The potential lone wolves hiding in plain sight on our streets

Angry individuals of the so-called pro-Palestinian protest movement are ripe for radicalisation. They have been given free rein to conduct their increasingly threatening and illegal behaviour on our streets for nearly two years. It has to stop.

On Friday morning AEDT, an FBI spokesman told a press conference that Jabbar acted alone. CCTV footage that originally was thought to show accomplices placing two improvised explosive devices close to Bourbon Street now is thought to show Jabbar before the attack, when he drove a rented Ford pickup truck into a crowd of people celebrating New Year’s. He reportedly had a remote detonation device. It is unclear whether he was killed before he could detonate the IEDs or if the trigger mechanism failed.

Whatever the reason, the failure of the IEDs to detonate saved many lives. It may be that his intention was to force people to flee Bourbon Street, moving to the side streets where the IEDs were placed. That points to a style of terrorist attack we saw in Paris in November 2015 and Brussels in March 2016 where, in both cases, several detonations occurred, or were planned, to maximise casualties from people fleeing the initial attacks.

Less clear is Jabbar’s radicalisation process. He claimed to have joined the Islamic State group, but does that mean he had contacted the group through social media or simply that he intellectually adopted its ideology? The answer to that is important for considering future threats and Islamic State’s intentions in Western democracies.

Jabbar posted several statements on social media before the attack saying he had converted to Islam before the northern summer in 2024. That might link to a reported 10-day trip he made to Egypt that year. An Egypt visit certainly will be of deep interest to investigators. Was Jabbar seeking to contact Islamist extremists – a high-risk endeavour in Egypt? A colleague refers to the current regime in Cairo as running the “jail on the Nile”.

Media reporting has emphasised that Jabbar was born and reared in Texas. There is little commentary about his wider family background – seemingly a deliberate blackout on their origins – but much information about his three marriages, military service, business failures leading to financial difficulties and a modest police record which, while noteworthy looking back, hardly indicates a disposition to terrorist ideology.

There is likewise a good deal of uncertainty in media reporting on Jabbar’s religious background. I have seen reports saying he was raised as a Christian. Perhaps there is a Coptic Orthodox background. Other reporting of family members and from an imam, Fahmee Al-Uqdah, based in Beaumont, Texas where Jabbar’s father lived, described him as “scholarly, quiet” and as an “extraordinary human”.

Jabbar then took an unexpected turn in behaviour in 2024, “being all crazy, cutting his hair” after converting to Islam, according to an individual married to an ex-wife of the attacker. It’s pointless speculating until more detail emerges.

Jabbar appeared not to be on any FBI or security warning list. Nor does it seem that the FBI now considers there was a link between the New Orleans attack and the explosion of a Tesla Cybertruck outside the Trump International Hotel in Las Vegas hours later.

Both vehicles were hired from peer-to-peer car-sharing company Turo. That’s a striking coincidence but it may be just a coincidence. Turo reports it had more than 360,000 vehicles listed for hiring in the US in March 2024. (What are the odds that two such vehicles would be used on the same day to commission two unrelated terrorist acts?)

The driver of the Tesla in Las Vegas is now known to be Master Sergeant Matthew Alan Livelsberger, a soldier with the US Army 10th Special Forces Group. He shot himself before detonating a vehicle full of high-powered fireworks and fuel canisters. At this stage there is no clear sense of Livelsberger’s motivations.

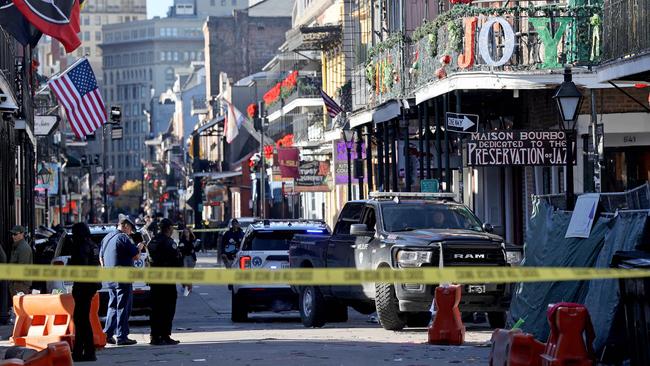

In New Orleans, it appears that a 2019 report by a New York security firm concluded that Bourbon Street was at risk of a “vehicular ramming” attack. Barriers at either end of Bourbon Street, which is used as a pedestrian walkway, did not appear to properly function.

The attack happened when the barriers – not bollards, it seems, but a ramp-style barrier that can be lifted to prevent vehicle access – had been removed for repair ahead of the Sugar Bowl university football playoff quarterfinal held on Friday morning AEDT in New Orleans.

I spent time walking through the French Quarter in 2007. Bourbon Street, like most in the vicinity, is quite narrow, lined by two-storey buildings, many of which have wrought-iron railed verandas on the second level. It is a beautiful area abutting the Mississippi River and miraculously escaped Hurricane Katrina in August 2005.

Bourbon Street is the centre of a thriving party district and in 2007 I thought it was a prime target for a mass casualty terrorist attack.

This is no claim to prescience – given my background my first thought in any area is how might someone attack that location. Bourbon Street at any time of day has thousands of tourists on the street and hundreds on the overlooking balconies.

Clearly Jabbar put some planning into his target. He drove from Texas to New Orleans, a five-hour trip on Interstate Highway 10. He could have chosen many other potential targets.

Had the full scope of the plan been realised – detonating two IEDs remotely, exploding the bomb in his vehicle and using his rifle after the vehicle stopped – many more people could have been killed. Jabbar’s military training would have assisted him, but note that he was an IT specialist, not a combat soldier.

The planning that went into this attack inclines me to think he was helped by minds more attuned to thinking about terrorism.

There is a long way to go in official investigations, which hopefully will provide answers to questions about the long and short-term causes of these two incidents.

Beyond those answers more thinking is needed about how we respond to such attacks. Here are my thoughts, which can only be preliminary, about the lessons we should draw from the New Orleans and Las Vegas attacks.

Beware investigation by press conference

It seems there is no American official alive who does not aspire to be the star performer at a press conference. Yet we all know that today’s “certainty” – such as Jabbar’s “three accomplices” – can be overturned on an instant.

Of course, the same is true for my own and others’ commentary. It’s a useful reminder to treat any early reporting about an incident, terrorist or otherwise, with extreme caution.

It’s equally striking that patterns of behaviour emerge: no “lone wolf” is ever truly alone. There are family ties, online connections, travel, a detailed back-story. Invariably they show a person operating in a network and a milieu of ideas that shapes their behaviour.

‘Zero to 100’ violence

Well before the Covid pandemic, security professionals were worried about the speed to violence that could turn, for example, an unhappy flyer or person in a shop queue into an angry assailant.

Latent anger is on the rise, with serious implications for security in crowded public spaces.

Whatever sparks that anger also may spur radicalisation as individuals look for a way to channel that emotion.

We see this not only in the US but also increasingly in Australia.

Rapid speed of radicalisation

Like business collapses, radicalisation to extremist violence seems to happen first slowly, then very quickly. Jabbar’s exemplary military service, his struggles to get business ideas off the ground, his quiet demeanour – these things apparently marked his first 41 years of life. Perhaps only the past six months brought out a jump to radicalisation.

This explains the difficulty faced by police and security services. A person can be “known to authorities” as a fixated individual, for example, without any indication that behaviour may leap into terrorism. What triggers that final rapid move to violence?

Australia’s terrorism threat advisory system has a five-point scale. We are at level 3, probable. Level 4 is expected and level 5 is certain. The problem with these last two categories is that we may have only hours to respond to that trigger point. That’s barely enough time to mount a pre-emptive response, let alone condition public expectations.

Attraction of Islamist extremism remains high

Islamist extremism wasn’t defeated when Islamic State was crushed in Mosul in 2017. The West just lost focus. Islamic State and other groups remain a powerful ideological force. They offer a certainty, now and in the eternal life, which some people – many in fact – will kill for.

This is not just in the Middle East. For some in Muslim diaspora communities in the West, and handfuls of non-Muslim individuals who may be willing to adopt an extremist Islamism, this ideology is a powerful force.

Western attempts to deradicalise feeder groups have failed, as have most attempts in Muslim countries. (Indonesia may be an important exception to that statement.)

A ‘spark’ needs tinder

Something sparks individuals to radicalise to the point of being willing to commit violence. As Australians know, a spark needs tinder.

A source of tinder for Islamist extremism in Australia and many Western countries today is the so-called pro-Palestinian protest movement, which for more than a year has been active on our streets, growing, pushing the boundaries of threatening and illegal behaviour, recruiting and training people, and mixing Islamist and green-Marxist “progressive” groups.

My view is that the Albanese government has underestimated the risk presented by this protest movement. This has happened because, in the Left of the Labor Party, there is deep sympathy for the anti-Israel and, in some cases, anti-Semitic roots of progressivism. Our universities have been teaching this ideology for decades, equipping many on the left of politics with an ideology they take into political activism.

Australian Jews have borne the brunt of the protest movement’s attacks. To our collective shame, the rest of the country passively watched that development. There has been too much willingness to excuse the protesters as people simply letting off steam or exercising democratic rights.

This is a high-risk strategy. Beware the spark if you let the tinder accumulate.

We can’t lose focus on counter-terrorism

ASIO was right to lift our counter-terrorism alert level to probable in August 2024, after lowering the threat level to possible in November 2022.

The more I look at the national threat levels, the more confusing they seem. When the threat level is lowered or raised, what does that mean for the money, staff effort and political focus devoted to counter-terrorism?

After the 9/11 attacks in the US in 2001, Australia’s police and intelligence services swung towards boosting counter-terrorism. Budgets were increased but not so much that the agencies had to reduce their rate of effort on counter-espionage. After about 2015, the priority swung back to countering a huge increase in Chinese covert influencing and espionage. It is fair to say that counter-terrorism took the brunt of internal “efficiencies” needed to refocus. Today, our security agencies face the highly difficult task of dealing with “all the threats, all the time”.

It’s clear that we cannot take the priority off counter-terrorism.

I struggle with the view that the best approach is to adopt the catch-all term of “politically motivated violence” rather than, to use ASIO boss Mike Burgess’s phrase, stress “a twisted view of a particular religion”. To be clear, the threat is not Quakerism. It’s Islamist extremism.

Bollards are back

My strong suspicion is that there will be many local councils, businesses and others in Australia that will have put crowd safety measures on the backburner after the ostensible defeat of Islamic State and the withdrawal of Australian forces from the Middle East last decade.

Those decisions to put dollars to other uses should be reviewed in light of the Bourbon Street attack, where 14 lives were lost for the want of working barricades.

Like Londoners today, those of us attending crowded events need to get used to, and become part of, a community system that is aware of potential threats and has some idea about how to respond.

Where is Albanese?

As at 4pm, Friday afternoon, there was nothing on the Prime Minister’s web page about the New Orleans and Las Vegas attacks.

In a four-line statement posted on X, Anthony Albanese said on Thursday that he was shocked by the New Orleans attack and offered “first thoughts in this moment” to the victims.

“First thoughts” are nice, but Albanese continues to be the spectator at his own parade. He is “appalled” at what happened. One might think that would spur the Prime Minister to action. But no. There is no grit, no plan, no direction, no energy and not the least sense of what he might do to prevent or respond to such an appalling attack should it happen here.

All Australians are appalled by the attack in New Orleans, a shocking act of violence aimed at people celebrating the new year together.

— Anthony Albanese (@AlboMP) January 1, 2025

Our first thoughts in this moment are with the victims and their loved ones. Our nation stands with the people of the United States.

Peter Jennings is director of Strategic Analysis Australia. He was executive director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute from 2012 to 2022 and is a former deputy secretary for strategy in the Defence Department (2009-12).

Investigations into the terror attack on Bourbon Street in the French Quarter of New Orleans continue to move fast, with the emerging picture about the assailant, Shamsud-Din Jabbar, becoming more complex.