Thomas Midgley put lead in petrol before pumping CFCs into the sky

Thomas Midgley was a brilliant scientist, an out-of-the-box thinker whose inventions killed millions and almost ruined the planet.

Thomas Midgley is responsible for killing more people than anyone. He caused young men to become violent. He lowered the IQ of the world. He poisoned crops and caused millions of heart attacks and strokes.

This year marks a century since the American Chemical Society awarded Midgley its Nichols Medal for developing a compound that prevented the knocking in internal combustion engines. He called it Ethyl. The world called it lead, which had been known for millennia to be a deadly poison.

It wasn’t until August 1 last year, in Algeria, that the last litre of leaded fuel on Earth was pumped.

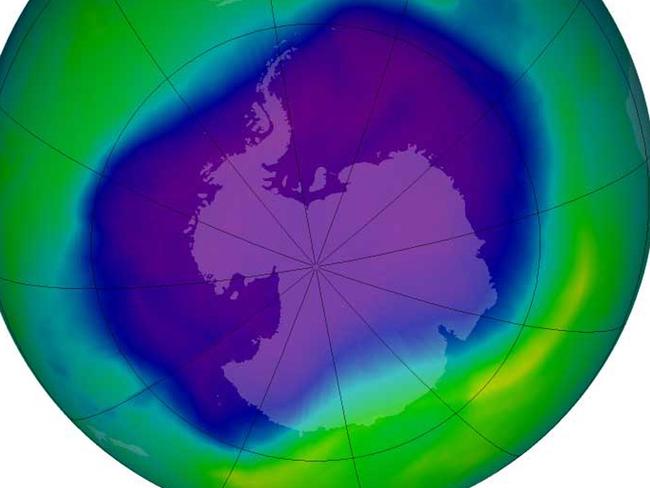

But Midgley wasn’t finished with the world. Later, he headed the team that created Freon gas as a refrigerant that, decades on, began punching holes in Earth’s ozone layer, raising UV levels that cause skin cancers, eye cataracts and disrupt ocean ecosystems. Its use was finally phased out in 2003 – 66 years after Midgley was awarded the Perkin Medal by the Society of Chemical Industry for this work.

This one-man environmental holocaust could not have known that chlorofluorocarbons would wreak havoc as they decayed in the upper atmosphere, but he was well aware how lethal lead could be. He suffered lead poisoning while developing Ethyl – and it almost killed him.

And when he did die, it was again because of the shortcomings in one of his inventions.

Midgley was born on May 18, 1889, in the small town of Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, but moved around in his younger years before settling in Columbus, Ohio, which he called home for the rest of his life. The family had inventor genes: his dad, also Thomas, invented several kinds of tyres made up of diagonally crossed rubber cords used on carriages and later cars; and his grandfather invented the inserted-tooth saw that allowed you to replace a saw’s teeth with another set while the first were sharpened.

At school, Midgley he was keen on sport and fascinated by chemistry. His teenage years coincided with what is known as the spitball era of baseball. Pitchers would spit on one side of the ball so that its trajectory changed as the air passed over it at a different speed, precisely the effect sought by the Australian cricket team when it was exposed by the Sandpapergate scandal in South Africa, in 2018.

Midgley was aware that native Americans had long used the bark of the slippery elm tree as a remedy for various ailments, including sore throats and wounds. Midgley combined it with water and it became a dark, sticky substance. Baseball pitchers took to his invention with enthusiasm, not least of which because it also made the ball harder to see as the light faded on game day.

In the late afternoon of August 16, 1920, at the Polo Grounds in Upper Manhattan, the New York Yankees were playing the Cleveland Indians and the Yankees’ Carl Mays pitched a spitball at batter Ray Chapman. Chapman can’t have seen it because it hit his forehead, breaking his skull. He started bleeding from the left ear, collapsed and was taken to hospital where he died the next day – major baseball’s only death. The spitball, in all its iterations, was banned.

By then Midgley had graduated from Cornell University with a degree in mechanical engineering but remained obsessed by chemistry and the periodic table, a copy of which he always kept in his pocket. He had already proved to be an original thinker, coming up with alternative solutions to the challenges of a rapidly expanding industrialised and motorised workplace.

He was recruited to the National Cash Register Company’s research department by legendary inventor Charles Kettering. Kettering had already come up with the electric cash register and was working on a system of confirming credit that would eventually lead to the credit card.

He became Midgley’s mentor – the young man called him Boss Kett – and when Kettering left to begin research into the many shortcomings of early cars, Midgley went with him. They became the research arm of General Motors.

By 1920, there were eight million cars on US roads, and 23 million Americans had driver’s licences. Cars would soon transform cities – workers no longer needed to live close to where they worked. Modern suburbs were born and so, too, mass manufacturing and assembly lines. The technology of making vehicles gave birth to appliances such as washing machines and stoves. The Twenties hadn’t started roaring but they soon would.

The biggest problem with cars at the time was what was called engine knocking, the result of the air and fuel mix in the cylinder prematurely igniting and causing uncontrolled combustion. It diminished the vehicle’s performance, damaged the cylinder walls, wasted fuel and was distractingly loud. The big carmakers of the era, especially Ford and General Motors, invested heavily into researching affordable solutions to the problem.

On December 9, 1921 – after testing all sorts of additives, including butter and camphor – Midgley discovered that adding one part of tetraethyl lead to 1000 parts of petrol eliminated knocking. However, he also quickly learnt that a build-up of lead corroded valves and spark plugs, so he added a newly found chemical called bromine. Advised by Kettering, who understood marketing, Midgley called this new fuel Ethyl, which sounded harmless.

More than 62,000 American girls would be given Ethyl as a name that year. Pierre Samuel du Pont, the president of General Motors, was fully aware of the perils of lead. In March 1922, as plans for moving to Ethyl Anti-Knock Compound were under way, he wrote to his younger brother, Irenee – a chemical engineer who would also have known – that the new petrol was: “A colourless liquid of sweet odour (that was the bromine, lead has no smell), very poisonous if absorbed through the skin, resulting in lead poisoning almost immediately.”

The first words of an inglorious chapter in capitalism had been written. Immediately, those working in Ethyl plants started to become ill with involuntary tremors, paralysis and hallucinations. Six died at one plant, 15 at another. In October 1922, a lab director at America’s Public Health Service, noting the illnesses and deaths in the pilot projects, described Ethyl as a “serious menace to public health”. The public nicknamed the new fuel “loony gas”.

To reassure everyone, Midgley held a press conference – he may have invented such events – and washed his hands in it. He also wrote to the US Surgeon-General to assure him that “the average street will probably be so free from lead that it will be impossible to detect it or its absorption”. He then took a long break in Florida – to recover from lead poisoning.

Clair Cameron Patterson was born eight months before – in Dayton, Ohio, where, coincidentally, at the corner of Sixth and Main streets, the first gallon of leaded petrol was pumped. He went on to study chemistry and worked on the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb. He had a special interest in geology and the manner in which the lead from decaying uranium could be used to pinpoint the age of rocks. Using these techniques, his California Institute of Technology team announced in 1956 that the Earth was 4.45 billion years old. Of course, it is 66 years older today but his calculation has been proved correct.

Patterson kept finding his research contaminated by lead from other sources and eventually built a hermetically sealed lab for his testing. He believed he knew what was causing the ubiquitous presence of lead and scoured the globe to prove it, taking samples from ocean depths, beach waves, deserts, ice-core samples from Greenland and the Antarctic, and he even probed Egypt’s mummies. There was already 1000 times more lead in the atmosphere than occurred naturally, and a 600 times greater concentration in humans than should have been.

He sought to alert the world to this peril, doing so at great cost, losing research grants and contracts and being ridiculed by the big businesses that relied on lead in paint, petrol and in canned foods. Eventually, in 1976, by which time there were 342 million vehicles in the world, governments started taking seriously the impact of lead in the atmosphere, which studies clearly linked to elevated rates of hearing loss, hypertension, learning difficulties and seizures. The rise of lead in the atmosphere also correlated with increased rates of violence among young men and decreased IQ. The Japanese were first to move to unleaded petrol as, slowly, the rest of the world caught up, progressively lowering lead levels and then banning it as Australia did on January 1, 2002.

Seven years after the launch of Ethyl, General Motors had brought the refrigerator manufacturer Frigidaire, and Midgley was asked to developed a nonflammable, non-toxic gas to improve on its early models. His team came up with something in just three days, calling it Freon. Midgley showed how harmless it was by inhaling Freon and blowing out candles.

That wouldn’t be the problem. The ozone layer had been discovered in 1913 but little was known about it, certainly not that it protected Earth from the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. Freon and related gases were widely used for refrigeration and also as propellants for aerosols and in industrial solvents.

It was not until the mid-1980s that a physicist, Jonathan Shanklin – when asked by a member of the public at an open day whether the supersonic Concorde’s exhaust might be damaging the ozone layer – that he decided to check the handwritten levels recorded from readings of three ozone spectrophotometers (well, two actually, the Argentinians had stolen one during the Falklands War in 1982).

Shanklin soon discovered that the ozone layer had steadily depleted since the 1970s and, in some parts, a third had been lost. It had been found in 1974 that chlorofluorocarbons rose up to 40km above Earth and upset ozone formation, but industry dismissed the dangers. Shanklin’s paper, in March 1985, was better received by a population more attuned to environmental threats, and by 1987 CFCs were banned around the world.

While it should repair itself by 2070, the damaged ozone layer has led to rises in skin cancers and cataracts and killed phytoplankton, the building block of the marine food chain that also generates, via photosynthesis, half our oxygen.

Of course, Midgley, who obviously understood the dangers of lead, was not to know the damage his Freon would be doing 50 years after the fact.

In 1940, there were localised epidemics of polio, one of them in Ohio, and Midgley became one of 9770 Americans to contract it that year, losing the use of his legs.

At the 1944 convention of the American Chemical Society convention – Midgley was now its president – he addressed scientists with a poem. It read, in part: “Many men my senior may remain when I am gone, I have no regrets to offer just because I’m passing on, let this epitaph be graven on my tomb in simple style, ‘This one did a lot of living in a mighty little while’.”

He died four weeks later, accidentally strangled in a hospital rope-and-pulley contraption he had made to raise and lower the top of his bed and to tip him sideways out of it. He was 55.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout