rises in the northeastern France near the town of Langres, famous for its fortifications built to ward off its enemies at the end of the Middle Ages. The Marne winds across the country and heads to join the Seine in Paris. In 1914, another enemy sat on its shores: Germany. Early on in WWI, Germany’s armies had made short work of its ancient enemy, 75,000 of whom had been killed in recent weeks, 27,000 on one day, August 22.

By early September the enemy had surrounded Paris. French forces were outmanned, outgunned and out of sorts – the so-called Great Retreat from the country’s north had seen the humiliation of the Franco-British forces. The capital was all but encircled by confident and celebrating Germans who believed there were just hours left to see out what the world would come to know as The Great War as they crushed the French capital. They were 45km from Paris, but the “circle” was missing a link.

Spotting this weakness, France’s General Joseph Joffre counterattacked and asked for reinforcements. In the capital, General Joseph Gallieni weighed up his options. He distrusted France’s railway system and so commandeered 600 Renault taxis, which, doing an average two trips each on the night of September 7, delivered 3000 troops, and their equipment, to Joffre, tipping the balance of the war – for the time being. The drivers kept their headlights off and followed each others’ tail lights travelling about 40km/h. Some drivers were grumpy about the order and others were said to have kept their meters running so they could bill the government later. But then much myth surrounds this remarkable event.

Australians too have defied the odds in battle. On August 18, 1966, at the height of the Vietnam War, Australian troops from D Company engaged in the biggest battle for our country since the Korean War. It took place in a rubber tree plantation during a rainstorm at Long Tan not far from the Australian base of Nui Dat. A Vietcong force of up 2500 – who knew this area like the backs of their hands – pinned down 108 Australians who were short of ammunition. The encounter started at 3.40pm and the Australians, with nothing but rubber trees – dripping their milky latex as enemy fire sliced through them – for protection, stood their ground, many of them conscripts.

By 7pm reinforcements had arrived, but 17 Australians were dead and an injured soldier would die later. It was the greatest loss of Australian lives in a single day during that war. In 1987, prime minister Bob Hawke declared that date would be known as Vietnam Veterans’ Day.

You need not be as big as your enemy to win a contest, as some farmers with guns proved to the British Empire during the Boer Wars in South Africa. But you need to be smarter. Military might can defeat military might. Cunning can defeat them all.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout