A few liberals take pains to distinguish themselves from conservatives. Likewise, some conservatives take pains to distinguish themselves from liberals (or libertarians). But there is a large overlap between people who respect the Western tradition (especially the English-speaking version) and those who cherish freedom as the indispensable feature of a good life. The poet Tennyson, indeed, had a lovely stanza evoking what has been liberalism and conservatism’s mostly happy marriage:

A land of settled government,

A land of just and old renown,

Where freedom slowly broadens down,

From precedent to precedent

Mill meets Burke

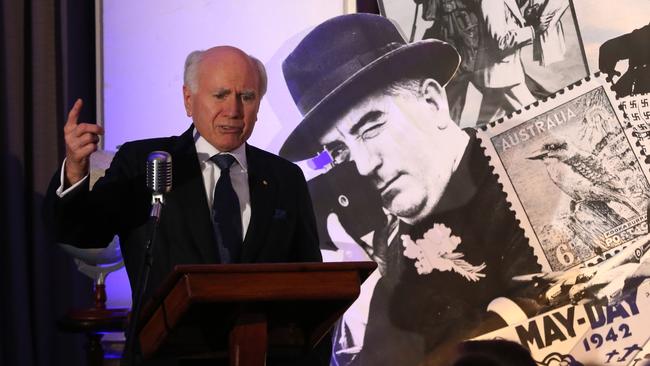

Certainly, the last thing the Liberal Party needs is further polarisation between the instinctive conservatives and the philosophical liberals in its ranks. Howard’s description of the Liberal Party as the political custodian, in this country, of both the liberal tradition of John Stuart Mill and the conservative tradition of Edmund Burke still holds true.

While the Liberal Party sometimes gives less satisfaction to conservatives than it did in Howard’s day, it is still the only political movement capable of giving our country the sensible centre-right government that we need more than ever. The challenge for everyone who wants the Liberal Party to succeed is not to elevate a particular ideological faction into some “winners’ circle” but to find ways of keeping small-L liberals and small-C conservatives together under the same big-L Liberal tent.

Disagreements and debates within political parties are usually less frequent than those between them; but they can be toxic if not well managed. It was Burke, after all, who defined a political party as a body of men working towards the common interest in accordance with a particular principle on which they all agree. Appealing to a modern democratic electorate, though, usually necessitates compromises within parties as much as it does conflict between them. Any political party capable of winning elections is inevitably a coalition of people who won’t always agree on everything but who have found ways to manage their differences and to unite around particular measures that they can all support. Hence Howard’s celebrated metaphor of the Liberal Party as a “broad church”.

The differences between conservatives and liberals within the Liberal Party are not dissimilar to those between the pragmatic right and the ideological left inside the Labor Party. Unacknowledged and unmanaged they can become fierce, even crippling. The challenge of leadership is to keep the political focus on issues where the different strands of internal thinking can more or less be reconciled, and to put those at the heart of a coherent political program; so that it’s the differences with other political parties that become the principal contest that voters have to decide. On those issues where it’s necessary to take a position that might be deeply at odds with some inside your own party, the challenge of leadership is to find something bigger where everyone can agree. If this can’t be managed, a split — small or large — is almost unavoidable and all splits are damaging, even if they don’t threaten the overall unity of the party.

Typical differences

So, what can be taken to characterise a philosophical liberal in Australia today? A liberal typically supports greater freedom, lower taxes and smaller government. A liberal typically thinks that empowered citizens are much more likely than bigger government to produce a stronger economy and a better society; hence, the principal task of government is to shrink. A typical conservative would share his or her liberal friends’ antipathy to bigger, more intrusive government but would often regard other issues as at least equally pressing: maintaining strong alliances and effective armed forces, for instance; promoting the family and encouraging small business; and respecting values and institutions that have stood the test of time. Then there are “progressives”, sometimes describing themselves as “liberals” but, these days, usually more interested in permissive social policies than in liberal economic ones.

Howard sometimes characterised the Liberal Party as “economically liberal and socially conservative”, and that was certainly its centre of gravity in his time. The Howard government was liberal when it reformed the tax system, simplified industrial laws and reduced government spending. It was conservative when it strengthened the US alliance, increased military spending, introduced work for the dole, increased Family Tax Benefits, freed small business from unfair dismissal laws and imposed rigorous national testing on schools. In my time, the Liberal Party was liberal when it cut trade barriers, abolished the carbon tax and the mining tax and cut tax for small business. It was conservative when it stopped the illegal immigrant boats and strengthened national security.

In Howard’s time

In Howard’s time, the most divisive issue was whether Australia should become a republic. The crown had long been an article of party faith. Sir Robert Menzies had famously said of the young Queen Elizabeth: “I did but see her passing by and yet I love her till I die.” When I first joined the party in the 1980s, “we believe … in the constitutional monarchy” was the first item in the “We Believe” statement that all members were expected to subscribe to and that was sometimes recited at the beginning of branch meetings. But when Paul Keating made becoming a republic Labor’s policy after the 1993 election, quite a few Liberals decided that it might be time to change after all.

Howard was a convinced opponent of anything that might shake the checks and balances in a system of government that he termed a “crowned republic”. Yet to manage internal divisions, he dropped support for the monarchy as a formal commitment (even though, to this day, it’s still part of the Tasmanian division’s version of “We Believe”). Liberal cabinet ministers were free to support either side of the argument at the 1998 constitutional convention; and to support or to oppose the 1999 referendum on becoming a republic; which, despite the polls and near-universal media support, was soundly defeated.

Under Abbott

In my time, the most divisive issue was same-sex marriage. More so than with a republic (where there were “liberal” monarchists such as George Brandis), the internal division was largely along instinctual liberal and conservative lines. A “conservative case for same-sex marriage” was indeed made — that it could bring more fidelity and stability to same-sex couples — but very few self-described conservatives went public in support of changing the time-honoured definition of marriage that had been reaffirmed by the Australian parliament as recently as 2004.

Small-L liberals, on the other hand, largely favoured getting the law out of a legislated definition of marriage that activists had turned into the embodiment of discrimination.

Trying to maintain as binding party policy the Howard-era position that marriage had to be between a man and a woman would have meant an embarrassing defeat in parliament as up to a dozen Liberal MPs crossed the floor to support a private member’s bill. As with the monarchy two decades earlier, opposing views were too strongly held by too many MPs for the issue to be resolved by a leader’s call or by a partyroom vote. Hence the plebiscite: it gave party conservatives and party liberals the chance to make their pitch to the community; and either way it would resolve the issue because no democratic politician can fail to heed an unambiguous national vote.

My colleague Dean Smith, as a “constitutional conservative” although a supporter of same-sex marriage, criticised deciding it by a vote of the people in a plebiscite rather of just the parliament in a free vote; but a better conservative position, at least in my view, was that it was best for the whole people to determine something as deeply personal as marriage. After all, the traditional concept of marriage long predated its codification under the Howard government. There was precedent too. The question of conscription — while clearly within the constitutional competence of the commonwealth parliament — had been put to the people, not once but twice, during the Great War.

Conservative unsaid

Until quite recently, except as a term of abuse, “conservative” was not a description that had been widely used in Australia. The first recorded use that I could find was in the commonwealth parliamentary Hansard of 1901 where then-prime minister Edmund Barton denied that he was of “conservative mind”.

For someone who spent much time in England, regarded himself as a friend of Winston Churchill, and over a 50-year public life frequently discussed political values, it’s remarkable that Menzies had so little to say about conservatism and almost never used the term. Menzies’ oft-cited reflection, “We took the name ‘Liberal’ because we were determined to be a progressive party, willing to make experiments, in no sense reactionary but believing in the individual, his rights, and his enterprise and rejecting the socialist panacea”, is sometimes used to make conservatives look like interlopers in the party he formed. Much less familiar is Menzies’ despairing 1974 observation in a letter to his daughter Heather about the party’s Victorian state executive, “dominated by what they now call ‘Liberals with a small l’ — that is to say Liberals who believe in nothing but who still believe in anything if they think it worth a few votes. The whole thing is tragic.”

In a 1965 address to the Liberal Party federal council, Menzies said that the key to its success was that it had been “not the party of the past, not the conservative party dying hard on the last barricade, but the party of innovations”. And it’s true: the Liberal Party has never been “the conservative party”, let alone one “dying hard on the last barricade”, which no rational party, however conservative, would ever choose. No one has ever claimed that the Liberal Party was merely conservative; and it was Burke himself who pointed out that an entity without the means of change lacked the means of its own conservation.

In a 1974 newspaper article, Menzies declared: “When we commenced the Liberal Party we had principles. Principles are apparently nowadays things that are not to be insisted upon because to insist upon them is to demonstrate that you are ‘reactionary’ or ‘conservative’. This, of course, is the most pernicious nonsense. Principles do not change. In the whole of my political life I have never arrived at something that I thought to be a matter of principle lightly or casually. They have represented deep beliefs on my part; and I am old-fashioned enough to believe that principles, once adopted after much thought and consideration, do not change.” This sounds like a still-street-smart elder statesman trying to avoid pejorative labels, not to dissociate himself from political conservatism.

Not a passing trend

The first major Liberal to self-apply the term conservative was Malcolm Fraser. In a fine 1980 presentation to the South Australian state council of the Liberal Party, Fraser said a government concerned to preserve liberal principles and values “must be in some sense conservative”. Conservatism, Fraser said, was not a “passing fashion or trend but a considered and serious realisation that central institutions and values are under threat”. It was an “accumulated disillusionment” with left-wing doctrines that claimed “intellectual and moral superiority” but that when “put to the test either do not work at all or produce unintended consequences which outweigh their supposed benefits”. These included “planning which creates confusion and waste”, he said; “ill-conceived welfare schemes which create monstrous bureaucracies, high taxes and high inflation”; “nationalised industries that fail to deliver the goods”; “attempts to help minorities which succeed only in creating a new dependency”; and “a concern for the environment which degenerates into ritual and dogma”.

It was really only in opposition, during the Hawke-Keating era, that senior Liberals more generally started to examine the conservative elements in their political creed and how these might be in harmony or at odds with philosophical liberalism. Howard led the way, sometimes describing himself as a “Burkean conservative” or once — with equal validity as Burke was formally a Whig — as a “Burkean liberal”.

For my part, I have never felt the need for a qualifying adjective. I regard myself as a conservative but, as such, feel fully at home in a Liberal Party that certainly stands for freedom but which has invariably stood for respect, order and tradition too. In my 2009 book, Battlelines, I said that: “To win elections, parties need policies that strike chords with voters, not with theorists. Hence, it’s the actual appeal that parties make to voters, not the after-the-event tags applied by academics, that should be taken as best characterising a party’s approach … Perhaps it’s enough to say that in some circumstances freedom and in other circumstances a set of rules is the most effective way to encourage people to be their best selves …”

My book prompted a response, some months later, from Brandis in his October 2009 Deakin lecture. In it, he was critical that, “over the past 20 years or so, there had been an attempt to dilute the Liberal Party’s commitment to liberalism. This was particularly so during the two periods of John Howard’s leadership … (and) recently, Howard’s own political legatee … Tony Abbott has taken up the cause of making the Liberal Party more conservative still.”

Yet eight years on, Brandis boasted that it was under the “leader of the conservative side of politics” that same-sex marriage was on the point of being achieved. Perhaps by then he had come to better appreciate the Liberal Party’s conservative dimension; or perhaps he’d worked out that political parties rarely prosper by telling a large section of the electorate that “we’re not for you”.

No to identity politics

Of the two big parties, there’s no doubt which one most appeals to people who think that freedom is what matters most. But what about people who worry about the social fabric or who are concerned that there’s no level playing field on which they can compete? These are far more likely to support a party that’s conservative as well as merely liberal. Certainly, the Liberal Party has enjoyed its biggest wins, under Menzies in 1949, Fraser in 1975, Howard in 1996, and me in 2013, when it has been led from the centre-right.

Still the last thing the Liberal Party needs is our own version of identity politics that tags people as “liberals” or “conservatives” and never the twain should meet.

Regardless of the emphasis that’s placed on the two key strands of Liberal thinking, to some extent we have to be both liberal and conservative.

Not only do the two usually go hand-in-hand but elements of both are needed for electoral success.

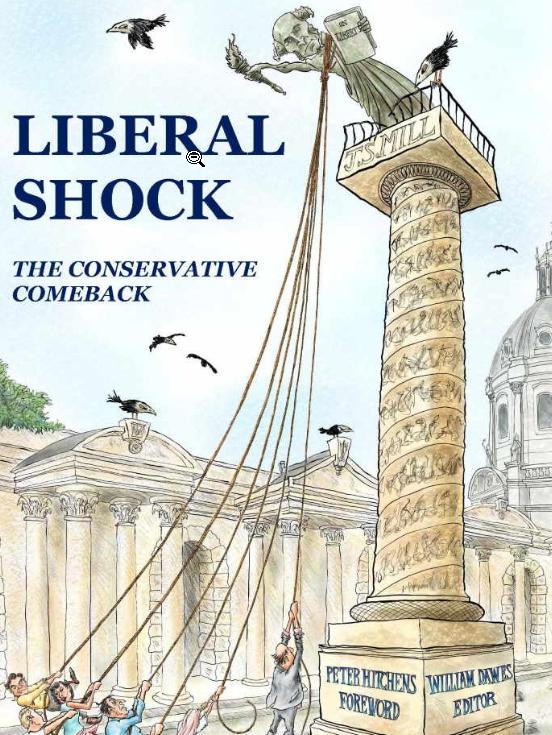

Tony Abbott is a former prime minister. This is an edited extract of his chapter in Liberal Shock: The Conservative Comeback edited by William Dawes (Connor Court), out now.

The Liberal Party does best when it focuses on creating jobs, making people’s lives easier and fostering pride in our country, not when it debates its own philosophy. It’s true, as John Howard recently said, that you can’t persuade if you don’t believe. But the Liberal Party has never believed in just one big thing. On some issues, Liberals are liberal; on other issues, Liberals are conservative — which is as it should be. At least in English-speaking countries, there’s been a warm embrace between liberalism and conservatism because so much of our history is the struggle for freedom; and also because true freedom cannot exist without an orderly society and a framework of law.