Ukraine and China concerns expose Australia’s laziness on defence

Australia’s security outlook got much bleaker this week. If only Canberra’s ADF policy had even just 1 per cent of the clarity and purpose that it has on our policy on Ukraine.

“It does change the calculus if Chinese Navy vessels are operating from the Solomon Islands. They are in much closer proximity to the Australian mainland, obviously, and that would change the way we would undertake operations.”

– Lieutenant General Greg Bilton, Chief of Joint Operations

Australia’s security outlook got much bleaker this week. First, it became clear that Vladimir Putin’s invasion will result in at least a great chunk of Ukraine’s territory falling permanently under Russia’s control, even as Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky delivered a stirring and magnificent speech to the Australian parliament.

Zelensky bluntly claimed that Moscow had re-created the worst horrors of the 20th century, promising to enslave and obliterate a neighbouring nation.

Australians are moved by Ukraine’s heroism and have responded with solidarity and strategic common sense. But it’s an easy crisis for us to participate in. It’s a long way away, and our choices are obvious.

Scott Morrison called Putin “the war criminal of Moscow”.

If only Canberra’s policy on its own Australian Defence Force had even just 1 per cent of the clarity and purpose that it has on our policy on Ukraine.

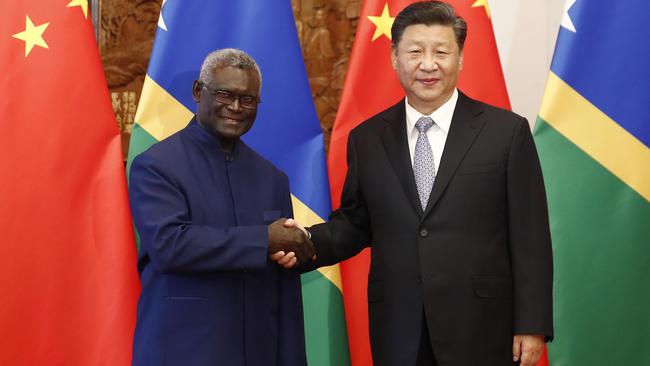

The second piece of bad news was that Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare angrily told his parliament he would sign a security agreement with China, against passionate objections from Australia, New Zealand, the US, and numerous South Pacific nations.

The leaked draft of the agreement said: “China may, according to its own needs and with the consent of the Solomon Islands, make ship visits to carry out logistical replenishment in, and have stopover and transition in the Solomon Islands, and the relevant forces of China can be used to protect the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects in the Solomon Islands.”

Australian intelligence agencies have known for years that Beijing wants a South Pacific military base to intimidate Australia and constrain the US military. Our 2020 Defence Strategic Update declared: “Australia is concerned by the potential for actions, such as the establishment of military bases, which could undermine stability in the Indo-Pacific and our immediate region.”

Sogavare claims this agreement will not lead to a military base. But Beijing wants a base and this agreement takes it a long way towards that end. A Chinese base in the South Pacific would be, as New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern put it, “gravely concerning”.

There is a deep memory of this strategic equation. In World War II, Japan wanted to cut Australia off from the US by bases in the Solomon Islands.

Franklin Roosevelt thought the US would not prevail in the Pacific if cut off from Australia. John Curtin thought Australia might not prevail at all.

So you might think that the prospect of a Chinese base within 2000km of Australia would mean, surely, that we’re racing to develop relevant military capabilities?

Not a chance. The most depressing strategic setback for Australia came in the defence budget, part of the overall federal budget delivered by Josh Frydenberg on Tuesday.

We got a complacent, lazy, negligent, mainly hollow defence budget which delivered just one new relevant capability, funding over 10 years of $10bn for new cyber capabilities in the Australian Signals Directorate.

That’s very good. Three cheers. But apart from that, the defence budget was shockingly nude. In terms of military capability, the Morrison government has been a failure. It delivered, ASD aside, exactly the defence budget you’d expect if there had been no security crisis over the past six years, indeed the past 15 years. There was not one single new capability in this budget. The existing, gravely inadequate capabilities are mostly wearing out. And in several key areas, they are not being replaced.

The defence budget papers are an exercise in labyrinthine opacity.

One uncharacteristically revealing table shows the 30 major defence projects. Guess what comes in at No.4?

The French submarines.

Yep, our fourth-biggest “acquisition” project is paying for a submarine we have cancelled.

That’s very Australian. We have paid about $3.3bn for the French subs. By next financial year’s end, this will be nearly $4bn. Many countries get their whole submarine capability for that kind of money.

But our defence budget apparently has money to burn. For the past two years, Defence has underspent its allocation by about $1bn each year. There is so little happening in defence, our few significant programs are so stalled, that it can’t spend its money. Even the $10bn over a decade for cyber involves very little new money. Most of it will come from other existing programs, which apparently can afford to give it away. There is so little urgency, so little energy, in Defence, when we should be racing to produce capability.

The government wants a medal pinned on its chest because it is implementing the spending amounts outlined in the 2016 White Paper. It’s not producing the capability then envisaged. But it is spending approximately the amount of money it forecast.

It is worth noting that the budget reveals we did not even reach 2 per cent of GNP on defence, as the government constantly claims. This is the NATO minimum. We came in a bit under 2 per cent. This is an unmistakeable sign we are not serious about defending ourselves. Our two closest allies, the US and Britain, both far more secure than we are, both spend a far higher percentage of their GNP on defence.

In 2015, the Australian Defence Organisation produced budget forecasts based on the antique force structure it has had for decades and never allows any government to change. The Air Force had got some new planes, and the Navy had got some new ships. So it was the Army’s turn for new kit.

This didn’t have to be relevant to defending Australia, coping with the maritime challenge that China’s vast defence expansion brings. Instead, Army capabilities had to follow the tradition of allowing us to make tiny, but beautifully formed, hi-tech niche supplemental deployments as boutique add-ons to US expeditionary wars of choice, such as Afghanistan or Iraq.

Obviously a plan designed in 2015, and published in 2016, did not take account of the massive changes to the strategic environment since then.

Scott Morrison and Peter Dutton relentlessly and truthfully alert us to the worst strategic environment since World War II.

But we are doing absolutely nothing about it.

The 2016 program is inadequate today. But in any event, while we are spending the money, we are not producing even the capabilities envisaged then. We’ve cancelled the submarine program and now have no submarine program, merely an aspiration, an intention, for nuclear-powered subs produced with US and British help.

The budget cast in stone the nonsensical idea that these nuclear-powered subs will be built in Adelaide. Is there anyone on the Australian continent who really believes this? The last Collins sub was commissioned in 2003. Even if the Americans agree, and we clear all the vast regulatory hurdles, train from scratch a generation of nuclear engineers, and the Americans are happy to send us vital components of their own already overstretched submarine manufacturing work force, we won’t be doing any building before 2030.

That means it will be nearly 30 years since we build any kind of sub, then we go straight to building nuclear subs.

Will you bet our security on that? Have we ever had troubles or delay building complex navy vessels in Adelaide before?

We won’t get our fleet of eight nuclear subs before the late 2050s, at best. And only our reconditioned Collins – by then surely the most ancient boats at sea – are “it” in the meantime.

The other big capability from the 2016 White Paper is the nine Hunter-class frigates to replace the eight ANZACs. These are already at least two years delayed. They have blown out in size and now have virtually no room for capability expansion once delivered. As currently configured, they are radically under-gunned. And we won’t get the first of them until nearly the mid-2030s.

So, far from responding urgently to the new strategic dangers, we are not responding at all. The Defence Organisation has overruled and outwitted the Abbott, Turnbull and Morrison governments. It proceeds in its stately, almost Gilbert-and-Sullivan fashion, to produce the Duke of Plaza-Toro defence force it was always going to produce.

Consider what it really means if the Chinese establish a naval base in the Solomons. They may not succeed, because every sinew of Australia diplomacy will be working to stop them, as will the Americans, Kiwis and other South Pacific friends. But any prudent Australian government would have to consider there is a real chance the Chinese will get a South Pacific base eventually. They are very determined, they have a lot of money, they are all over the South Pacific, they are very skilled at this sort of stuff, and they are very opportunistic.

What could we do, militarily, that would be relevant to such a development? In 1996, Beijing decided it would work to strip the US of its ability to enforce its will near the Chinese mainland, in what Beijing calls “the first island chain”. The US was vastly more powerful than China, economically and militarily. So Beijing didn’t try to match this power head-on. Instead, it pursued asymmetric capabilities that would impose a disproportionate cost on the US. It began with land-based missiles. It acquired dozens, then hundreds, then thousands of missiles. In due course it added missiles on planes and missiles on ships. This produced what the boffins call an A2AD effect: anti-access/area denial.

The Chinese couldn’t prevent the Americans from hurting them militarily, even in China’s own space, but they could make the cost to the US of operating ships or planes in China’s area extremely high, and impose a huge risk on the US.

Australia is well placed to embark on its own strategy of maritime denial of its sea approaches, out perhaps to 2000km. We do this a bit already with our missile-carrying fast jets – F35s, Super Hornets and Growlers. But we only ever plan to have 100 of these, and at the moment we only have a little over 80. That is way too small a force. We could also put anti-ship missiles on our big Offshore Patrol Vessels.

But the main thing would be ground-based missiles. The US is getting back to making ground-based Tomahawks with a range of about 2400km. Imagine if we had hundreds of such ground-based missiles in diverse locations around the northern Australian coast. Any potential adversary would find their planning massively complicated.

The Australian Army is planning to acquire long-range missiles, but we have no idea when. There is no urgency, you understand. But given the paltry amount of money allocated for it, even in planning documents, you can deduce that the army plans to get them as small-quantity artillery supplements to be used within existing brigade structures, designed for land wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In other words, the army does not plan to use missiles to contribute to the maritime defence of Australia and our immediate region, but for its mis-designed formations created to support the Americans in Iraq and Afghanistan. We are planning to spend $30bn on tanks and heavy armour. We have not had heavy armoured vehicles beyond tanks for many years. There is no prospect these could be used in a final defence of Australia. Any enemy which can travel all the way to Australia and comprehensively defeat our air force and navy will be able to knock out our 90, overweight and immobile tanks, in the unlikely event that we could ever get them into the proximity of the enemy.

If we spent only $10bn on armour, we could use the $20bn savings to double our F35 fleet, or buy several thousand missiles.

That’s the sort of thing a government actually concerned with the military dimension of our national security would do. But it would mean a political war with the army. And government ministers are scared of that.

It’s much, much easier to rely entirely on the Americans and devote all our energy to meaningless, symbolic announcements, and tiny niche capacities that will still earn some favour with the Americans as we deploy them as tiny addendums to US forces.

Even with the wake-up call of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and everything that Beijing’s behaviour over the past five years – including the security agreement with the Solomons – has taught us, we still don’t take our own security seriously.

Volodymyr Zelensky we ain’t.

“We should not take peace in the Indo-Pacific for granted.”

– Defence Minister Peter Dutton