Trump and Harris are brawling all the way to an ugly climax

Despite the polls being maddening in their cross-grained complexity, they all indicate the contest for the Oval Office is exceptionally tight. With everything still in play and everything counting, this is how it could go.

There’s a vast range of possible outcomes, all of them unlikely. It could be the closest election since John F. Kennedy beat Richard Nixon by a whisker in 1960, amid allegations of vote rigging in Illinois. It might resemble George W. Bush v Al Gore in 2000. Bush lost the popular vote but won the electoral college, winning Florida by 500-odd votes, including 500 “hanging chads” and a 5-4 Supreme Court decision.

I wrote three successive front page pieces that night as the US TV networks called it first for Gore, then Bush, then realised it was too close to call. This election could be similarly tight but more explosive. A contradiction between the popular vote and the electoral college result could be stark. Anything could happen in response.

On the other hand, it might be orderly and clear cut, with the winner obvious.

The polls are maddening in their cross-grained complexity. But they all indicate the race is exceptionally tight. We’re still more than five weeks from November 5. There have been so many spectacularly unpredictable events already – two assassination attempts on Trump, Joe Biden standing down as a candidate. Everything is in flux. Virginia, Minnesota and South Dakota voting began on September 20.

Everything is still in play. Everything counts. Next week the vice-presidential candidates, Republican JD Vance and Democrat Tim Walz, debate on CNN.

It won’t be as important as the first presidential debate, which killed Biden’s candidacy, or Trump’s subsequent debate with Harris, which has seen a small advance for Harris in the polls. But given how tight the contest is, the vice-presidential debate could be consequential.

Given Trump’s age, 78, Vance has to show he can be president. Vance has proven an effective, sharp campaigner. Trump’s in danger of losing this election, which should be his for the taking, because he’s so undisciplined, his rhetoric so ragged and scattershot, against a stationary candidate wearing a big target – the profound policy failures of the Biden-Harris administration.

This campaign cries out for an effective professional politician. Enter Vance. He could prosecute the case against Harris far more effectively than Trump has. Trump suffered from high expectations against Harris. Harris benefited from low expectations.

The liberal media has pilloried Vance. It’s good for him to enter the debate as the underdog. Walz has almost as much of a problem with facts as Harris does. Vance could call him out in real time. Unlike Trump, Vance will be smart enough to prepare.

There won’t be 67 million people watching, as there were for Trump-Harris. But there will be tens of millions. If this election is as close as the last two, it could be decided by 100,000 votes in three battleground states, out of maybe 160 million voters nationally.

To see how this might unfold it’s necessary to understand how America elects presidents. Voting is not compulsory, so each side tries to persuade undecideds, but also tries to get its own supporters out to vote.

The election is democratic but not direct. US citizens vote for a presidential ticket, but they actually elect members of the electoral college, pledged to support one candidate or the other. The electoral college has 538 members. This number is reached by allocating every state the number of electoral college members equal to the number of congressmen it elects – that is, the number of its members of the House of Representatives – plus two because every state gets two senators.

Every state’s House of Reps numbers are based on population. Thus California has 40 million people and gets 54 electoral college votes, for its 52 congressmen and two senators. Wyoming, with a population of about 600,000, gets three electoral college votes, two for its senators and one for its single congressional district. Every 200,000 people in Wyoming get an electoral college representative, whereas it’s nearer to one electoral college vote for every 750,000 people in California.

This is not undemocratic and doesn’t much distort results. Every federal system has some measure of small-state bias. In Australia, Tasmania, with a smaller population than Wyoming, elects 12 senators, the same as NSW with eight million people.

The small-state bias helps Republicans, but not grossly. The Democrats win the biggest state, California. Republicans win numbers two and three, Texas and Florida. The Democrats win the fourth biggest, New York.

In the last congressional election, in 2022, Republicans won fewer seats than their percentage of the vote. The small-state bias is less distorting than a party just winning huge margins in its safest districts.

All states, except Nebraska and Maine, allocate electoral college votes on a winner-takes-all basis. Nebraska and Maine each give two electoral college votes to the candidate who wins the state overall and allocate the rest of their votes on the basis of who won each congressional district.

It’s possible for Harris to win one electoral college vote from Nebraska from one congressional district even as the state votes overall for Trump. And it’s possible for Trump to win one electoral college vote from Maine in one congressional district even as Maine votes for Harris overall.

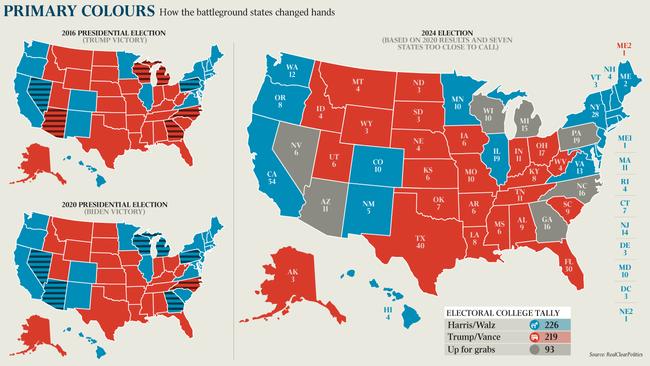

For the past three elections, there have been only the same seven battleground states in play. These are, in order of electoral college vote size: Pennsylvania (19), Georgia (16), North Carolina (16), Michigan (15), Arizona (11), Wisconsin (10) and Nevada (6).

A glance at the US electoral maps accompanying this article demonstrates not only the electoral college’s arithmetic but the deep cultural structure and divisions of America. Democrats almost always win the west coast, the so-called left coast, and the liberal northeast coast. The Republicans win all of the old south except Virginia, and most of the Rocky Mountain and prairie states. The mid-west and the Great Lake states are a mighty battleground, mainly in Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania.

The mid-west is more conservative and more religious than the coasts. It requires colossal ignorance of America to regard the mid-west as crude or unsophisticated. It’s courtly, traditional and friendly. The University of Chicago has produced more Nobel prizes than any other university. The first skyscraper was built in Chicago. The mid-west spawned a magnificent, utterly distinctive American literary culture. It’s the heartland, still.

These solid voting patterns are the electoral illustration of deep cultural differences, many would say polarisations.

Americans are increasingly sorting themselves out so they live and work, take leisure and, if that’s their thing, worship among people just like them. Not necessarily racially just like them. Progressive politics is obsessed with race but ordinary people much less so. Rates of racial intermarriage are very high.

But culturally and ideologically, religiously or anti-religiously, people want to live with other people like themselves. As far as possible they live in streets, neighbourhoods, towns, cities and states that embody their own cultural and political preferences.

This social sorting was first elucidated in Charles Murray’s brilliant 2012 book, Coming Apart. Red states are generally more successful in economic policy than blue states.

That is, the liberal Democrat states – which are all in on high taxes, maximum renewable energy, ultra-progressive education fashions and pro-union – like California are losing people and businesses to red states such as Texas or Florida that use fossil fuels as well as renewables, are lower tax, anti-union, more traditional in education and so on. California is losing people to Florida and Texas. The people it’s losing are conservatives. So California becomes more liberal, Florida and Texas more conservative.

A “safe” state could always surprise everybody and flip in November. But there’s no indication this is likely.

When Trump was leading Biden so convincingly, especially just after Biden’s disastrous debate, it looked as though Trump could take Virginia, with its 13 electoral college votes, or New Hampshire, with its four. But they’ve moved safely back to Harris. People speculate about Virginia and New Hampshire every cycle, but they don’t change. So, without allocating any electoral college votes from the battleground states, assuming all other states vote as they did in 2020, and giving Harris one electoral college vote from Nebraska and Trump one from Maine, the numbers start out with Harris at 226 and Trump at 219. That’s a slight advantage to Harris. To get to 270, she needs 44 from the battleground states, Trump needs 51.

If Harris wins just the three Great Lakes states, Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, she gets exactly to 270. Trump could win all four of the other battleground states, which would yield him 49 electoral college votes and leave him short at 268.

That is perhaps Harris’s most likely path to the Oval Office. Trump’s most likely path would be to win Pennsylvania, Georgia and North Carolina. These three states would yield 51 electoral college votes and put Trump over the top at exactly 270. Harris could win the other two Great Lakes states, and Arizona and Nevada, and come up short at 268. That is probably Trump’s most likely path back to the White House.

Trump can’t win without one of the Great Lakes states. Typically Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania are so much alike they vote for the same candidate. However, electoral politics is not the common law. It’s not bound by precedent. Trump seems to be doing just a bit better in Pennsylvania than in the other two states. Given how tiny some state margins have been in recent elections, Trump may detach Pennsylvania from its regional brothers.

Trump looks strong in Georgia and North Carolina.

However, Trump or Harris could follow unpredictable paths to the White House. Trump could steal Wisconsin, as he did in 2016, lose the other Great Lakes states, but win North Carolina, Georgia and Arizona, where he’s also looking strong.

Harris could lose Pennsylvania, win the other Great Lakes states, take Georgia which, with its strong black population, Biden won last time, and Nevada, where she’s currently ahead, and that puts her over the top.

The polls are deeply confusing and not definitive because they’re so close. But it’s worth getting a sense of them. The RealClearPolitics poll average puts Harris 2 per cent ahead on the popular vote. But it has Trump 0.1 per cent ahead overall in the battleground states.

Nonetheless, when it configures an electoral map with all states allocated on the basis of polls today, it has Harris securing the narrowest of victories, 276 to 262. It gets there by giving Harris all three Great Lakes states plus Nevada.

The RCP folks would be the first to say their poll average is not a prediction, just a very limited snapshot with a margin of error bigger than any candidate’s lead. And it’s contradicted by other polls. CNN’s latest poll has a dead heat among registered voters, and Harris with a 1 per cent national lead among likely voters.

Here’s another thing. At the last presidential election in 2020, which Biden won convincingly, the polls nonetheless underestimated Trump’s vote by more than 3 per cent.

In 2016, when Trump won unexpectedly, the polls underestimated Trump by 2 per cent.

If the polls underestimate Trump by as much as they did in 2020, Trump could win all the battleground states, giving him a 312 to 226 electoral college margin. He could even win the national popular vote. And it’s quite possible the polls underestimate Trump by even more.

Why do polls underestimate Trump? Some voters don’t like Trump personally and are embarrassed to say they support him – shy Trumpers; others have lifestyle patterns that make them hard for pollsters to reach.

On the other hand, poll companies will try to correct their past bias. In the 2022 congressional elections polls underestimated the Democrat vote. If the polls are underestimating Harris by, say, 2 per cent, she wins the popular vote, all the battleground states and 319 to 219 in the electoral college.

Most fun of all, there’s a real statistical chance Trump and Harris could tie at 269 each. That would see the election decided by the House of Representatives. It would be done by the newly elected house and each state gets just one vote. The Republicans are in the majority of states, so probably Trump wins.

But in any state where the result was close there would surely be desperate court challenges and the like. If Harris won the popular vote convincingly but lost in a tie resolved in the House of Reps, all hell would break loose. The violent Black Lives Matter and defund the police demonstrations of 2020 would look like a picnic.

A final wrinkle is that the vice-president in such circumstances is chosen by the Senate, where Democrats have the majority. You could just possibly get Republican president Trump and Democrat vice-president Walz.

Most polls, however, expect Republicans to take control of the Senate, at least 51 to 49, after picking up seats in Montana and West Virginia.

Harris is polling well behind Biden at this stage in 2020 or Hillary Clinton in 2016. She has slowly been improving. Trump is so undisciplined in his rhetoric that he can’t seem to find his line and length to make her pay politically for the dismal record of the Biden-Harris administration.

Trump has declined in his own performance. He was once brutal but brilliant with nicknames. “Crooked Hillary” captured something of people’s feelings about the money-grubbing Clintons. Calling senator Elizabeth Warren, who claimed Native American ancestry, Pocahontas so messed with Warren’s head, she took a DNA test that revealed she had even less Native American ancestry than the average Caucasian American. Trump has nothing similar for Harris.

Neither Trump nor Harris is offering any coherent, sustainable policy proposals. At the level of policy, it has been a shockingly bad campaign from both sides.

The election is probably still Trump’s to lose, and he seems to be losing it. He’s actually pretty good at losing elections.

Harris looks an insecure politician, apparently suffering impostor syndrome, which is perhaps why she won’t do a press conference. But, with Barack Obama and his machine behind her, she’s being effectively managed. On the polls, she’s a bit behind where Biden was with African-Americans and with Hispanics. Indeed, Trump is registering support of 40 per cent of Hispanics, more in battleground states.

Bizarrely, because Harris was so invisible as Vice-President, while Trump has dominated American politics, in office and out, for eight years, Harris looks like the change agent. Some polls have Trump ahead nationally, but more favour Harris slightly.

Whoever loses is going to be mighty unhappy; so are the social forces behind them.

When I was a kid, in one of my favourite TV shows, the great Sam Menacker used to announce each week: “This is World Championship Wrestling, where anything can happen and probably will!”

No, no. This is American politics.

Donald Trump versus Kamala Harris. It’s a political NRL grand final that is already a draw. We’re now in golden point. Even this mightn’t be decisive. This election could end up with the umpires, in the US House of Representatives, or the Supreme Court. Or, ugliest of all, in the streets.