The larrikin and the giant: how Australia and China fell out of love

China’s problems with Australia go far beyond the Liberals’ last three leaders. To understand where it all went wrong, you have to go back to the election of Mandarin-speaking Kevin Rudd.

It is often said that liberal democracies do not understand China as well as China understands them.

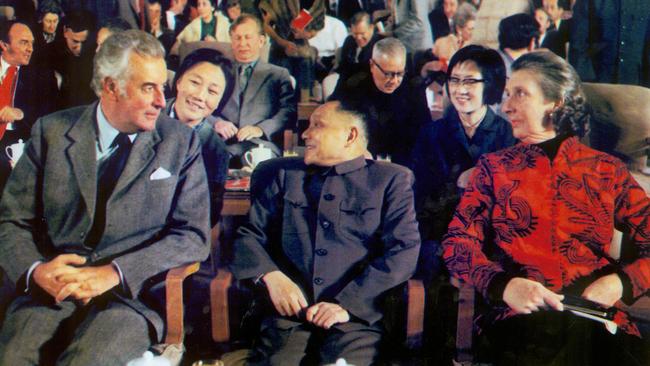

That was likely true for Australia back in the Hawke era, during the infatuation stage of the relationship. And it still held during the promiscuous Howard era.

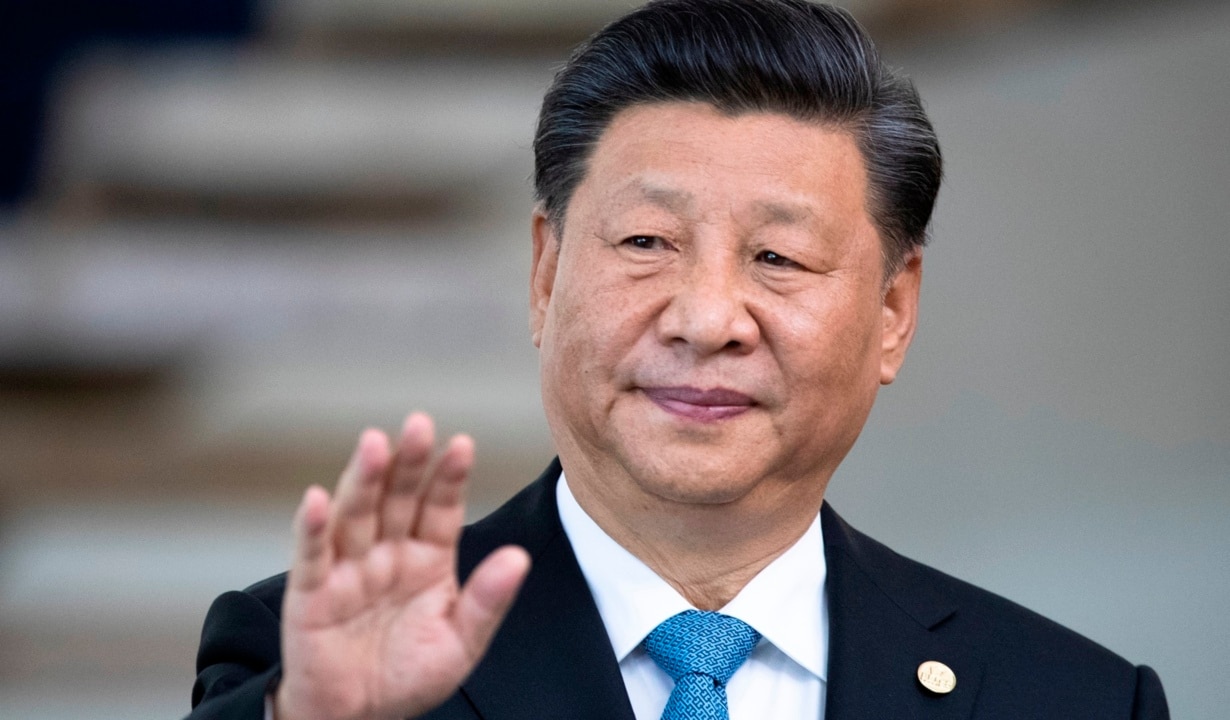

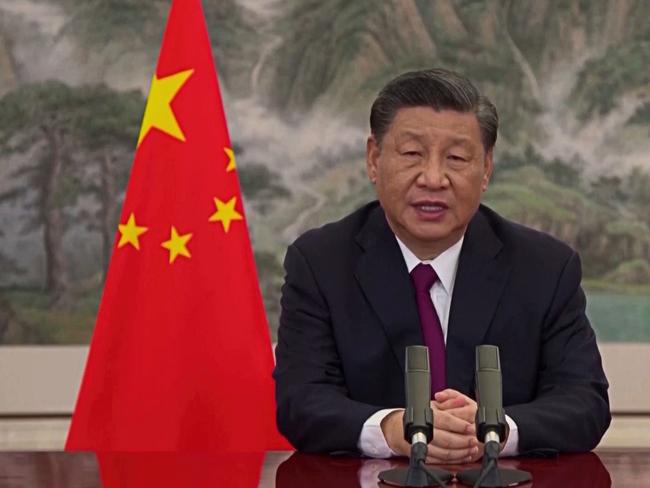

But it is not a convincing explanation for many of the ruptures since December 2007. Since then, the problem may almost be the reverse: that Canberra has understood Beijing too well. Right now, it is Xi Jinping’s China that looks thoroughly confused.

To better understand where it all went wrong – a crucial exercise as the Albanese government attempts to stabilise the relationship – you have to go back to Kevin Rudd.

No prime minister had assumed the job with anything like the profile in China of the former first secretary of Australia’s embassy in Beijing. “Ruddmania” spread across Australia’s biggest trading partner after the then leader of the opposition, in September 2007, addressed visiting Chinese president Hu Jintao in Mandarin. It went into overdrive when, only three months later, the man known to most Chinese as Lu Kewenbecame Australia’s 26th prime minister.

“The euphoria did not last long,” Yi Wang, who briefly worked in the Chinese foreign ministry and now is based in Brisbane, writes in a masterful survey of what has gone wrong in the Australia-China relationship.

