The stars are our destination

Co-operation with a reinvigorated NASA will give the Australian space sector a huge boost.

Scott Morrison’s plan to pump $150m into Australian firms to develop technologies for NASA’s Mars ambitions is nicely timed to capitalise on a revitalised US space agency and a president keen to tap the pioneering spirit of the original astronauts.

Donald Trump’s interest in putting astronauts on the moon and Mars has boosted NASA after decades of tight budgets.

NASA’s success in landing humans on the moon in 1969 is one of humankind’s greatest achievements. Despite the accolades, public support for continuing moon missions quickly evaporated. Within a year, NASA’s budget was cut from $US5bn to $US3.7bn and was just over $US3bn by 1974.

Now the moon is back in vogue as part of NASA’s staged plan to visit and colonise Mars, with Trump and Vice-President Mike Pence pressing for a 2024 moon visit.

The moon has a fresh role 50 years after Neil Armstrong first set foot on it. It will be a test ground for travelling to Mars — a laboratory where astronauts practise living together for long periods, growing food, attending to their own medical conditions and ensuring sufficient supplies of water, hydrogen rocket fuel and oxygen.

Australian Space Agency chairman Rod Drury says Australian firms with an interest in space will now formally have a client — NASA — for the first time.

Australia’s mining sector could contribute to Trump’s space push, not because we’ll be digging up the moon and Mars anytime soon but because of the robotics the sector has developed for remote operation, says Drury, who was on his way to the US on Monday when he spoke to The Australian.

Australia’s experience at offering remote medicine in Antarctica is another. Australians could talk astronauts through medical procedures, give treatment advice and explain how to improvise with available equipment.

Robotics and miniaturisation, artificial intelligence, research and development in areas such as geology, education and 3D printing are other Australian strengths.

“This is a tremendous step forward for Australia’s growing space industry and will provide a significant injection of funding which will underpin both jobs and growth in our space sector,” Drury says.

“Strong leadership and support from the federal government has accelerated this growth in the domestic space industry. A partnership with NASA will provide the next big incremental step needed to ensure continued expansion in the industry.”

CSIRO’s astronomy and space science deputy director, Sarah Pearce, also sees Australia’s mining, robotics and autonomous operations as the key sectors.

She emphasises the importance of taking ideas developed for space and making them useful on Earth. CSIRO has been working on batteries and solar panels for use in space, Pearce says.

Australian universities also are keenly involved in space research. The Australian National University Institute for Space has been adapting ANU research. Scientist Francis Bennet says the institute has been working on optical communications that can transmit vast amounts of data to Earth from instruments in space.

Associate professors Matthew Cleary and Ben Thornber of the University of Sydney’s school of aerospace, mechanical and mechatronic engineering have been researching a more efficient fuelling system for rockets and satellites. Instead of rockets carrying oxygen and hydrogen fuel, they could collect oxygen from the atmosphere during their ascent, making entry into space easier and cheaper.

“Our advancement of modelling of high-speed propulsion is directly aligned to Australia’s strategic investment in a space agency,” Cleary says.

Travelling to Mars got a kick along in 2017 when SpaceX chief executive Elon Musk unveiled rocket designs to carry crews there by 2024. That would be preceded by missions in 2022 seeking water.

However, others see the timeframe suggested by Musk and US authorities as totally unrealistic. Kenneth Bowersox, NASA’s acting associate administrator for human exploration and operations, told a US congressional subcommittee last week that the space agency is doing its best to meet the White House-imposed deadline.

But he noted: “I wouldn’t bet my oldest child’s upcoming birthday present or anything like that.” Bowersox, a former space shuttle and space station commander, said it was good for NASA to have “that aggressive goal”. Many things needed to come together, such as funding and technical challenges, he said, for 2024 to stand a chance.

NASA has named the program Artemis after Apollo’s twin sister in Greek mythology and promises the first moonwalking team will include a woman. The pair would land on the lunar south pole, where vast reserves of frozen water could be tapped.

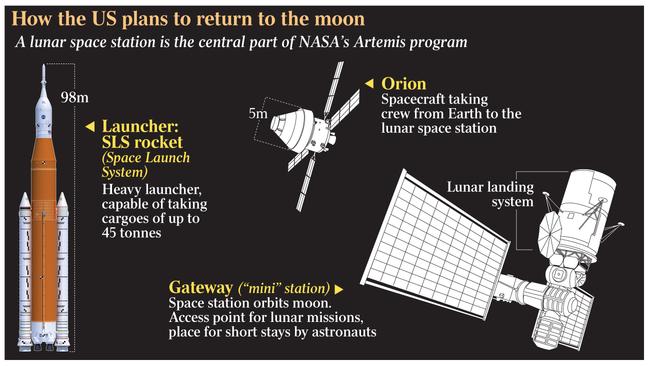

NASA’s replacement for the Apollo-era Saturn V rocket — the Space Launch System — is still in development. Its launch debut has slipped repeatedly and, according to Bowersox, will now occur no earlier than the end of next year. This initial test flight will send an Orion capsule around the moon with no one on board.

As for whether private companies such as SpaceX might beat NASA to the moon, Bowersox said: “I’d still bet on us — but they might be part of our program.”

The needs of astronauts on Mars will be different to the moon. Long-term survival on Mars will depend on self-sufficiency. Industries that offer self-sufficiency in space will be on fertile ground. Using energy from the sun to split water into hydrogen and oxygen for rocket fuel is one option.

Renewables will be a major source of energy in space but, if the past is any guide, nuclear energy will be used too. Already more than 25 small nuclear reactors have been used to keep electronics warm and working in deep space missions. The Mars Curiosity Rover has used decaying plutonium dioxide for seven years. The new Mars 2020 Rover likewise includes nuclear power.

NASA is developing the Lunar Gateway for the moon, a spaceship that will act as a temporary home and office for astronauts. It will support human and robotic missions on the surface.

On its website NASA says astronauts will visit the Gateway once a year, staying up to three months at a time while they conduct experiments, take trips to the lunar surface and practise living away from Earth for long periods.

Gateway itself will spark new industries. NASA says discussions are taking place with international partners to provide expanded living space, advanced robotics, transportation and science capabilities.

The rekindled interest in the moon and Mars by the US government is a welcomed change for NASA but the ongoing supply of government funding is a tough ask politically because it’s such a long-term project. Let’s hope those promoting travel to the moon and Mars are in it for the long haul.

Additional reporting: Agencies