The unbearable lightness of being a company director

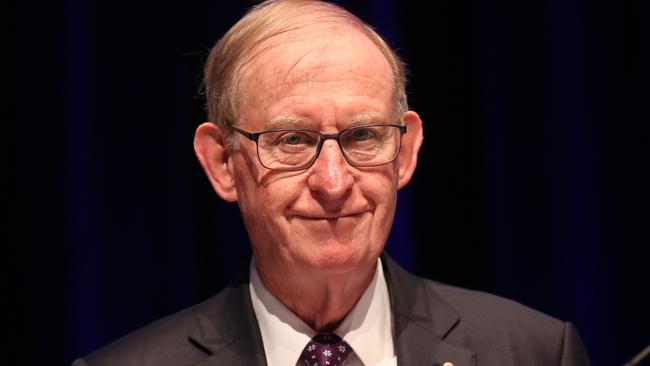

One of Australia’s most respected and successful business leaders has some advice for directors of listed companies. Get serious.

In an interview with Inquirer, Murray takes sharp aim at the Australian Institute of Company Directors, saying that it has lost its way.

“I don’t think the AICD has a serious interest in public listed companies anymore,” he says. “The bulk of their membership (87 per cent) is unlisted companies, private companies, public bodies and not-for-profits. Remember, they were involved in the group who wanted to put a social licence to operate into the ASX guidelines for public listed companies. That got knocked out.

“But here it comes again, in another guise, in the form of the AICD’s latest stakeholder guide for boards.”

Murray is scathing about the AICD’s latest political agenda released this month. “Elevating stakeholder voices to the board: A guide to effective governance” is a long-winded tome that, in sum, directs boards “to create a culture that puts stakeholders at the centre”.

It defines stakeholders as “non-shareholders”. Some of those stakeholders include parties who have contractual relationships with the company, such as employees and suppliers and customers. As Murray says, the law already protects their interests: they have priority in a liquidation.

But the AICD guide on stakeholders is so poorly, or deliberately, defined as to include anyone with the vaguest, and fleeting, interest in a company that it blurs the line between public and private interests in listed companies.

In doing so, Murray says, the AICD has abandoned directors of listed companies.

“To me, a company is owned by its shareholders whose shares are their own private property. They alone appoint directors who in turn owe their fiduciary duties to shareholders.

“If a director is precluded from fulfilling those fiduciary duties, they can’t act as a director. And that’s why I left AMP.

“I was being told by significant shareholders that they would requisition an extraordinary general meeting to get rid of me and one other director if I didn’t give in on an issue. Those industry fund shareholders were represented by their investment managers. I said to them ‘you are acting against your own interests here’.

“They didn’t change their position. So I left.”

Murray became a controversial figure in his time as chair of AMP when he stepped down in August 2020 after significant criticism by investors and others of the promotion of Boe Pahari following allegations of sexual harassment against him that had been investigated and settled with the complainant by AMP when chaired by Catherine Brenner some years earlier.

Murray’s critics might argue that he has a tin ear to emerging community views. He maintains that trying to second-guess changing community views is beyond the role of the company, and trying to satisfy activists driving the latest social agenda — be it #MeToo or any other social movement — will undermine a board trying to do its job, namely growing a business with new and better goods and services, creating more jobs, and producing profits for its ultimate owners — shareholders. Murray has never been a shrinking violet on important policy matters. And as the longest ever serving chief executive of Commonwealth Bank, founding chair of the Future Fund and chair of the Financial System Inquiry which reported in 2014, he has long been a giant of our financial and business community and his views carry serious weight.

“I haven’t met any good director who is disinterested in a company’s reputation because they know that a poor reputation in the community could reduce customer and employee confidence.

“That’s what companies deal with every day — it didn’t take this concept of ‘stakeholder theory’ to sort that out,” Murray tells Inquirer.

But when stakeholders include wider groups who fixate on social issues, it means “allowing people to try to impose on the company and its directors a liability that they don’t have”.

Murray says community expectations ought to be argued, debated, settled and reflected in law according to the established processes of a parliamentary democracy. “They should not be imagined and imposed on companies by interest groups going around the back door.”

The public interest is determined by the democratic process because it necessarily overrides some private interests in favour of the common good.

Boards, he says, have become unworkable “mini corporate parliaments” busily trying to second-guess community expectations. And the AICD is at the centre of a retrograde transformation of the listed company that undermines Australia’s economic prosperity.

If you turn companies into mini corporate parliaments, you need the processes of a parliament. The result is a modern listed company that is lumbering, bloated, bureaucratic and process-driven. By focusing their activity on their private contracts, there is a return to a clearer role and greater accountability which are at the heart of productivity improvement, he says.

Murray surely knows he is courting controversy again by uttering such sacrilegious ideas. In Australia, directors don’t speak up about the political makeover of the listed companies into vehicles for social justice.

But don’t take that deafening silence to mean consensus with the AICD’s obsession with politically correct campaigns that create governance nightmares for companies. Take the AICD’s May edition of its publication, Company Director. The title should read: “How to Screw Over the Company Director.”

In this latest edition, the AICD — with a new remit to “strengthen society” — has published an article telling its members not to sign “traditional non-disclosure agreements” when settling cases of harassment or bullying.

Rather, they should sign a “new form of NDA” which, according to this avant-garde thinking, would “not preclude the complainant from speaking about the complaint at any time in the future so they retain agency over how their story is told”.

This new style of Clayton’s NDA is perfect for hard-line activists but makes a mockery of contracts, contract law and what is in the interests of directors trying to do their job and the company’s owners. When company directors have to take a cold hard look at how to settle a bitterly contested dispute about personal behaviour, is it really in their interests to be told they have to sign such a one-sided, ideologically-driven settlement agreement?

So, whose interests are the AICD serving when they present this kind of misguided advice to their members?

Anyone who thinks there is not a culture war raging within corporate Australia needs their head read. But it is the most frustrating kind of culture war. You only hear from one side, those who are drilling political agendas deep into the daily operations of board rooms, those who fill board agendas with sessions on diversity and inclusion, how to make stakeholders feel special, quotas, pay gaps, corporate culture reviews and so on.

Whatever one thinks about each, or all, of these issues, there is little doubt that corporate Australia has become obsessed with fringe issues that excite and drive a small group of social activists. The other side is cowered into obedient silence by social pressures, threats of being expelled from the cosy directors’ club, and no more invitations to swanky dinners where heads nod in agreement with the high priests of political corporate culture.

The irony is that when companies don’t produce the goods — dividends and capital growth — investors scream blue murder. The financial media searches for scalps, heads roll, new board members are installed. And the same pattern repeats itself, with boards so busy addressing fringe issues dictated by woke corporate fashion that they can’t do their real work.

In corporate Australia there is no equivalent of JK Rowling or Lionel Shriver or Germaine Greer or Stephen Fry or Rowan Atkinson. Whereas these brave souls care about the inculcation of the deadening, regressive politics in their fields of expertise, corporate Australia is filled with cowards.

The result is an unbearable lightness of being a director in Australia. Sure, plenty of directors tell you privately what is happening to their company. Growth is stifled. Serious issues don’t get the attention they need because meetings are filled with a list of other more political issues that have nothing to do with growing a business.

Murray is the exception.

Asked when companies will return to their core role of driving economic prosperity, Murray says he thinks “it’s too far gone”.

“We will have to wait until there’s a general change in sentiment, some dissonance and then a consensus that things are not right,” he says. “That can come from great leaders. Unfortunately, it usually takes a serious threat, economic or otherwise. That’s when people start to realise those jobs in those companies are important, and the companies are important themselves. And then maybe you get an opportunity to reform things. But we haven’t had that for a long, long time.”

Australians ought to be grateful that Murray has returned to the public sphere. Directors don’t need to be protesting in the streets, he says, but they do need a new body with a laser-like focus on the difference between private and public interests and what is in best interests of the company.

Where this debate finally settles will have massive ramifications not just for directors, companies and capital, but for the country.

One of Australia’s most respected and successful business leaders has a few words of advice for directors of listed companies. Get serious. Get organised. And form a body that genuinely represents the interest of directors and listed companies. That, says David Murray, will best serve both them and the country’s future economic prosperity.