Rudd’s visit to China in April 2008 set off alarm bells in the Communist Party’s leadership compound, Zhongnanhai. In an extraordinary speech to an audience at Peking University, the most China-literate leader of a G20 country – a record he still holds – attempted to create a new framework for Australia’s relationship with East Asia’s rising giant.

“A true friend,” Rudd said, speaking in Mandarin, “is one who can be a zhengyou, that is a partner who sees beyond immediate benefit to the broader and firm basis for continuing, profound and sincere friendship.”

It was a brazen cross-cultural attempt to encourage China to be a “responsible global stakeholder”, the engagement-era phrase coined in 2005 by US deputy secretary of state Robert Zoellick.

The Australian prime minister brought up human rights issues in Tibet, in Mandarin, in front of an audience at China’s pre-eminent tertiary institution. This was a frightening development.

“His Chinese hosts began to doubt whether this Sinologist was quite the Sinophile for whom they had hoped,” observes Wang, now a scholar at Griffith University, in his illuminating essay, The Larrikin and the Rising Giant.

Wang – who was an official Chinese translator when he first met Rudd in Beijing – marks that episode as the beginning of Australia and China’s ”estrangement”.

That assessment is a break with the official line in China, which marks the origin of the troubles with prime minister Malcolm Turnbull a decade later. It is also a useful corrective to often partisan accounts in Australia that obsess over the Turnbull and Morrison governments.

Speaking from his home office in Brisbane after Inquirer eventually coaxed him into an interview, Wang says that characterisation is not fair. “Turnbull is no Sinophobe at all, as some portray him,” Wang says.

