The race around the world for an effective coronavirus vaccine

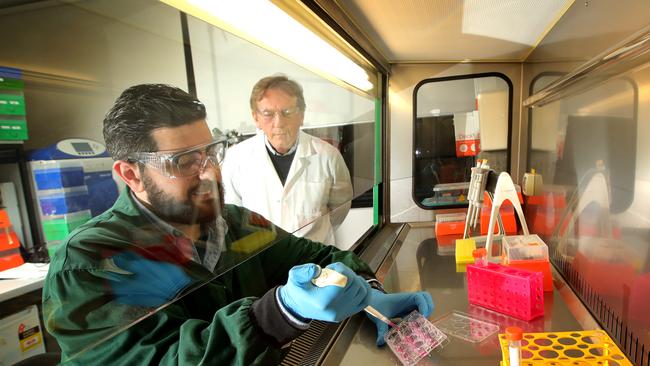

The global quest by scientists for a coronavirus vaccine is about to become very real for scores of Australians.

The global quest by scientists for a coronavirus vaccine is about to become very real for scores of Australian volunteers. The US biopharma Novavax has chosen an Australian company, Nucleus Network, to run its first phase of clinical trials into its COVID-19 vaccine candidate.

Hundreds of Australians have stepped forward to be injected with the Novavax product, with 131 to be involved in the phase one trial.

They’re not alone. Volunteers across the world are stepping forward to participate in almost a dozen clinical trials of vaccine candidates being conducted. At the same time, thousands of healthcare workers in countries around the globe are taking drugs in the name of medical research, hopeful they may play a small part in minimising sickness in those who catch COVID-19.

People are giving plasma, too. In Red Cross blood banks throughout Australia, hundreds of people who have recovered from coronavirus are donating the “liquid gold” that will be injected directly into the bodies of people in hospital with COVID-19.

As restrictions ease, chief health officers and politicians are stressing that Australia’s case numbers may rise. They dread a second wave. All eyes are on the hope of a vaccine; until then, trials of therapeutics ranging from US President Donald Trump’s purported “miracle drug” hydroxychloroquine to repurposed HIV therapies to anti-inflammatory antibody products are all doctors can use to try to fight the COVID-19 scourge.

Eleven vaccine candidates are being tested in clinical trials around the world.

The University of Queensland is leading the race in Australia, with its candidate, dubbed the S-clamp, to move to human trials in July after encouraging results in animal studies.

UQ’s quest has been funded by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, which is also helping to finance the development of 11 other COVID-19 vaccine candidates globally. CEPI had been funding the work of UQ scientists — who have developed a special molecular clamp that stabilises a vaccine’s protein — before the pandemic hit. The molecular clamp was developed to be used in a pandemic that was previously only being planned for.

Like the UQ and Novavax vaccines, several other recombinant protein vaccine candidates are being developed to target the coronavirus’s spike proteins that protrude from SARS-CoV-2 particles. These include several candidates in China, which is the most advanced country in COVID-19 vaccine development.

As well as traditional protein-based vaccines, there are also other technology platforms being used. Four of the candidates being trialled use “viral vector” technology. This method protects against pathogens by using animal or human viruses as a “vector” to infect a host with DNA-encoded antigens that kickstart an immune response.

The method has limitations — antibodies may be produced against the vector, not the virus. There could also be challenges for large-scale manufacturing.

Viral vector vaccine candidates are being trialled by three Chinese companies and another at Oxford University in Britain. Oxford’s candidate is being tested on ferrets by the CSIRO.

Another four candidates in development use a nucleic acid platform, where the vaccine packages up an encoded version of the virus in genetic material and is directly injected into the host. This gives instructions to the host to create antigens, which are foreign proteins from the virus, sparking an immune response.

Nucleic acid-based vaccines are quick to produce and cost-effective but need careful cold storage to be distributed. No DNA or messenger-RNA vaccine has yet been licensed for use.

Despite the lack of track record, these DNA and mRNA-based vaccines are a new frontier in vaccine science, says the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance’s director Kristine Macartney.

“The world has been gearing up to deliver vaccines in smarter, faster and more innovative ways,” Macartney says. “There have been experiences that have led us to understand how important it is and how possible it is to move rapidly in response to a massive global pandemic of this nature.

“The SARS experience told the global community how quickly a virus can travel around the world. That, as well as major influenza vaccine seasons, have driven a lot of vaccine innovation and that’s been enabled by all sorts of incredible scientific advances in the last decade.”

US biopharma Moderna is at the forefront of the mRNA vaccine race. Moderna released results of preliminary human trials this week that showed its vaccine candidate was safe and stimulated an effective immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in a small number of human volunteers.

Another two vaccine candidates are being trialled by Chinese companies using “inactivated virus” technology. This is where the virus is killed or weakened so it is not pathogenic but its structure remains intact to spark an immune response. There are many existing vaccines that use this method, but manufacturing is difficult to scale up.

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations is funding 12 vaccines in development, including the UQ candidate, Novavax and Moderna’s product. At CEPI’s last count, there were about 130 vaccine candidates in development throughout the world.

Garvan Institute immunologist Stuart Tangye is hopeful that of all the COVID-19 vaccine candidates, at least one will turn out to be successful. The signs are good, he believes.

“In individuals who have had mild infection, the responses seem pretty normal: these people generate immune responses,” he says.

“You can detect neutralising antibodies in the blood from these individuals. And that’s promising because that’s essentially the biomarkers which people rely on to gauge the success of a vaccine.”

As the heady race for a vaccine continues, doctors on the frontline are turning to novel therapeutics. More than 200 potential COVID-19 therapeutics are being tested in more than 1100 clinical trials around the world.

Two of those randomised clinical control trials in Australia are testing the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine, the drug that Trump is taking as a preventative against COVID-19.

Hydroxychloroquine, an antimalarial drug, has been used in the treatment of the auto-immune diseases rheumatoid arthritis and lupus for the past 50 years. They’ve been shown in test-tube studies to inhibit the replication of SARS-CoV-2, and scientists believe their best use may be as a prophylaxis.

So far, there has been no conclusive evidence of hydroxychloroquine’s effectiveness as a treatment in COVID-19. But that only proves the need for gold-standard randomised clinical control trials, Australian scientists say.

More than 70 hospitals throughout Australia are signed up to a clinical trial testing whether hydroxychloroquine can prevent the onset of severe disease. In addition, a trial involving more than 2000 healthcare workers will test whether hydroxychloroquine is effective as a preventative.

Ian Wicks, a rheumatologist at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and lead investigator in a clinical trial being run by the Melbourne-based Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, says hydroxychloroquine is a “remarkable drug”, despite being potentially dangerous for those with heart rhythm problems.

The drug’s mechanism of action is not fully understood. But its efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 is likely to be as a preventive measure, before the virus has taken hold.

“In rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, it seems to reset the immune system towards better immunoregulation,” Wicks says. “I guess we’d be quietly confident that this trial will provide a definitive answer to the question of whether this drug is effective as a preventative against coronavirus, or at least to inform further evaluation.”

Another clinical trial under way in Australia is being run by the global biotechnology company CSL Behring which, in conjunction with Red Cross Lifeblood, is collecting plasma from patients who have recovered from COVID-19.

Some of the convalescent plasma Lifeblood is collecting is being infused directly into COVID-19 patients in hospitals in Australia. And CSL is using the plasma to manufacture a product called COVID-19 Immunoglobulin — a concentrate of the antibodies created by the body to fight COVID-19.

The HIV drug Remdesivir has also been the focus of attention. It’s not being tested on COVID-19 patients in Australia because of limited supplies, but clinical trials in the US and China are under way, so far with mixed results.

Other therapeutics being tested include monoclonal antibody treatments, and non-specific immune enhancement therapies such as interferons.

All of these trials require human volunteers. Scientists have had little trouble so far attracting them, a fact emblematic of the intense desire, not only by scientists but by ordinary people, to crush COVID-19. As the first Australians are soon injected with a vaccine candidate in Melbourne, the world waits for a cure.

“I am hopeful,” Tangye says. “We can see the success that vaccines have had, obviously on infectious diseases, but also on society, the community, the economy. They are a mainstay of modern medicine.

“I’m optimistic we’ll get a vaccine. The timeframe, though, is what’s really unclear.”

ADDITIONAL REPORTING: ANGELICA SNOWDEN

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout