The weird truth about Easter: everyone rises

The Christian faith is booming in Africa, Asia and Latin America but still declining in the West, though there are plenty of green shoots, signs of new life.

Pope Francis is nearing the end of his papacy. The choice of his successor is profoundly important. Francis has appointed a lot of cardinals from impoverished parts of the developing world but, as the global split in Anglicanism shows, religious leaders in the developing world tend to be more religiously religious – that is, more conservative in belief and practice – than their counterparts in the West.

Evangelical Christians in the US, a goodly number at least, are seeking to break free of their extremely troubled attachments to Donald Trump. But who knows what Trump’s latest adventures mean for the culture?

The Christian faith is booming in Africa, Asia and Latin America but still declining in the West, though there are plenty of green shoots, signs of new life.

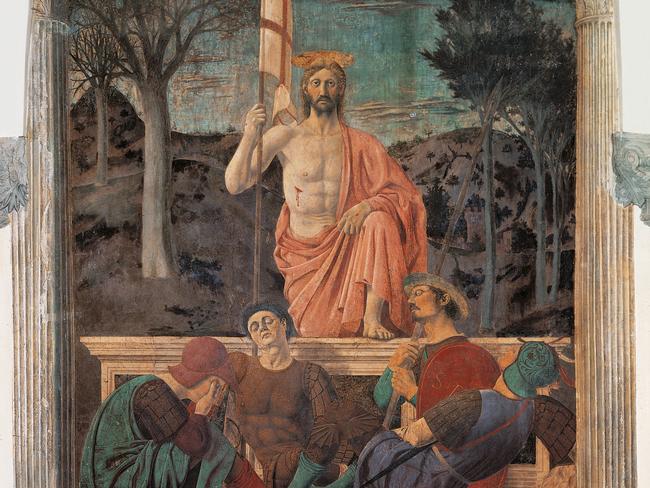

We should remember what Christians believe about Easter. They believe Jesus, the son of God, rose from the dead and lived among his disciples in his physical body. As Anglican Archbishop of Sydney Kanishka Raffel puts it in his Easter message: “Jesus’ resurrection was physical and real. Death really was defeated.”

But did you know that virtually all Christian denominations teach, as a matter of core belief, that all human beings will rise from the dead to live for eternity in their physical body? This isn’t a fringe belief but a central teaching.

The best chance for Christianity to grow again in the West is not to hide but to proclaim its radically weird teachings.

Western culture is now determinedly anti-Christian. You can no longer manage Christianity on a business-as-usual basis, balancing the books, administering well and expecting the culture to respect your institutions that teach transcendent truth.

There were good reasons to vote for or against Scott Morrison and Dominic Perrottet. But it seems their religious identities – one Pentecostal, one Catholic – counted against them electorally.

Nonetheless, the Christianity most likely to appeal to this hostile, jaded populous is weird, radical, hopeful, friendly and demanding. A slightly nicer but blander version of the secular culture can appeal briefly to those looking for Christianity to relax its call to moral heroism, but this approach generally won’t inspire the young or attract anyone for long.

Similarly, an exclusive emphasis on social justice activities without the supernatural will lead people to conclude they don’t need Christianity to pursue social justice, don’t need it at all.

The religious movements that grow today, especially among the young, typically have explicit supernatural beliefs, exist in a living community, embody solidarity with the poor or suffering, and offer their followers a sense of personal divine experience.

This is pretty much how early Christians lived.

Raffel tells Inquirer: “The extraordinary courage and missionary zeal of the early Christians, and the same courage and zeal of those Christians who live in the most difficult circumstances today, was not motivated by any universal sense of human morality. It was motivated by an encounter with the risen Jesus. The secular West has separated the morality from the majesty and inevitably distorted the morality.

“Any attempt to win over that society just by holding up a mirror to it and its moralising distortions is bound to fail.”

There’s strong sociological evidence most Christians in the West, even active believers who go to church, have very little idea of what their denominations formally believe.

Christianity is a supernatural religion, with vast spiritual and eternal claims. Everything about it is radical and a bit wild. Christianity is a faith that offers comfort and acceptance, but it’s also a faith of repentance, commitment, life change, prayer and forgiveness, and the unnatural practice of putting others first. It provides space for all the passionate heroism, meaning and destiny life can contrive. It’s bold, not bland.

Even many Christians who believe in eternal life may be vague about the physical resurrection.

But like all Christian beliefs, it’s there in plain sight, unmistakeable, in the New Testament.

Paul, in his first letter to the Christians of Corinth, writes: “”Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have died. For since death came through a human being, the resurrection of the dead has come through a human being; for as all die in Adam, so all will be made alive in Christ … The last enemy to be destroyed is death.”

Paul later uses the image of the seed. It can’t grow until it dies in the earth.

Christians believe that after death, before resurrection, the soul is in conscious communion with God. On the cross, Jesus promises the good thief: “Today you will be with me in paradise.” No Christian thinks Jesus a liar.

Paul, in his second letter to the Corinthians, describes this period for those who have died in the friendship of God, but before their bodily resurrection, as being “away from the body and at home with the Lord”. These are not isolated references in the New Testament. Nobody much beyond religiously devoted folks reads it these days, so its spiritual radicalism, its uncompromising, revolutionary vision about the destiny and the dignity of every human being, has slipped away from popular consciousness.

Christianity should shout this spiritual radicalism from the roof tops, if that’s what it really believes.

Roger Scruton, the great philosopher, in his sublime volume, The Soul of the World, argues religious movements are mistaken to minimise the spiritual: “The real question for religion in our time is not how to excise the sacred, but how to recover it.”

For centuries, Christians gave detailed, systematic thought to what the afterlife would be like.

Thomas Aquinas, the great systemic theologian, deduced that human bodies in paradise would not experience decay or suffering; would be luminously beautiful, not film star looks exactly but from each would shine the light of Christ; they would do whatever the soul commanded, and they would be able to move through solid forces, as the risen Jesus moved through walls.

The Christian teaching that all human beings will live forever in physical bodies has big implications for heaven.

It’s right to say heaven is essentially the friendship of God, but it will also be a place. It’s right to look forward to heaven. So where will heaven be?

It will be right here, but here will be transformed.

In his letter to Roman Christians, Paul writes: “For creation waits with eager longing … creation still retains the hope of being freed, like us, from its slavery to decay … creation will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God.”

This grants creation, and all human beings, profound worth and dignity.

In the earliest days of Christianity there was a false teaching, Gnosticism, which held, among other things, that the created universe was inherently evil and only the spirit was good. Early Christians vigorously, decisively rejected this hatred of the flesh.

Irenaeus, one of the most important early Christians, was taught by Polycarp, who was taught by John the Apostle. He famously declared: “The glory of God is man fully alive.”

By being fully alive, Irenaeus doesn’t mean being an Olympic athlete or a Rhodes scholar but being united with God in a purposeful life. Irenaeus defended the integrity of the human being, and of all creation, against the idea that only the spirit counts. (Last year Pope Francis elevated Irenaeus to the status of doctor of the church, meaning his teaching is most highly regarded.)

Today the situation is reversed. Christians must defend the integrity of the soul against those who think only the body, only the physical world we now inhabit, matter. The Christian vision unites body and soul. Both are essential, both honoured.

Let me offer a story of how this sometimes works out.

A little over a year ago my younger sister, Bernadette, aged 60, died of cancer, which she fought for seven years. It was a tough, tough battle.

We hadn’t been especially close in adult life. She was my sister and I loved her. She certainly loved me more than I deserved. But our lives took different directions, different interests, different friends, we lived in different cities. We never fell out but we weren’t especially close.

After she got sick we talked much more frequently on the phone. She was cheerful and kept her worst sadness away from our conversations, though she often talked of her cancer and the practical challenges it imposed.

She didn’t live only within the cancer though. When much of the cancerous bone of one leg was removed, she kept horseriding, kept working. She was a positive person but she’d had a life with its share of difficulties and disappointments.

A short unhappy marriage seemed to be followed by years of looking after everyone else. My father got sick and then died, my mother had years of sickness before she died, so too my older brother. It’s fair to say Bernie was the main person looking after them. Generally women still do much more caring, it seems to me, than men.

We thought her cancer was stable but suddenly it spread to her brain and in a minute she was in hospital. Our niece Siobhan, who looked after Bernie with great care and devotion, rang me unexpectedly to tell me the doctors had said it was virtually all over and Bernie had only days to live.

Amazingly, next day she rallied and doctors talked of treatment options. We didn’t know it, but this one good day was just a gift at the end of her life. I spoke to her by phone that night and she sounded great. I said to her in that conversation that she should be proud of her life, that she had led the Christ-life of service to others. She replied: “I don’t think I’m as brave as him.”

Next day she took a turn for the much worse and was gone in a couple of days.

There was one last thing to do for her. I asked my friend, Father Brendan Purcell, an Irishman and a great priest, who lived in the same city as Bernie, if he could see her, to bring the sacraments Catholics want at the end. She hadn’t been conscious much at all but she revived, miraculously, to speak to him lucidly for 15 minutes.

He wrote to me: “She was obviously pleased that a priest had come. We chatted about her Irish heritage. She said she was happy to receive the three sacraments: confession, anointing of the sick, and the Eucharist.

“My usual way of approaching a general confession is to list the Ten Commandments – including getting a laugh from her when I quoted the Dublin song: “You should never push your granny off a bus … because she’s your daddy’s mammy.” Of course I can’t say what her answer was to that. Then the anointing of her forehead and hands with oil consecrated on Holy Thursday, a participation in Jesus’ death and resurrection.

“Then the Eucharist, which she was able to receive. I had thought that mightn’t be possible. And after receiving Jesus, she spent a few minutes in deep prayer. After that, I asked her something about her life. She said she’d been looking back on her whole life. Her first realisation, she said, was thankfulness to all the people in the past, and now in hospital, who had shown her great kindness.”

As she was dying of cancer, her main feeling was gratitude. Bernie asked me, if I ever had the chance, to record how kind to her – wonderfully, wonderfully kind – the nurses at North Shore Private Hospital had been.

She barely regained consciousness and died the next day, or perhaps the day after. Siobhan was with her almost always and Bernie said just two things to her: “Hello, darling” and “What do you want me to tell your dad?”, our brother who died years ago.

Without breaking the seal of the confessional, Brendan assured me Bernie was headed “straight back to headquarters”.

Bernie had perhaps one last act of kindness. She loved Siobhan like a daughter and no one was kinder to her than Siobhan. Siobhan sat with her and talked to her by the hour. She went out at lunch time for 15 minutes. Bernie spared Siobhan the sight of her actual death, and so she died while Siobhan was out of the room.

At Bernie’s funeral, Brendan preached precisely on the theme of the physical resurrection and said: “Bernadette, sharing in the life of the risen Jesus, won’t only be reborn in her soul, in her spirit, but, like Jesus, she’ll rise again, not just her spirit but her body too. One day, your eyes will look into Bernadette’s eyes again, your hands will hold her hands in yours, you’ll hear her voice speaking with your own ears.”

The resurrection of the body is not theoretical. It’s weird, like many things that are deeply true, and it’s a central Christian belief.

At Easter it’s worth remembering, and celebrating.

This Easter it’s hard not to be a bit pessimistic – war in Ukraine, talk of war in Asia, endless other troubles. Christianity in the West is approaching two crisis points.