Neither, of course, was Rudd – but still the points of friction piled up fast: curbs on Chinese investment in Australian iron ore giants; the arrest of Rio Tinto mining executive Stern Hu; accusations about Chinese cyberattacks; the controversy around defence minister Joel Fitzgibbon’s financial relations with a Chinese-Australian business woman; the Rudd government’s seminal 2009 defence white paper, which implicitly identified China as a threat to regional stability; and the presence at a film festival in Melbourne of Rebiya Kadeer, whom Beijing accused of being involved in violent riots in Urumqi in Xinjiang.

Beijing’s response?

“To register its displeasure, Beijing suspended high-level contacts with Canberra,” writes Wang, who before going into academe worked as a journalist at the BBC and an executive at SBS.

The Howard government had been given the same treatment a decade earlier after a volley of disputes. The Turnbull government’s stint in the freezer came in late 2017. After a brief reprieve, it was the Morrison government’s turn after another cluster of trouble, culminating in its April 2020 call for an independent inquiry into the coronavirus.

Perplexed by pluck

This has been a big week in China’s Australian studies community, a vital conduit between the two countries. The diplomat turned esteemed Australian scholar Yi Wang – or Wang Yi to his Chinese audience – has finally had his essay published in China.

There it was in the Chinese version of Monday’s Global Times, the country’s highest selling newspaper, with the headline: “Australian scholar Wang Yi: Canberra’s ‘Larrikin’ mentality hurts Australia-China relations”.

It had been translated by a scholar at Wang’s alma mater, Beijing Foreign Studies University, a feeder university for China’s diplomatic corps and an institution that has done more than almost any other to help the country talk to the world.

The piece that ran in the Chinese party state masthead was much shorter than the original English version, which had been published eight months earlier in British academic publisher Routledge’s Far East and Australasia 2022. The reference book now sits in university libraries around the world. But even in its truncated form – despite the cuts and contortions required to pass Beijing’s censors – here was the best account on the implosion of the Australia-China relationship to be published in Chinese.

Unlike endless other accounts published in party state media, this finally acknowledged Australia’s resilience. “Despite the multiple trade sanctions applied by Beijing, Canberra still had a trump card in its trade repertoire,” the Australia-China expert explained. “The biggest and most lucrative item of Australian exports – iron ore – was a commodity on which China’s infrastructure projects depended.”

The Chinese essay also outlined, as the English version does so convincingly, how China’s problems with Australia go far beyond the Liberals’ last three leaders, Turnbull, Scott Morrison and Peter Dutton. It marked the estrangement as starting 15 years ago with the election of a Chinese-speaking Rudd, who as a teenager had idolised Gough Whitlam. That observation was a jolt to many in China’s Australian studies community.

Wang is an immensely gifted translator who can recite passages of Shakespeare and then switch to perfect Mandarin to pluck a comparative phrase from the Chinese classical canon.

He is also so allergic to publicity that I have to confess to spending some of this week unsure whether the Chinese diplomat-cum-Australian scholar was a real person rather than someone’s pen name (admittedly an odd choice, as it shares the same two characters as China’s Foreign Minister).

After confirming his existence over email, the scholar tried repeatedly to rebuff my requests for an interview. Eventually, he agreed to speak – but only after a few more polite refusals.

“I almost got cold feet earlier because of my inclination to keep a low profile rather than attracting attention and the spotlight,” he says. Wang’s obvious pain at the state of the bilateral relationship – his area of expertise and the backdrop to much of his life – eventually changed his mind.

His translated essay was an attempt to do something similar. In the process, it made history by introducing the Australian term larrikin to a Chinese audience. It is a phrase with no good counterpart in Chinese. The translator’s dilemma was to convey the positive quality the term has to an Australian ear while retaining its mischief.

“I really racked my brain,” he says, recalling other translations he had tried and abandoned before finding the right harmony of sound and meaning. Eventually, he settled on Lai rui qing. “I hope it will catch on,” he says.

The novelty of the word helped convey Beijing’s astonishment at uppity Australia’s behaviour since 2007. “(China) has at times been stunned by the boldness of the larrikin’s actions, not realising that some of these actions might have been motivated by anxieties over the rising giant’s posture and intentions in rushing to rise to its feet,” he explains in one of the most enlightening sentences ever to be published in Global Times.

Here was one of the key dynamics in the now troubled relationship being explained with rare freshness to a Chinese readership. Australia had been unnerved by China’s assertive behaviour as it grew more powerful – and China had been perplexed by Australia’s plucky response.

What made this country of 25 million people, slightly more than half the size of the average Chinese province, behave like this? The novel word Lai rui qing helped bridge the gulf.

Beijing’s censorship

The problems in the Australia-China relationship go far beyond translation. China’s stupefying censorship regime is a huge impediment. Compare the original version of Wang’s essay with the pruned Chinese account that was allowed past the censors.

In the original, Beijing’s deadly crackdown in Tiananmen Square in 1989 ended the Hawke era’s romance. In the Chinese version, that epochal rupture is reduced to a single, stifled sentence: “In the late 1980s, the Australian government participated in condemnation of the Chinese government.”

Rudd’s speech at Peking University, the event that marks the beginning of the ongoing estrangement era, is removed entirely. The lists of hot issues that confronted John Howard, then Rudd, then Turnbull, then Morrison are all jarringly cut.

They never had a chance against the censors, as they read like the lists of dangerous terms issued to Chinese newsrooms: the Taiwan Strait crisis, protests in Tibet, Uighur separatists, United Front scandals, Chinese hacking operations, political repression in Hong Kong, the detention of Australians in China, and on and on.

With such stunted information, it is little wonder so many in China are so confused about Australia’s behaviour.

Also entirely absent in the Chinese account is President Xi Jinping. He is a pivotal figure in the English version, as he must be in any honest history of the relationship.

“As China’s economy grew stronger, the moderate style of Hu Jintao’s administration gave way to the more strident leadership of Xi Jinping,” Wang writes. “Xi’s anti-corruption campaign and subsequent abolition of presidential term limits helped to consolidate his power domestically, but his government’s international stance, especially over the South China Sea dispute, as well as a pattern of feisty behaviour that came to be dubbed ‘wolf warrior diplomacy’, caused concern among various countries, including Australia.”

Not a word of that makes it into the Chinese version.

The biggest tragedy comes right at the end, which asks: “Will this estrangement lead to a total rupture of the relationship? Or will the current stoush give way to a new lease of life?

“Therein lies a test of the wisdom of the leadership on both sides. If history is any guide, such leadership could benefit from Whitlam’s fortitude and foresight on the Australian side and Deng’s pragmatism and open-mindedness on the Chinese side,” Wang concludes – or at least, that’s how he does in the original.

The final sentence in the Chinese translation was simply: “If history is any guide, Australia can learn from Whitlam’s courage and vision.”

Censors in Beijing today would not dare let the original through, with its mention of Deng Xiaoping, the leader who opened China to the world and who warned about the perils of personality cults and lifelong terms. It is all far too sensitive with Xi now months away from embarking on his precedent-breaking third five-year term.

What comes next?

“Modern Australia is unimaginable without the talented and dynamic contribution of Australians of Chinese descent,” Turnbull said in a speech on the bilateral relationship delivered just weeks before he lost power.

Those 1.2 million citizens are a “vital thread in the fabric of Australian society”, as Turnbull said; but many have not always felt that way as Australia and China have become more estranged.

That partly explains why an Australian with the amazing background of Wang – who as a diplomat, journalist and researcher has spent time with the most senior leaders in both China and Australia – has until now barely said a word in public on the sad state of affairs.

The foreign interference legislation that the Turnbull government passed in 2018 was not the start of the trouble but it was a turning point.

“Since the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1972 China had been a country to be worked on; however, with the adoption of the foreign interference legislation, China became a country to be guarded against,” Wang observes.

There were good reasons for Turnbull, the grandfather of two Australians with Chinese-heritage, to introduce that legislation.

But we should be careful that we don’t let legitimate concern about malign foreign interference stigmatise one of Australia’s greatest assets: our Chinese heritage community.

We incorrigible larrikins will need to stick together in the years ahead.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout