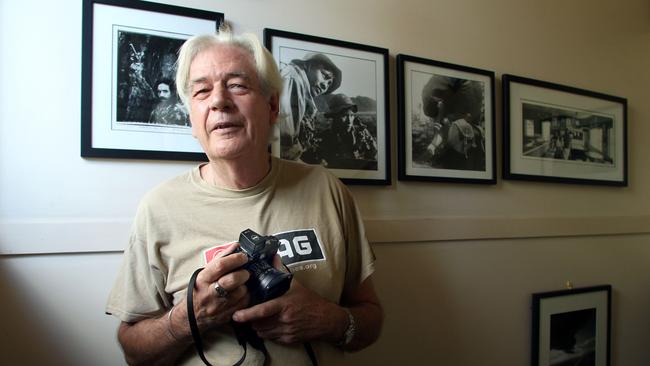

Tim Page captured the Vietnam War and the essence of its bedlam and madness

Photographer Tim Page was once asked to write a book that took ‘the glamour out of war’, but he didn’t think that was possible.

In Vietnam at the height of the war, Tim Page settled into a life of taking risks, drugs and photographs. When Apocalypse Now was released in 1979, few knew that filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola had based the manic Dennis Hopper character on Page. But to every photographer and journalist who passed through Saigon in those days, it was obvious.

Across the decades of incidents and accidents, people would describe Page as larger than life. He sometimes appeared larger than death too; when mortality knocked, as it did a few times, he brushed it aside.

Page died on Wednesday after battling cancer since May. He was 78 and had been living in Bellingen on the mid-north coast of NSW.

Some of his 750,000 images – from Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Cuba and more recently Afghanistan and East Timor – are on display at Washington’s Smithsonian National Museum of American History, the Tate Gallery in London and, permanently, in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon).

Page was included in Professional Photographer magazine’s list of the 100 most influential photographers of all time alongside such household names as Helmut Newton, Man Ray, David Bailey and Annie Leibovitz.

He was seriously injured in Vietnam on four occasions, notably in 1966 when aboard the American cutter Point Welcome in the demilitarised zone. It came under friendly fire from the US Air Force, then South Vietnamese gunners, and, not wanting to miss out, the North Vietnamese joined in. It was strafed with thousands of 50-calibre, armour-penetrating bullets. Its captain and another were killed.

In 1969, a soldier near him stepped on a mine and Page was blasted by shrapnel, one piece entering his skull. At a military hospital they declared him dead. Again.

In the 1970s, during a flourish of books looking back on the recently ended Vietnam War, a publisher suggested that Page – the conflict’s best-known photographer – write a book that would take “the glamour out of war”.

“Take the glamour out of war?” a perplexed Page said to a friend after. “I mean, how the bloody hell can you do that? It’s like trying to take the glamour out of sex, trying to take the glamour out of the Rolling Stones. I mean, you know that it can’t be done.”

The common ingredients of war don’t change: fear, horror and the dreadful noise. Page’s photographs captured all of that as boys whose lives weeks earlier were contained in orderly suburbs, found themselves in jungles being shot at and bombed while pointing their new rifles at an enemy they didn’t know and often couldn’t see.

Eddie Adams’ shocking 1968 photograph of a casual execution of a Vietcong captain on a city street may be the most remembered from that conflict, but more than others who charted those same events, Page’s images froze in time the often banal life of soldiering along with terror, bedlam and blood – sometimes his own – that would punctuate it.

His early years were unsettled. He worked for a time as a cook in Amsterdam and on occasion would take part in hash runs between Paris and there. Befriending an Australian, he set off on a whim in a Kombi van to drive overland to Australia. The van died and so did that plan.

He later drove with friends through the Middle East, across Pakistan, India, what was then Burma, and on to Laos. He always carried a camera and when there was an attempted coup in Vientiane, and with the country’s borders closed, he was the only westerner able to photograph events, filing his words and pictures and capturing the attention of the UPI news agency that offered him a job in Vietnam to record the war there which America had just joined.

Halfway through his five-year stint in Vietnam he took time off to photograph the Israel’s Six-Day War and then spent much of the rest of that year working in the US, which is how he came to be at the legendary Doors concert in New Haven, Connecticut, at which singer Jim Morrison was arrested on stage and bundled into a police van – along with Page.

He returned to Vietnam to roll the dice again, becoming friendly with photographers Sean Flynn – son of Errol – and Dana Stone, who on April 6, 1970, took off on motorcycles to see how the war was playing out in Cambodia.

They were never seen again, but Page, who returned to Vietnam dozens of times, spent years trying to discover their fate. He found out they had been kidnapped that day, handed to the Khmer Rouge, moved about the country and later murdered.

When I spoke to him earlier this year he was still following up clues and planning to return.

As the Vietnam War drew to a close, Jann Wenner, who had founded Rolling Stone magazine and hired gun-toting gonzo columnist Hunter S. Thompson, suggested the pugnacious Thompson join Page for a final tour there.

Thompson – whom Norman Mailer famously described as “a legend in successful self-abuse” – declined to go, saying Page was “far too dangerous”.

In England, when aged just 16, Page had a motorcycle accident and almost bled out. For a time doctors thought he had, and declared him dead. He wrote later: “I had died. I lived. I had seen the tunnel. It was black. It was nothing. There was no light at the end. No afterlife … A liberation happened at that intersection. Anything from here on would be free time, a gift from the gods.”

Tim Page, photographer, born May 25, 1944, Tunbridge Wells, Kent, England. Died age 78, August 24, Bellingen, NSW.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout