To understand our history, students must delve into colonial past

The problem is simple. It is impossible to understand this country’s history without understanding its colonial origins: but the only aspect of pre-20th century history that will have to be taught is colonisation as it affected Indigenous Australians.

So limited a perspective cannot even make sense of the Indigenous experience. That experience was not a story in black and white; it was one of interactions that varied greatly, both geographically and over time.

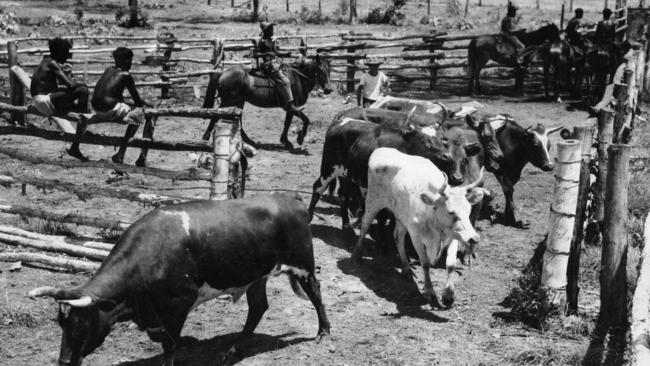

Aboriginal stockmen, continuing to live on their own traditional country while being “born in the cattle” in the Northern Territory’s vast stations; Christian converts to evangelical faith on the Maloga Mission near the Murray River, acquiring literacy to propel their own lives (as literacy did for William Cooper, one of the earliest campaigners for Aboriginal rights in the 20th century); Queensland Native Police conducting sorties and killing raids in the colony’s remote regions – all of those experiences, along with many others, defy any ideological reduction of this continent’s colonial history to a straightforward clash between Indigenous people on one side and settlers on the other.

At the same time, given how restricted the compulsory component of the curriculum is, many students may never be adequately exposed to the momentous developments that, over the course of the 19th century, defined the bases of today’s Australia.

In effect, by 1901 essentially all the tools of our current-day democratic life had been put in place. The rule of law arrived on the First Fleet and was underscored when a teenage convict couple sued their ship’s captain for stealing their luggage, and when Governor George Gipps insisted on a retrial to properly secure justice after the Myall Creek massacre in 1839.

Meanwhile, a combatively free press and the freedom of association prepared the ground for colonial self-government, which almost immediately began the largely untried experiment of mass suffrage democracy. And at the end of the 19th century a constitution was designed as the foundational law of nationhood and put to the voters at plebiscites for approval.

Overall, the style of life, the pace and rapidity of information exchange, attitudes to race and the roles of men and women may have transformed dramatically since then, but the democratic processes with which we try to solve our problems are essentially the same as those Vida Goldstein, Alfred Deakin and then Cooper deployed to effect change.

Without having studied those developments, and the pressures that drove them, students will be utterly unable to understand the history of 20th-century Australia when they get to it later in their schooling. They will therefore be left with a disjointed set of facts and insights that lack the continuity that is a central feature of history, properly taught.

But the damage will not only be to students’ knowledge of their country’s story. It will also affect their capacity to act as informed citizens. In 2016 all the state education ministers signed the Statement of Learning for Civics and Citizenship, which agreed that civics would be taught to all Australian school students with an historical perspective.

Underpinning that statement is the belief that a solid grasp of the evolution of this country’s institutions is not merely a form of respect for the past – it both helps guide a sense of why things are as they are and provides students with examples of how they have been and can be transformed.

That idea is not new. It was at the heart of the intentions of the legislators and educators who created state and nationwide schooling in the colonial era. They were convinced that the purpose of education in a society trying the experiment of democracy was not purely to ensure its members were literate and numerate; it was to prepare today’s young people to be the self-aware citizens of tomorrow, capable of participating in and where necessary changing life in their nation.

They knew the challenges of binding people of different national origin, different religion, different classes, together into one community were existential. They saw education as the key to its resolution. This is why they placed so much priority on access to schooling. When the colonies achieved self-government in the mid-19th century their education systems lagged badly behind those of Canada and the US; but within three decades they had propelled them to the forefront. Schooling was provided that was compulsory, free and secular, meaning that all faiths, all social classes could send their children to the state’s schools, making education one of the key cradles of the egalitarian ethos that has marked Australian life.

By the beginning of the 20th century the civic purpose of schooling had also begun to penetrate the actual curriculum. A new education reform movement emerged, preoccupied with making sure that not just the close associations of childhood would encourage a more closely bonded community but that civics should be taught explicitly.

This meant less cramming of dates enumerating the successive reigns of different kings and queens, and more focus on using history to equip citizens for life in a democratic nation.

In 1905 Frank Tate, the Victorian director of education and civics reformer, declared that all students deserved to have “an intelligent knowledge of, and appreciation for, our leading national institutions, so that they may be consistently maintained, and, if need be, stoutly defended”.

Eight years later he reported to his government minister defending the use of history in schools to prepare the citizens of the future.

“Knowledge of dates or of events in a given king’s reign may have been more accurate in schools 10 or 20 years ago,” Tate acknowledged, but “the pupils today have a better idea of the movements which gave us our present-day freedom and the teaching is better designed to make them useful citizens”.

Tate was persuaded by a reasoning first identified by Montesquieu 200 years earlier, in The Spirit of the Laws. Whereas hierarchical societies depend on status, prestige and honour to maintain themselves, and despotism depends more purely on fear, democracies depend on a far flimsier reed – civic virtue. And the only way a democracy can build and protect civic virtue, Montesquieu said, is by bringing “the whole power of education” to bear in the formation of its citizens. Nothing else will ensure this – and not even that is guaranteed.

It is obviously difficult to measure the success or otherwise of the early decades of Australia’s civic-history education experiment and any assessment must be subject to myriad qualifications.

But the vigour of Australian democracy, and the strength of the faith in its institutions, offer themselves as indirect evidence.

Consider the searing controversy that polarised Australians during World War I. Two national plebiscites were held to establish majority opinion on the question of conscription – compulsory enlistment for fighting-age men in the armed forces. What is generally emphasised in accounts of these referendums is the degree of violent divisiveness that threatened to immolate the national debate during the campaigns leading up to voting, and this cannot be underplayed.

Yet obscured in that is the sheer fact of the monumental democratic achievement. Just as the people of Australia had gone to the polls to decide on whether the Constitution be approved and the nation properly begun in 1901, now a nation involved in the all-consuming global conflict of the Great War resolved the question of conscription not by presidential decree, imperial diktat or war cabinet decision but by putting the question to the people.

No other nation even considered such an extraordinary procedure in the war. It reflected a confidence in democracy we can only envy.

Today, with so many factors tearing the country apart, rekindling the ethos of democratic citizenship should be a priority – and that requires a history curriculum that is free of ideological blinkers, is comprehensive and, most of all, capable of stimulating young minds.

We know that history teachers love the practice of history, and deeply respect the discipline it insists on. They are proud of their training, and prize the discipline’s emphasis on weighing up different perspectives, different accounts. Their genuine preference is to introduce students to a genuine diversity of perspectives.

Yet under this draft curriculum the encouragement of genuine debate, in the pursuit of as grounded, intelligent and truthful account of the past as possible, as part of a wider attempt to better understand ourselves and how we came to be, goes by the wayside.

Unfortunately, the draft’s many defects cannot possibly be adequately identified, and viable remedies proposed, in the incredibly scant two-week period that has been granted for submissions. And we are deeply troubled by aspects of the process, such as the seemingly inexplicable fact that the submission of the History Teachers Association of NSW is shrouded in secrecy.

Writing 100 years after Montesquieu, and in the newly inaugurated self-governing republic of the United States, James Madison had no doubts about the importance of these issues. “A people who mean to be their own Governors,” he said, “must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.” A popular government that didn’t have this foundation of civic knowledge, he concluded, “is but a prologue to a farce or a tragedy; or perhaps both”.

Surely Australians can demand, and legitimately expect, better than that.

Henry Ergas is a columnist with The Australian. Alex McDermott has worked in Australian public history for more than 20 years. He was recently senior history curator for the Democracy DNA exhibition at the Museum of Australian Democracy.

Late last month, NSW’s revised history curriculum for years 7 to 9 was released for comment. With a third of the population living in Australia’s oldest state, that curriculum is important in its own right; its likely impact on the teaching of history in other states only adds to its significance. But it is deeply flawed – and so is the process by which it is being finalised.