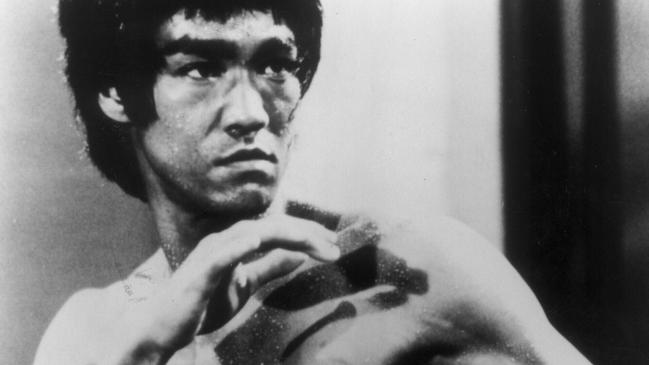

The poet-philosopher who made himself famous using his fists

The legendary actor and martial arts star – whose breakthrough film, Enter the Dragon, came out 50 years ago – saw himself as a poet-philosopher.

“Be water.”

To many, this gnomic statement summons the grace, power and inner strength needed to defeat a great foe. Four-time NBA champion Klay Thompson has cited it as on-court inspiration for superhuman feats. In Hong Kong and Catalonia, pro-democracy demonstrators adopted it as a slogan for massive protests as they played cat-and-mouse games in the streets with authorities.

It is also the perfect epigram for Bruce Lee, the actor and martial artist who popularised the Taoist aphorism and remains a global cultural icon 50 years after the release of his crowning achievement, Enter the Dragon, in August 1973.

Lee remains hard to categorise. A street fighter in his youth, he disdained using martial arts as sport, though many Mixed Martial Arts fighters name him as their inspiration. During a period of bitter protests over race, prison uprisings and the Vietnam War, Lee paid little attention to politics. Nonetheless, he stands today as a global hero of the underdog, a screen on to which millions have projected their yearnings.

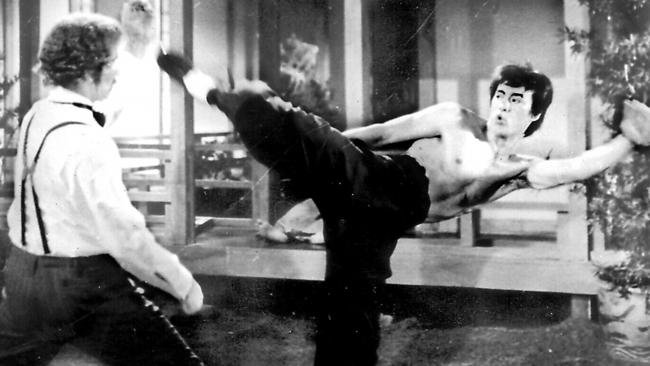

In his brief life, Lee sought to modernise Asian fighting arts and spread the philosophical ideas undergirding them through the most unlikely of forms – American action film. His reputation rests on the four martial arts movies he completed in the early 1970s before his shocking death at 32, weeks before the release of Enter the Dragon, due to severe cerebral oedema.

Three of those movies were made in Hong Kong, where Lee had gone – some might say, retreated – after being rejected by Hollywood as “too Chinese” for the TV series Kung Fu. That series starred David Carradine in yellowface with fight scenes that were a poor imitation of the arts on which Lee had worked so hard. Yet his fame has long eclipsed even the most popular of his action movie star friends, such as Steve McQueen and James Coburn, whom he served as a personal trainer during his struggling years.

Lee’s breakthrough with Enter The Dragon seems more relevant than ever before.

Lee was born in 1940 in San Francisco to a Cantonese opera legend, Li Hoi Chuen, and wife Grace Lee Oi-Yu, who were raising funds in the US for the war against Japan. The Li family returned to Hong Kong, where they experienced the Japanese invasion and then the flight of refugees after China’s civil war ended.

Lee became a minor celebrity as a child actor. As a teenager he became adept at wing chun, a gung fu style promoted by a Cantonese refugee named Ip Man, and tested his skills as a street fighter. Despite his comfortable upbringing, he was an enthusiastic participant in the beimo subculture; illegal fight clubs where contestants bloodied each other on rooftops or secret locations.

Because he had drawn the attention of the police, his parents sent him back to the US, where he was a citizen, at the age of 18. In Seattle, he became a martial arts teacher and fought racism in a personal way when he and his wife, Linda Emery, married, defying the objections of her family.

In 1964, Lee was invited to a karate tournament in Long Beach, California, organised by a native Hawaiian kenpo master named Ed Parker. His appearance – where he demonstrated his “one-inch punch” – caused a stir. His style divided the martial arts community but also secured him an audition for a TV show playing Charlie Chan’s “number one son”.

Thankfully, the remake was never made. Instead, Lee won a role as Kato, the black-masked chauffeur for The Green Hornet, a television remake of the popular radio serial.

For the first several episodes Lee was given almost no lines. But, eventually, his stunning physicality began to be felt on the show, then noticed. Soon Kato dolls were selling as briskly as Green Hornets. The show was cancelled after just one season, during which Lee was never paid more than a stuntman’s wages.

For the next several years he pivoted between being a gung fu master to the stars and attempting to break through Hollywood’s bamboo ceiling.

Five years later, almost on the edge of poverty, he left for Hong Kong. There he achieved breakaway success with films The Big Boss, Fists of Fury and The Way of the Dragon.

But Lee was not satisfied to simply out-punch, out-kick and out-leap his opponents. He also wanted to be regarded as a poet-philosopher. He had taken philosophy classes at the University of Washington, read widely and wrote poetry.

He was especially drawn to the writings of Zen Buddhism popularisers such as Alan Watts and Daisetz Suzuki, and to the Chinese Taoist classics. He pressured the producers and the studio to include these ideas in Enter The Dragon, which gave the action film an unexpected gravitas.

At a time when it was rare to see a Chinese-American actor in a major film, Enter The Dragon opened up new ways for Asians to be seen. No longer inscrutable, evil and alien, Lee was David in a world of Goliaths, securing justice with his bare hands and sometimes nunchakus.

Today statues of him can be found on the Hong Kong waterfront, in Chinatown in Los Angeles, and in Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina – where it stands as a monument to ethnic peace – and even Kogarah in Sydney. His ideas live on in the Warrior TV series, which is based on his original treatment for what became the Kung Fu show, and directly addresses the history of anti-Asian violence and racism with rip-roaring fight scenes.

Lee lifted his “Be water” quote from the Taoist classic, Liezi. It appeared first in a TV show he did in 1971 called Longstreet, written into the script at his urging by his gung fu student, Stirling Silliphant. The full quote, which Lee analysed in college almost a decade before, remains an expansive and evocative piece of poetic wisdom:

If nothing within you stays rigid

Outward things will disclose themselves.

Moving, be like water.

Still, be like a mirror.

Respond like an echo.

It is one measure of the tragedy of death that Bruce Lee never had the chance to expound on the last two lines for the millions who would come to follow him. But 50 years later, his imperishable screen image still finds its way to us, shimmering just out of reach.

The WALL STREET JOURNAL

Jeff Chang is the author of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation and the forthcoming Water Mirror Echo: Bruce Lee and the Making of Asian America.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout