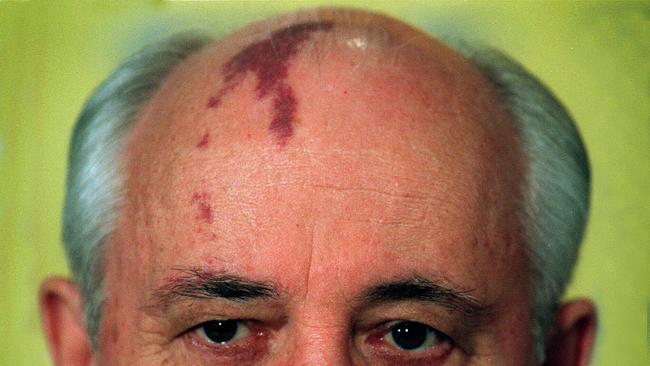

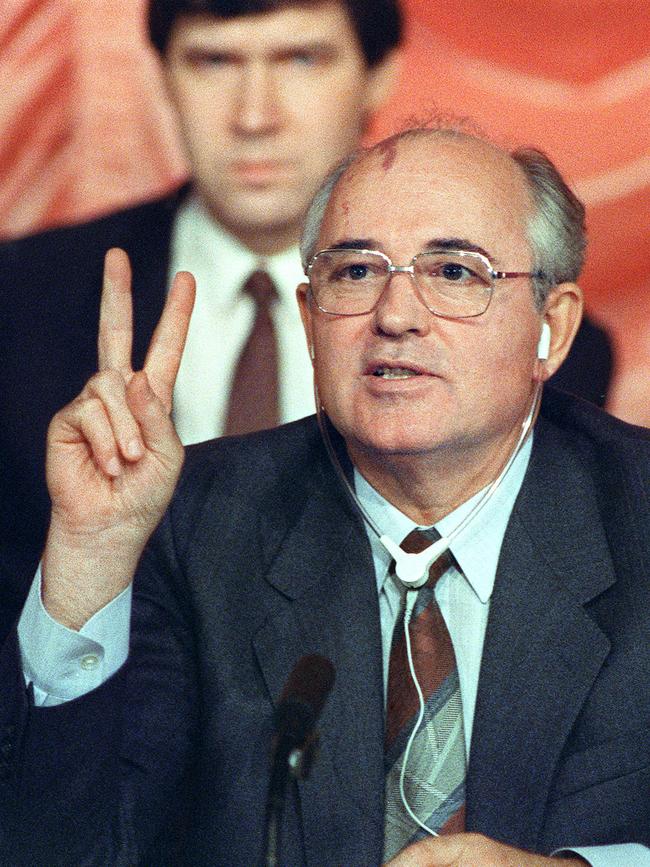

The tragedy of Gorbachev, USSR’s flawed reformer

The last Soviet leader risked all to reshape his nation but unleashed forces he couldn’t control.

The problem was not simply the biting cold of a Moscow winter, nor even the scorn that seemed to emanate from the busts of Marx, Engels and Lenin that looked down on the lecture hall in which I delivered my paeans to capitalism.

Rather, my discomfort arose from the chasm between the severity of the crisis gripping the Soviet Union and the capacity of its political system to manage dramatic change.

From 1985 to 1987 I had participated in a small study group which concluded that the collapse of the USSR, and of the Soviet empire, was highly likely, if not inevitable, and that its end would probably occur before the year 2000. By 1988-89, it was apparent that the difficulties were already coming to a head.

As oil prices plummeted, the Soviet economy teetered on the brink; separatist pressures, which had built up steadily during the Brezhnev era, threatened to tear the USSR apart; and where it was not simply paralysed by bureaucratic inertia, the machinery of government was in disarray.

The question was whether Mikhail Gorbachev, who had become general secretary of the Communist Party in March 1985, would be able to deal with the crisis. That he was full of goodwill was widely recognised; but far more than goodwill was needed to ride out the storm. And there were plenty of reasons to fear the worst.

To begin with, despite the adulation he was starting to receive in the West, it was scarcely clear that Gorbachev had a credible and coherent strategy. On the contrary, his highly publicised address to the 27th party congress in February 1986, which had been expected to set the parameters for a phased process of economic reform, seemed entirely detached from reality. Instead of taking the measure of the problems besetting the Soviet economy, it re-endorsed the then current five-year plan while announcing new growth targets that were literally incredible: from 1986 to 1990, agricultural output would double and national income would increase by more than 20 per cent.

To top it off, Soviet industrial production would exceed that of the US in less than two decades. It hardly needs to be said that the grandiose objectives had to be abandoned within weeks of their release. But they were never replaced by anything more sensible.

As Gorbachev faltered between more planning and much less, the Soviet economy ground to a halt, with only 11 per cent of the key consumer goods being in ready supply.

By late 1990, when the ill-fated 500 Days plan – which pledged, wildly implausibly, to remodel the Soviet economy in 500 days – died in the USSR’s increasingly tangled politics, Gorbachev’s close friend and adviser, Anatoly Chernyaev, could note in his diary that as far as the crucial economic issues were concerned, Gorbachev “is completely confused and does not know what is going on”.

To make things worse, the political headwinds were becoming ever stronger. The appallingly ham-fisted response of the state apparatus to the explosion at Chernobyl on April 26, 1986 had convinced Gorbachev that superficial change was not enough; but he greatly underestimated the hostility that would be provoked by a series of decisions that drastically shrank the role of the Communist Party, slashed the military establishment and purged the politburo.

Compounding the problems, precisely when the hostility started to boil over into outrage, he managed to transform Boris Yeltsin into an implacable foe, yet steadfastly refused to take up the many options he had for removing him from the scene.

Gorbachev, who had first promoted Yeltsin and propelled his ascendency, always viewed Yeltsin with contempt. That Yeltsin was deeply flawed is unquestionably true; he was, however, an extremely wily politician who knew how to seize opportunities and build coalitions, emerging, after his demotion from the Politburo in November 1987, as a formidable and absolutely unforgiving rival.

From then on, Gorbachev was forced to devote ever more of his time, and of his dwindling political capital, to retaining his grasp on power.

The result was a situation that soon became uncontrollable, as a cascade of crises – from a strike wave that threatened coal supplies, making national blackouts seem inevitable, to the outbreak of violent clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan – overwhelmed Gorbachev’s capacity to understand the factors at work and forge viable solutions.

In all those respects, Gorbachev failed, and did so virtually from the outset. But the errors were difficult, if not impossible, to avoid.

The suppression of debate – not just by repression but by a pervasive culture of conformity – ensured that the problems plaguing the USSR were rarely openly discussed and even more rarely seriously studied, meaning that reforms needed to be improvised as crises struck.

Within the state apparatus, there was no incentive, and even less ability, to change, as promotion almost always occurred on the basis of loyalty and seniority, deterring every form of criticism.

And in the absence of an independent civil society, there were no live forces that could be readily mobilised to replace the dead wood.

Nor could the approach which Deng Xiaoping was deploying in China be adapted to Soviet circumstances. The Soviet economy was far more centralised and top-heavy; and while the chaos of the Cultural Revolution had disrupted China’s communist elites and created space for reform, the Soviet nomenklatura remained as entrenched as ever.

It was therefore one thing to precipitate the tottering system’s collapse, as Gorbachev did, and quite another to design and put in place an alternative. Rather, it may be that the best that could be achieved was to clear the ground, so that, sooner or later, a better future could emerge.

That was certainly not what Gorbachev intended. Extraordinarily self-assured, he often compared himself to Lenin, whom he greatly admired and whose writings he knew extremely well. From Lenin he had acquired an unbounded faith in the power of leadership, along with the conviction that “when the locomotive of history comes to a sharp turn, only the steadfast cling to the train”; but he never thought – as Lenin did – that violence, like Achilles’ lance, could heal the wounds it had inflicted.

Rather, supremely confident that democratic socialism was genuinely feasible, he was convinced it should and would be achieved freely and peacefully, not only in the USSR but throughout the empire he had inherited. Increasingly isolated, he never wavered in his belief that it was possible to have “conviction without fanaticism, intelligence without discouragement, and hope without blindness”.

Lawrence Durrell opens his Alexandria Quartet with the beautiful line “in the midst of winter you feel the inventions of spring”. It was hard to feel that, all those years ago, looking out on Moscow’s snow and ice; it is, in many respects, even harder today. But Gorbachev did; for that, and for the courage to do what he could to steady an unsteady world, history will remember him.

Arriving at the Institute for the Study of Marxism-Leninism of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union during the tumult of the Gorbachev years, it was hard not to feel the “optimism of the will, pessimism of the intellect” that French writer Romain Rolland considered the hallmark of the intelligent person’s reaction to attempts to remake society.