Trump may back-pedal but damage clearly done

Donald Trump could yet join the Kurds as a victim of the US hurried withdrawal from Syria.

In the first, American fighter jets and attack helicopters mounted a “show of force” against Turkish-backed militia moving towards a major US headquarters in northern Syria, even as the base’s occupants frantically packed up to pull out. This same militia, part of the Free Syrian Army, was sponsored by the US until 2015, allegedly under a CIA program. When that program ended, FSA came under the patronage of Turkey, which is of course a NATO country — meaning that these American aircraft were targeting troops trained, armed and paid for by the US, who were now working with a US ally.

In the second strike, aircraft bombed the same base once American troops had safely left, trying to destroy it to stop the headquarters, and a nearby ammunition dump and equipment stockpile, falling into the hands of Syrian troops rushing to occupy it.

The strike did not fully succeed: much of the base was left undamaged. One video clip posted by a Russian war correspondent highlighted the unseemly haste of the American withdrawal, showing an interior with a well-stocked kitchen, airconditioned sleeping areas, a game console, Wi-Fi routers, and an array of American snack foods and soft drinks. The US troops had “bugged out” at almost no notice, taking weapons and military equipment but abandoning their personal gear.

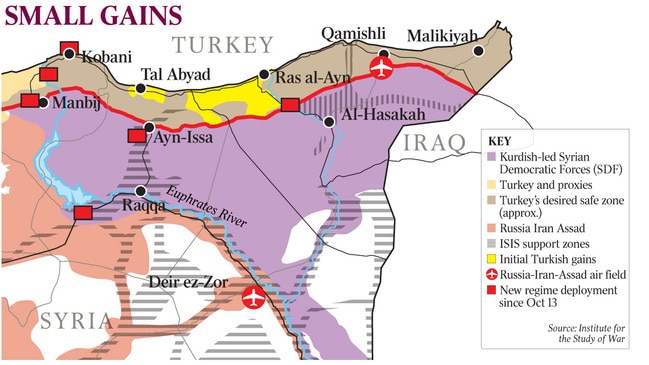

Russian and Syrian forces quickly occupied this and other US bases under an agreement with Kurdish leaders who, for almost two years, have been quietly negotiating with the Assad regime in talks brokered by Moscow.

The Kurds struck a deal with Damascus when they realised they could no longer count on US protection from Turkey. That deal — which effectively ended the Kurdish experiment in democratic self-government across their autonomous region of Rojava — saw Russian and Syrian troops fill the vacuum created by US withdrawal, reoccupying regions that had been beyond the government’s grasp for up to five years.

It was the regime’s most significant territorial gain since Russia’s intervention began in 2015, one that was all the sweeter for being virtually bloodless.

Russian military police in armoured vehicles are now patrolling an area between Turkish and Kurdish forces, while the formerly Kurdish-occupied city of Manbij is under regime control. Kurdish defenders, for now, continue to control the stronghold of Kobane. Russian and regime troops also moved into blocking positions designed to frustrate the Turkish advance, and seized key river and road crossing points. Their goal appears to be interdicting likely Turkish supply route and preventing Turkish-backed militia in the Afrin enclave (a Kurdish area in northern Syria that has been occupied by Turkey since January last year) from linking up with those taking part in the new operation. In the only other major region still outside regime control — the province of Idlib, in Syria’s northwest — Russian jet aircraft intensified their airstrikes and regime helicopters barrel-bombed civil and military targets ahead of a likely offensive designed to exploit the distraction created by the Turkish incursion further east.

Putin the big winner

The biggest winner here is Vladimir Putin in the Kremlin, closely followed by Bashar al-Assad in Damascus. Russia now is clearly in the driver’s seat, replacing the US as the military guarantor of any ceasefire, brokering talks among all major players including Turkey, and backing the Assad regime as it advances into every corner of the country. Iran and Hezbollah — Assad’s other main allies — have taken a back seat this week but are also undoubtedly pleased with progress, even as the war drags on into its ninth winter.

For their part, Turkish operations have had mixed results. As I predicted last week, the lightly equipped Kurds, lacking air defences, have been unable to manoeuvre in the open terrain of northeast Syria now that they can no longer call on US air cover. Kurdish columns on the move suffered heavily in Turkish artillery bombardments and airstrikes, while dug-in Kurdish defenders mostly held their own in the urban terrain of Ras al-Ayn and Tal Abyad. Turkey is now claiming control of Tal Abyad but local sources suggest there is still significant residual resistance in the town, with Kurds successfully counterattacking in some areas, recapturing districts lost in the initial onslaught and inflicting many casualties.

Turkish troops failed to capture Ras al-Ayn and were forced to bypass the town to the west. It still remains under Kurdish control, threatening the left rear of the Turkish-backed militia columns currently advancing towards the M4 highway.

The M4 is a main supply route that runs laterally across the full length of the Turkish front and connects several Kurdish strongpoints. The highway is key terrain, since whoever holds it can prevent an opponent shifting forces to reinforce threatened areas, while consolidating defences behind its raised roadway. The M4 is also Turkey’s declared limit of advance, forming the southern boundary of Ankara’s “safe zone” in northern Syria. But so far, despite claims to the contrary, Turkish forces have secured only two short lengths of highway, to the south and southwest of Ras al-Ayn. And at least two of the newly established Russian and regime blocking positions, created in the past few days, sit astride the M4, meaning that to secure the whole highway Turkey would need to fight Russia, Iran, the Syrian government, or all three. This seems unlikely, to say the least. At the same time, Turkish-backed militia in the M4 area triggered international outrage when they filmed themselves shooting Kurdish prisoners after tying their hands, then executing popular Kurdish politician Hevrin Khalaf and several aides after ambushing her convoy on the M4. Turkey has denied responsibility and the frontline phone-camera footage of the killings has not been independently verified. But it was enough to bring condemnation from the UN, the EU and the US congress.

Both houses of congress introduced legislation this week condemning Turkey and calling on Trump to reverse course. Senator Lindsey Graham, until recently one of the President’s most reliable allies, co-sponsored a Senate bill imposing sanctions on Turkey’s economy and on individual leaders including President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

The House of Representatives passed a resolution calling on Turkey to end its incursion, opposing the President’s decision to abandon the Kurds, and demanding that the administration “present a clear and specific plan for the enduring defeat of ISIS”.

This last point is telling, in two ways. First, the narrowness of congress’s demand is striking, in that it seeks a plan to defeat Islamic State rather than a strategy to stabilise Syria, then exit the region. The rise of Islamic State in 2014 did not occur in a vacuum. Rather, the “caliphate” was a side effect of regional instability triggered by the US-led invasion of Iraq, a premature coalition withdrawal before the country was stable, and the subsequent hijacking by Islamic extremists of the Arab Spring. Without a strategy to restore regional stability — which by definition must consider the interests and likely reactions of the Assad regime, the Kurds, Arab rebels, Syria’s neighbours including Iraq and Turkey, and, since 2015, Russia and Iran — merely defeating Islamic State would only create a vacuum that some combination of regional powers, their proxy armed groups or violent extremists was likely to fill.

Narrow goal

Preventing that outcome (or, worse, a resurgence of Islamic State) meant US forces had to remain in Syria. This was a recipe for permanent presence at best, chaotic withdrawal at worst. Even now, four years into a US intervention that has never been formally authorised by congress, US strategic decision-makers still seem unable to grasp the fact that the narrowness of their goal — defeating Islamic State at all costs, whatever the broader consequences, but then being unwilling to live with those consequences when they became apparent — helped to create the present crisis.

It was because of that narrow goal that successive US administrations supported, armed and trained the Kurds, our most proficient partner in fighting Islamic State on the ground, over the increasingly strident objections of a critical NATO ally in Ankara.

In doing so, US and coalition special forces achieved outstanding short-term military successes against Islamic State, at the cost of only eight American lives in the entire campaign since 2015 — a remarkable tactical achievement.

But at the strategic level they set themselves up for today’s contradiction, caught between two key allies who are bitter enemies, unable to leave lest they immediately attack each other. Trump’s decision to pull US troops out of the critical buffer zone along the Turkish-Syrian border may have triggered the immediate crisis, but its strategic roots go back at least to 2014.

Second, congress’s plaintive call for some kind of plan highlights the apparent lack of strategy on Trump’s part. Some in congress, who have long alleged collusion between Trump and Russia, claim to see a pro-Russia conspiracy here, given that Moscow is the main beneficiary of US withdrawal. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said as much in a fiery meeting on Wednesday that ended in her storming out of the Oval Office. Pelosi and Trump issued competing taunts in the media, each accusing the other of a “meltdown”. But the more likely explanation is mere impulsiveness from a President prone to shoot from the hip and ill-informed about a complex situation.

Domestic gamble

This lack of coherence has become especially evident since the resignation of defence secretary James Mattis, who quit over a previous, equally impulsive, Syria withdrawal plan late last year, and the more recent departure of national security adviser John Bolton.

Indeed, to the extent there was any method to the President’s Syria move, it may have been driven by domestic politics: the desire to make good on the election promise of extracting America from “endless wars” and to change the subject from impeachment and Ukraine, topics that have caused considerable angst in recent weeks.

Even on these terms, the withdrawal decision was a huge gamble, alienating a sizeable number of Republicans in congress, whose support will be crucial for Trump’s survival in the increasingly likely event he is impeached.

Two-thirds of house Republicans joined Democrats in voting for the resolution condemning Trump on Wednesday. Graham said on Thursday that had the same bill been put to the Senate, it would have passed by 80 votes.

Thus, at week’s end the President appeared increasingly isolated, even as he attacked opponents on Twitter, repeatedly shifted his justification for the Syria decision and made disparaging remarks about the Kurds, all while frantically back-pedalling — alternately criticising and threatening Turkey for taking actions he had approved only days earlier.

In this situation, the President’s decision to send Vice-President Mike Pence and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to Ankara to attempt to negotiate a ceasefire was an act of belated desperation. It is a testimony to the negotiating skills of both men that they emerged, late Thursday Ankara time, with a tentative agreement for a five-day pause in the Turkish offensive in return for suspension of additional US sanctions, and the removal of existing sanctions, as Pence put it, “once the ceasefire becomes permanent”. Trump hailed the agreement as an “amazing outcome” but Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu was quick to contradict Trump and Pence, emphasising in a joint press conference that this was not a ceasefire but an operational pause to give Kurdish forces time to evacuate the “security zone”, abandon or dismantle defences and heavy weapons, and withdraw south of the M4. Once that withdrawal took place, Cavusoglu insisted, the advance would resume in an orderly fashion to secure the entire security zone.

As this article went to print, US officials were insisting that Kurdish forces in the operational zone were retreating in compliance with the agreement, albeit reluctantly given that they had no other option. Under cover of darkness in Syria this could not be independently verified, but Kurdish and Syrian sources in the area suggested that a complete and peaceful withdrawal was unlikely, pointing to the active guerrilla campaign Kurdish forces had been waging against Turkish-backed militia in the Afrin enclave since it was occupied by Turkey.

In any case, even if the Kurds do retreat, key locations in the proposed security zone are now held by Russian and Syrian regime troops that are not party to the agreement: they have no incentive to withdraw and every incentive to consolidate their newly won advances. The regime’s deal with the Kurds still appears to stand so that the likelihood of Kurdish forces again partnering with the US-led coalition against Islamic State is highly uncertain. Russia, once again, with its powerbroker role now firmly cemented in the conflict, is likely to have the upper hand in any negotiation to follow.

This week on Fox News, commentator Dana Perino — who served as president George W. Bush’s press secretary at the height of the Iraq war — described America’s partnership with the Kurds as “tactical, transitional and temporary”. This is true, as far as it goes, and Trump has repeatedly expressed his preference for transactional relationships in all aspects of economic and foreign policy, including defence.

But a “transactional” relationship implies a two-way transaction, not a one-way street, and in this case the nature of transaction was clear from the outset. As senator Rand Paul put it in 2015, the Kurds would destroy Islamic State if Americans armed them and promised to support their aspirations for statehood: “I think they would fight like hell if we promised them a country.”

Now that Islamic State seems defeated for the moment, at least in a territorial sense, neither Paul (who vocally supports the decision to withdraw) nor Trump seem much inclined to honour America’s side of the transaction. Congress, using sanctions and the threat of impeachment, seems bent on reversing the President’s decision. But given a fast-moving, chaotic military situation on the ground in Syria — and the equally chaotic politics in Washington — it’s not clear that much, if any, of what has happened in the past week can be walked back.

Last week I wrote of the violent chaos that has overtaken northeast Syria since Donald Trump’s abandonment of America’s Kurdish partners, which enabled Turkey’s incursion into the area. Two airstrikes this week underline the extent of that chaos.