The prosecution of Tony Maddox was textbook ... but it was also mean

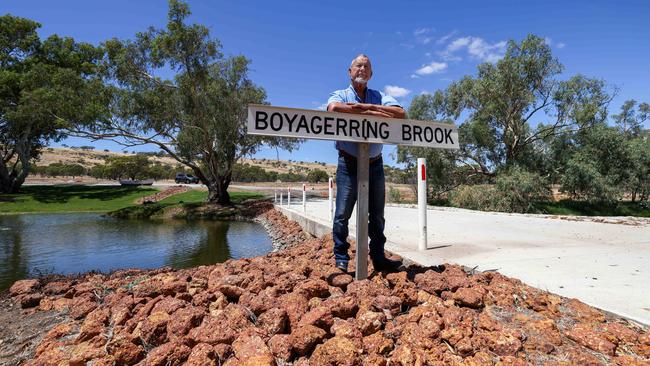

Farmer Tony Maddox concreted the top of a culvert through a creek at his farm northeast of Perth. He then spent two years and $100,000 defending himself.

The prosecution of Tony Maddox for damaging Aboriginal cultural heritage was textbook but it was also mean. Maddox concreted the top of a culvert through a creek at his farm northeast of Perth, then spent two years and $100,000 defending himself.

The 72-year-old’s conviction in the Perth Magistrate’s Court in February only bolstered claims made during the voice debate that Australia’s deference to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture had gone too far.

Maddox is convinced an Indigenous advisory body in the Constitution would have divided Australians but says the preservation of Aboriginal culture does not have to.

“I don’t want to bulldoze Aboriginal heritage … we do need laws for that. I am not one of these people who thinks it should be open slather, go for it, no consequences,” he says.

“But I think it should be called the Australian heritage act. That way everyone can get behind it.”

Maddox’s idea is for one set of laws with varying levels of protection for Australia’s ancient Aboriginal story, the colonial story and post-settlement story.

In and around Maddox’s farm about an hour’s drive northeast of Perth, that might mean careful development on the Avon River and its tributaries out of respect for the Noongar creation story about the giant Wagyl snake that made waterways.

Maddox has time to read and think since a cancer diagnosis in 2024. He is nostalgic about the lost places of his childhood in Perth’s leafy western suburbs, including a hot pool on the Swan River at Dalkeith and World War II bomb shelters that became his cubbies.

“My heritage has been demolished by white people,” he says. “I know what it’s like to lose heritage, I am with Aboriginal people on that. Their heritage should be protected.”

The former electrician, real estate agent, business owner and occasional auctioneer has combed parliamentary debates, pored over regulations and got to know Noongar people in his home town of Toodyay for the first time.

“I had some good talks with the Noongar people in my town,” he says. “I told one bloke: ‘It’s like the government has written an act for you, against me. It’s wrong.’ ”

Farther south in Mandurah, the descendants of settler families are collaborating with Aboriginal elders against their council’s plan to build a pub on the city’s prettiest park. Initially, non-Aboriginal residents fought the pub alone by arguing that local landowner Victor Adam gave Hall Park to the people in 1951 to be kept as public open space and never sold to developers.

Then in 2025 locals learned the Noongar community had its own objections; Hall Park had earlier been the camp of Noongar leader George Winjan, reported to have survived the Pinjarra massacre of 1834. Winjan lived on site as a guest of the Sutton farming family. He was respected as a mediator between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people.

“We’ve certainly learnt a lot in the past couple of months,” local Brad Mitchell says. “This has brought us all a bit closer together for a damn good cause.”

Noongar elder Ivy Bennell was speaking for all opponents of the pub when she told Mandurah council in February that Hall Park was precious: “It’s free, it’s attractive, it’s fun-loving, it’s memory-making, it’s our way of life in our Mandurah community.”

Nothing surprises Maddox now, not even Mandurah council cheerfully planning a pub at Winjan’s camp while he gets dragged to court for upgrading an existing road on his own property.

Ironically, Maddox says, what he did was exempt and perfectly legal under the heritage fix that WA Labor briefly ushered into law in 2023. He says farmers are worse off since a ferocious backlash forced the Cook government to repeal those laws.

Finding lasting agreement on what Aboriginal cultural heritage is and how to protect it has eluded successive governments for two decades in Western Australia.

The evaporation of political agreement on Aboriginal heritage reforms in the first weeks of the Cook Labor government is a warning for all governments. There are reviews of Indigenous cultural heritage laws under way in the Northern Territory and most states. Federally, Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek continues working towards a rewrite of the contentious Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984.

Under those laws – which the Coalition also has pledged to reform – a small Aboriginal charity from Bathurst, NSW, convinced Plibersek that blue-banded bee dreaming at the site of a proposed goldmine near Blayney warranted her intervention. Miner Regis Resources says Plibersek has killed the goldmine. It is fighting her in court. Plibersek’s decision went against the advice of the Orange Local Aboriginal Land Council, whose elders said the blue-banded bee dreaming was not real.

Plibersek preferred the testimony of what the Orange land council considers an illegitimate group. Under NSW law since 1983, it is the Orange land council’s role – and the role of the state’s other 120 land councils – to speak on Aboriginal culture and heritage in their respective areas.

However, the Orange land council should not have been shocked. The Bathurst group, called the Wiradyuri Traditional Owners Central West Aboriginal Corporation, had been on the rise.

In May 2021, federal Coalition environment minister Sussan Ley blocked the Mount Panorama-Wahluu go-kart track at the request of the Bathurst group – its first win under the federal Aboriginal heritage laws that both sides of politics want to change.

This success helped build credibility for the Bathurst group that it has relied on since in dealings with local, state and federal authorities.

It now seeks to register an Aboriginal place at the top of Mount Panorama, home to Australia’s most famous car race, because the ashes of elder Brian Grant were recently scattered there. The matter is unresolved and with the NSW government.

The challenge of getting Aboriginal heritage right – and avoiding revolt – was laid out at 91 workshops held across WA in 2022 and 2023. By then, WA Labor’s reforms had passed both houses of state parliament. However, farmers and Aboriginal people made demands that were irreconcilable during workshops to settle the accompanying regulations.

Many pastoralists said they must be fully exempt from any Aboriginal heritage legislation. That was a call for immunity from prosecution including on stations with rock art and other ancient artefacts.

Many Aboriginal people said they must get a veto. In short, they wanted the ability to approve or block mines and other projects. WA Labor would not entertain it.

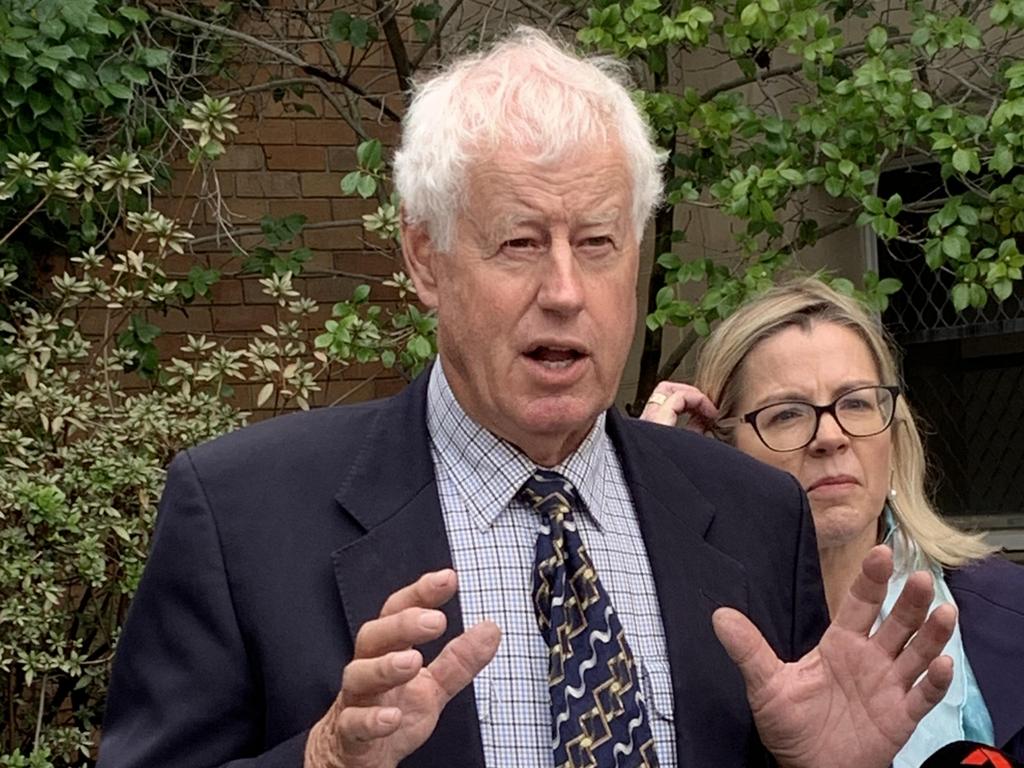

Former WA Labor treasurer and Indigenous affairs minister Ben Wyatt says there had been earlier broad consensus on Aboriginal heritage reforms between the Aboriginal community, farmers, pastoralists and other land users such as miners, local government and prospectors.

The state’s first Aboriginal heritage laws had bipartisan support in 1972 because West Australians were appalled by the pilfering of ancient stone installations from Wongai ceremonial grounds on Weebo station in the goldfields. But 50 years later, the 1972 laws needed an overhaul.

Wyatt’s rewrite was well advanced in 2020 when Rio Tinto legally blasted the Juukan Gorge rock shelters where thousands of artefacts and tools revealed Aboriginal occupation dating back 47,000 years. The miner had permission under the 1972 laws. Meanwhile – according to the state’s top heritage bureaucrat, Ben Harvey – the same laws required a small landholder to get a permit to cut dead grass.

“I knew I had to remove the day-to-day activities of land users from a complex approval process,” Wyatt tells The Australian. “The low-level activities of farmers, local governments, pastoralists, prospectors needed to be exempt from a legislated approval process.

“And the Aboriginal community, particularly recognised native title holders, got the statutory right to be part of the WA land use regime around significant Aboriginal sites that were going to be impacted by activity.

“It would mean that land users who were going to have a significant impact on land needed to come to an agreement with native title holders, a process that takes place today, but would ensure standards around those agreements were consistent. Importantly, the new regime increased the penalties for deliberate destruction of significant Aboriginal sites and gave the government the capacity to regulate fees and timetables of approvals. For four years representatives of all these groups worked very well together and agreed upon what became the new Aboriginal heritage regime. While it was not perfect, the new regime received the broad support from the main land users and all the WA political parties.”

Pastoralists and Graziers Association state president Tony Seabrook is adamant he was never part of a consensus on WA Labor’s heritage fix but Wyatt says the PGA and its members were “engaged participants in the long process to agree a new regime up until the politics of the voice referendum took over”.

Wyatt had retired from parliament when WA Labor introduced and then swiftly binned the new heritage regime in August 2023, a few weeks out from the voice referendum. The laws were characterised by voice opponents as a taste of worse to come if an Indigenous advisory body were enshrined in the Constitution.

“In the end, the WA Farmers and PGA campaigned against the new regime as it was a convenient position to take to undermine support for the voice referendum,” Wyatt says. “Similarly, some Aboriginal organisations, in particular representative bodies, decided they wanted more from the new regime and also opposed the new heritage regime. I am still unclear as to the motivations of these organisations.

“And when you lose political consensus on reform of such contention, then you lose the reform.

“Roger Cook was absolutely right to repeal the new regime, for when he looked out over the political landscape he found no support, including from those who should have known better and gotten behind the legislation, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal.”

In Toodyay, Yued Noongar man Robert Miles says there is an uneasy feeling in the community since Maddox’s conviction under the old Aboriginal heritage laws that are again the law of the land in WA. Aboriginal people feel blamed for Maddox’s ordeal.

In a letter to his local newspaper, The Toodyay Herald, Miles writes: “It’s important to remember that in this case, it was a non-Aboriginal neighbour who reported the breach. Yet Noongar people have unfairly taken the brunt – and continue to be targeted. This ongoing scrutiny is draining and deeply frustrating.”

Miles says Maddox is “a gentle person” who was let down badly when voice opponents succeeded in bringing back the state’s old heritage laws from 1972.

About 600 farmers rallied against WA Labor’s fix for Aboriginal heritage laws in confronting scenes at Parliament House in West Perth. Miles said the farmers did not appear to know those laws introduced a long list of exemptions for them to go about their work unencumbered.

“WA farmer ‘peak bodies’ failed in their responsibility to educate their members about the existing (and the revoked) heritage laws,” Miles writes. “Instead of ensuring compliance, they allowed misinformation to spread unchecked, fuelling division and shifting blame. It is not Aboriginal people’s role to educate landowners on longstanding government laws.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout