In recent weeks we’ve seen the body-count of traitors against the People’s Republic of China pile up.

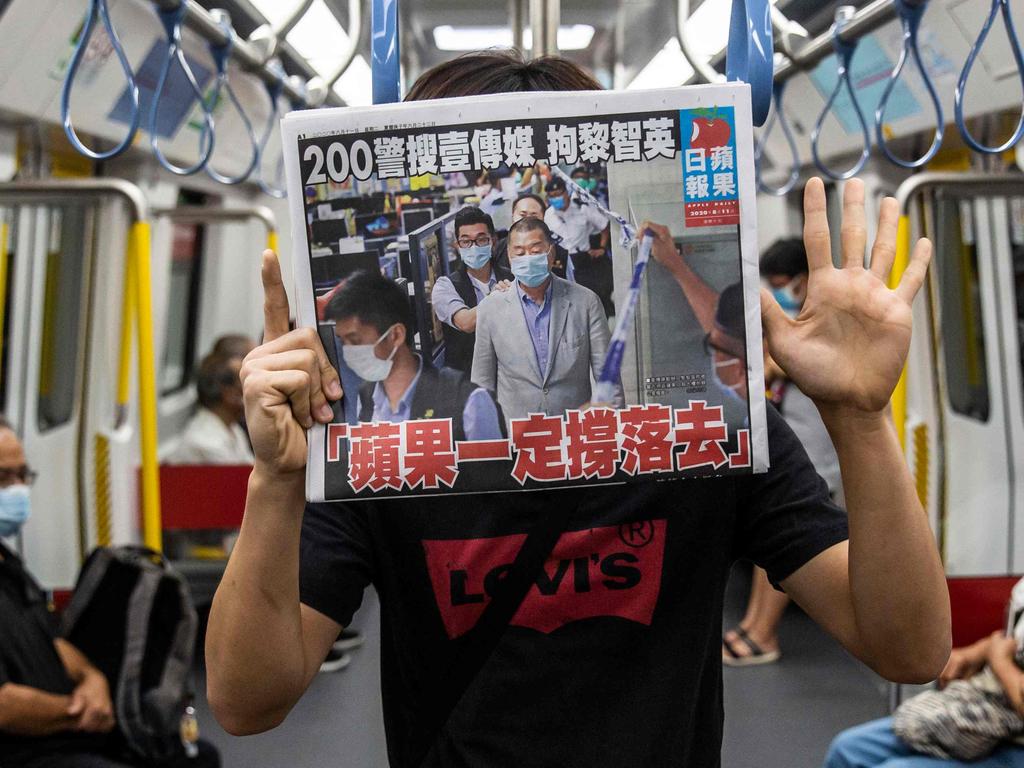

Hu Xijin, the often-agitated editor-in-chief of the Global Times, wrote that Jimmy Lai, the founder and publisher of Hong Kong’s most-read paid-circulation newspaper Apple Daily, “has become a 100 per cent traitor”.

Lai left the PRC as a child for Hong Kong, and made a fortune in founding the Giordano clothes chain, before switching to media and becoming globally famous as an articulate critic of PRC governance. Hong Kong, he told me in an interview a few years ago, “is now my home; it’s where my heart is. They leave me alone there.”

