The Solomons strategy

Sino relations are on the rise after the Pacific Islands nation dumped Taiwan.

For China, the rat is a sign of wealth and surplus and, as Sogavare noted, an aggressive attitude and entrepreneurial spirit. He was optimistic the new year would bring good fortune “as we work on developing our strategic partnership and interaction between our two countries”.

The Solomons were named by Spanish explorer Alvaro de Mendana in 1568 after the biblical King Solomon in the mistaken belief they contained great riches. But China’s interest in the region is based more on power than gold. Sino relations are on an upswing after the Pacific Islands nation dumped a 36-year diplomatic relationship with Taiwan in September last year in favour of the People’s Republic of China. The switch is a diplomatic coup for China, which is preparing to open an embassy on the Solomons’ main island, Guadalcanal.

Already there is controversy about what China’s intentions for the Solomons may be. There has been a failed attempt to lease an entire island with the potential for a deepwater port.

Promises have been made for a new hospital, court house, sporting stadium and other infrastructure. China is offering billions of dollars in infrastructure spending and the possibility of multi-billion-dollar loans.

By any measure, Solomon Islands is a vulnerable nation still recovering from a long period of civil unrest. Alarm has been sounded about the potential for debt-trap diplomacy in which funds are lent that cannot be repaid.

Australia, the Solomons’ biggest donor, has been increasing its engagement with the Pacific in response to China’s outreach. But it has focused its effort on building institutional strength rather than the Taiwanese model of giving each politician $1m a year for unchecked discretionary spending in their electorate.

Long-time China watchers in the Solomons say the issue is less complex when viewed from the mainland. “To China, the GDP of this country is nothing,” one long-time resident says. “One private (Chinese) company could buy this country overnight.”

He says the major reason for Chinese interest in the Solomons is military and strategic. The view from Honiara, scene of the most epic battles between Japan and the US during World War II, is that China is seeking to break the second chain of US containment of China. The first chain is The Philippines, Taiwan, South Korea and Singapore. The second ring, farther from the Chinese mainland, is Australia, Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea, Guam and Hawaii.

To achieve its objectives China is working with a troubled society and a corrupt political system. According to the Asian Development Bank, about 85 per cent of the Solomons population of 627,000 lives in widely dispersed villages of a few hundred people each. The economy is based on primary commodities; economic growth prospects rely on mining, agriculture and fishing, with some potential for tourism. The country ranks poorly in terms of global corruption at 77 out of 180 nations.

-

This series is supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism & Ideas

MORE FROM THE DIASPORA PROJECT: Overseas Chinese have mixed feelings about Hong Kong’s fate under Beijing’s rule | A tale of two Chinas | Winning over the locals is difficult business

-

Analysis by Denghua Zhang and Derek Gwali Futaiasi published by the Lowy Institute says politics in the Solomons is marked by instability, clientism, corruption, the challenge of urbanisation and a lack of development in rural areas.

Many of these issues combined to give rise to the civil conflict that took place from 1998 to 2003, sparking the Australia-led Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands to restore order.

The conflict started as ethnic tension between militants on Guadalcanal and settlers from nearby Malaita island. Chinese residents were targeted for violence during the unrest, which has left a raft of social problems compounded by a big rise in the percentage of young people in the population, poor education and chronic unemployment.

Andrew Leung, a resort and restaurant owner, remembers the heyday of Honiara in the mid-1980s when there were was an active social scene with five country clubs, tennis, basketball, golf and waterskiing.

“In the old Chinatown there was a basketball court and you would put 20c in the slot to bring the lights on and people would all come out and play basketball together,” says Leung, whose father moved to Solomon Islands from Hong Kong in 1962 as an engineer.

“It was a cosmopolitan and multi-racial community with people from all over the world. Now is it mainly just Australians.”

Leung still has photographs of the five-star restaurant — with plush furnishings imported from mainland China — that he developed, only to see it burn down in the uprising.

Trouble started in the late 1990s and from 2000 to 2003, Leung says, there was complete lawlessness until RAMSI’s arrival. “In 2006, when they burned Chinatown down, that was the end of it,” Leung says. “It went from bad to worse and then worse to worse.”

Leung has rebuilt and says he wants to stay out of politics.

“I am not for China or for Taiwan,” he says. “We don’t see ourselves as Chinese, we are neutral. But in China they see me as a foreigner. Here, the locals see me as Chinese, and in Australia they see me as Asian.”

Leung says the troubles in Honiara were between locals rather than attacks against the Chinese. “The violence to Chinese was just looting,” he says.

Hotel owner and controversial political figure Sir Tommy Chan remembers being forced to defend his property during the uprising.

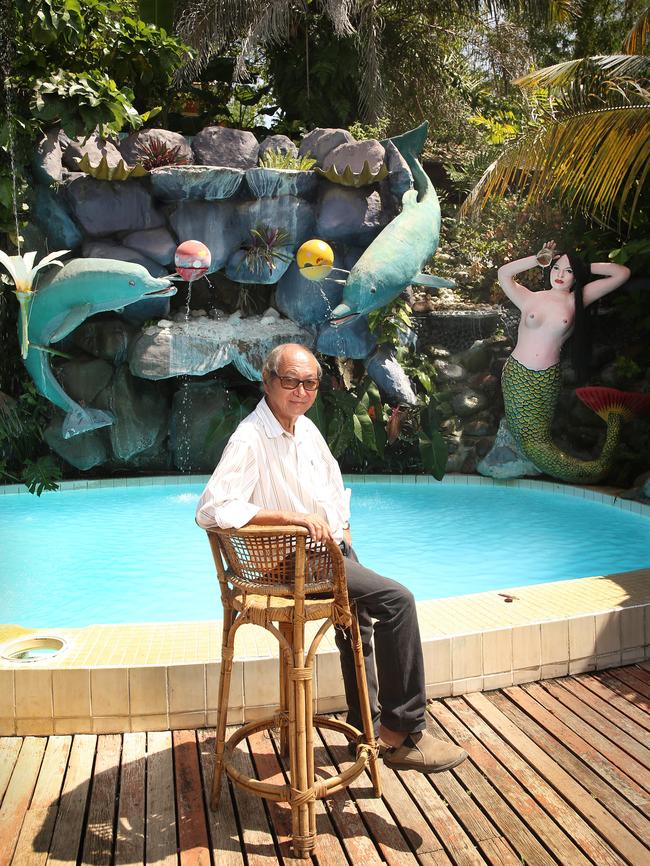

“I used to run three public bars and was the Solomon Island Bruce Lee,” he says. “When Chinatown had riots in 2006 the Australian RAMSI people said: ‘Tommy don’t go down there, it is not safe.’ I said: ‘Shut up, I have to go save my shop.’ ” Chan still runs the Honiara Hotel, an eclectic hilltop compound with concrete statues of mermaids and horses around the swimming pool. Unlike Leung, he had a higher profile in Solomon Island politics, which he now says he regrets as a waste of time.

Chan says he steers clear of the diplomatic tensions between China and Taiwan.

“For me, Taiwan used to help us,” he says. “China fighting with Taiwan — it is their business and nothing to do with us. We are under the Commonwealth, the Queen is our boss. We are friend to all and enemy to none.”

But if China is to become more involved he wants it to build something rather than take. “One thing I want them to do is free education. Because of the tensions, one generation has no education. Children are dying trying to raise money for school fees. Another child hanged himself because his parents could not afford to buy a uniform.”

Wendy Ho is a board member of elite Chun Wah School, which has strong links to the Solomon Chinese community and has a Chinese teacher sponsored by the mainland; it also has had teachers arranged through Taiwan.

“The school tried to reintroduce the Chinese language about five or six years ago but the standard is still not good enough because the Chinese teachers turn over too fast,” Ho says. “Some of the teachers don’t want to stay too long.” Poor medical facilities and lack of security make it hard for Chinese-run businesses to attract workers from the homeland. Some employers, and even the school, have started recruiting from The Philippines.

“If you are a young Chinese parent you will always think about what is best for the kids,” Ho says. “For younger parents that come here now, the mentality is to say ‘My child is not learning enough.’

“The view is they finish the school day early and just play, they are not learning much. In China you have to go to learn piano, learn chess and a lot of other skills and extras from three years of age.”

As in PNG, Chinese traders dominate retail across the Solomons. There are tensions and conflicts between locals and shop owners, and concerns about the trading practices of some retailers.

Tax and duty avoidance are considered to be big problems by a new generation of Chinese who see the Solomons market as an opportunity to “hit and run”.

“They smuggle goods in, under value them or do not declare,” one local businessman says. “In the past it was not serious and not that big scale, but now they have containers full of goods and they declare it all as toilet paper.”

With closer monitoring from Australia and New Zealand there have been notable seizures, with goods confiscated and burned.

Ho says while there may seem to be a lot of new buildings and Chinese-run wholesale businesses, many do not survive. “The ones that are really doing well are the ones that have been here a long time,” she says. “The ones who have just come in, you have to be smarter to survive.”

In terms of diplomatic relations, Ho says she thinks most of the Chinese community in Honiara would prefer China to Taiwan because of the consular services.

“They probably do feel better at the thought of a Chinese embassy here,” she says.

During the 2006 riots, when Chinese shops were looted, some residents approached the Taiwan embassy for help but were rejected.

They tried the China embassy in PNG and the mainland sent planes to evacuate them.

With billions of debt funding on offer, the influx of Chinese to Solomons is probably only beginning.

To celebrate Chinese New Year, Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare took a full-page advertisement in Guadalcanal’s Island Sun newspaper to offer Beijing his warmest wishes for the Year of the Rat.