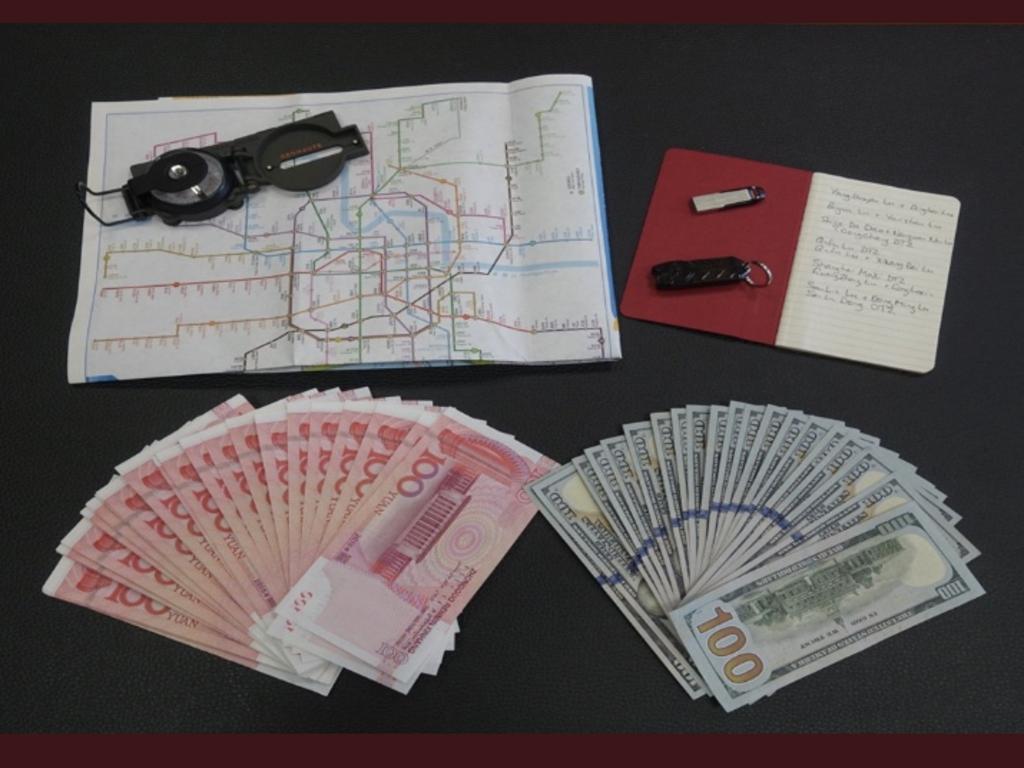

Not any more. Hu made his accusation after Lai had been arrested under the draconian new National Security Law imposed in Hong Kong by Beijing.

His “treachery” appears to have comprised sharing with leading American politicians his concerns about the then looming threat to the long-established freedoms and rule of law in Hong Kong, the home that had earned his trust.

Last week we saw the PRC’s deputy ambassador Wang Xining compare Canberra’s advocacy for an international inquiry into the origins of COVID-19 with the treachery of Marcus Junius Brutus against his friend and mentor Julius Caesar, who was assassinated on March 15, the Ides of March, 44BC.

Wang cited Act 3, Scene 1 of William Shakespeare’s tragedy. The stage direction tells the accusers to stab Caesar, whose final words are: “Et tu, Brutè? — Then fall Caesar.”

The well-read diplomat spoke of “this shocking news of a proposal coming from Australia, which is supposed to be a good friend of China” as akin to Caesar spying his protege among his assassins.

The sentiment that Wang sought to arouse is eminently understandable. What kind of a person would betray a friend in such a violent way? But the setting around this famous scene immensely complicates what would seem straightforwardly reprehensible treachery.

Caesar had not long before ordered the senate to make him dictator for life. A dictator was a magistrate who usually ruled during a brief time of emergency. His enthronement — the words kaiser and tsar derive from Caesar — did indeed trigger the end of Rome’s long-successful republican governance, which Brutus and co had sought to restore, in vain as events transpired.

Using this episode as a metaphor for Australia-China relations risks rebounding.

The next line after Caesar’s demise in Shakespeare’s play has Cornelius Cinna cry out: “Liberty! Freedom! Tyranny is dead!”Gaius Cassius Longinus, Brutus’s brother-in-law, then builds on that formula, celebrating: “Liberty, freedom, and enfranchisement!”

In 2018 the PRC’s paramount ruler Xi Jinping had China’s legislature amend the constitution to permit him to remain president for life, a move that even now is perceived by some party members as betraying the republic’s core values. Freedom and enfranchisement are not prime qualities of life in today’s PRC.

This week it was revealed that one of the best-known and liked Australians living in China, the TV presenter Cheng Lei, has been detained in a secret location for unknown reasons, under a catch-all regulation intended to counter “endangering national security”.

Canberra’s travel advice to any Australians who may be able to enter China rightly now includes that: “Australians may be at risk of arbitrary detention.”

The record of arrests of Australians in China — including Stern Hu, Matthew Ng, Charlotte Chou, and the writer Yang Hengjun, detained since January 2019 — shows that those of Chinese ethnicity are at greatest risk.

The Chinese Communist Party tends to hold that all “sons and daughters of the yellow emperor”, as it dubs anyone of Chinese heritage, should display a primary loyalty to the PRC, regardless of nationality.

This week China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi described the visit of the Czech Republic’s Senate President Milos Vystrcil to Taiwan — whose citizens have never lived under PRC rule — as “an act of international treachery” for which he will “pay a heavy price”. This may have been a mistake. The Czechs know something of communist rule.

The problem with wheeling out the “treachery” gun so often is that it triggers the questions: who is expected to be loyal to whom, and why? Trust must be earned, and like accountability, only works effectively when it is mutual.

The question also naturally arises as to what is the “China” that is arousing so much treachery? The multiethnic ancient civilisation? The land, now occupied by the PRC, that once embraced many kingdoms and tribes? The “Han” Chinese culture that drives today’s sinification of religions and ethnic traditions? The 71-year-old PRC itself, with ideological roots in Marxist-Leninism, and rituals that originated in the Soviet Union?

Mutual loyalty is indeed better than stabbing each other in the back. But it can’t be commanded.

Rowan Callick, twice a China correspondent for The Australian, is an Industry Fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

Treachery is a tricky substance. If one starts noticing too much of it around, then the crime — the worst in the book, according to most legal codes — turns around to bite the accuser. With so many traitors around, maybe it’s the accuser who’s the problem.