The long and winding road of a 22-year-old suffragist

Vida Goldstein’s political passion was sparked by the battle for Australian women’s right to vote.

By the early 1890s, the movement for Australia to become a federation of colonies, collectively governing in their own right, was well under way. The idea of becoming a unified nation had been on the cards since at least 1880, and the ensuing years had been devoted to wrangling about such matters as defence, foreign policy, immigration, trade and transport.

Also discussed was whether Australian women should be given the vote, and there were differing views from the outset. For the first time in Australia’s colonial history, the men who had set up and ruled every public office and institution were having to consider whether to let women in. Men who asserted that women’s responsibilities began and ended with the home and children were being petitioned to give up some of their power.

It wasn’t as if giving Australian women the vote was an outlandish request: there were precedents, both in the US and closer to home. New Zealand had granted voting rights to its women in 1893, the first sovereign nation to do so, though it stopped short of allowing women to stand for parliament. The suffrage movement was well under way in Victoria by late in the decade.

Indeed, Victoria looked at one point as if it would become the first Australian colony to allow its women the franchise. In 1891, James Munro, a conservative known as the “temperance premier” because of his dislike of alcohol and its influence on the community, welcomed a deputation of women’s temperance groups: they wanted to convince him that giving Victoria’s women the vote would help in the fight against excessive alcohol, one of the greatest dangers to the welfare of women and children.

Unfortunately — and in a pattern that was to become depressingly familiar — the conservatives in his government refused. Not discouraged, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union combined with Victorian and Australian suffrage societies put together what became known as the “monster petition” to allow women the vote. The largest petition ever presented to Victoria’s parliament, was a strong and stirring affirmation of belief:

That Government of the People, by the People and for the People, should mean all the People, and not one half. That Taxation and Representation should go together without regard to the sex of the taxed. That all Adult Persons should have a voice in Making the laws which they are required to obey. That in short, Women should vote on Equal Terms with Men. Your Petitioners, therefore, humbly pray your Honourable House to pass a Measure for conferring the Parliamentary Franchise upon women, regarding this as a right which they most humbly desire.

Dozens of women armed with pencil and paper took to the streets, roads and lanes throughout the colony, in city and country, knocking on the doors of people from all walks of life and getting as many signatures from women as possible.

Vida Goldstein, aged 22 and a member of the Victorian Women’s Suffrage Society rank and file, took to the campaign with enthusiasm. She discovered that it was one thing to sit outside a bookshop asking passing women to give a shilling for a hospital building fund and quite another to actively seek expressions of agreement to a proposition many found confronting.

In her pamphlet The Struggle for Woman Suffrage in Victoria, written many years later, Goldstein described the experience. The canvassers, she said, had to be ready to deal with a range of anti-suffrage arguments and declarations, from “I don’t think we need it” to “I’ll ask my husband what he thinks”. The petitioners were rejected by women “whose interests ended at the garden gate’’ but welcomed by those who did charitable or philanthropic work.

It was good to see, said Goldstein, that the wives of working men supported the cause, as did their husbands. Indeed, she believed that the feeling of equality between men and women was most vital in the industrial suburbs. Never once were the canvassers met by a working man who said: “I won’t allow my wife to sign the petition.” On the contrary, if the husband opened the door he would call his wife, saying: “There’s a lady who wants to know if you want the vote.” Invariably she did. But in the more favoured suburbs, a husband would quite frequently refuse to allow his wife to sign, or a wife would say meekly and wistfully: “I’d like to sign but my husband won’t let me.”

Still, Goldstein thought the whole experience had been very positive: “Wherever the workers went they found the great majority of women in favour of the vote, and of being on a footing with men in every respect.”

Canvassing for the monster petition was her first experience of directly soliciting support for the suffrage. It taught her how to think on her feet and present a persuasive argument, and clearly. In the end, the monster petition collected more than 30,000 signatures. It was almost 260m long, so that several attendants were needed to carry it into Victoria’s legislative chamber. The organisers had high hopes for its success, but Munro went back on his word.

Even though the petition failed in its primary object, it had far-reaching effects. So many women had pledged their support for the vote that they could no longer be ignored by government or the press. The Victorian petition also encouraged suffragists in other states, especially in NSW, to intensify the work that many were already doing. Another step forward seemed to be South Australia’s granting of the colonial vote to its women in 1894.

Women in Goldstein’s home state recognised the need for a central organisation enabling all pro-suffrage groups to speak with a united voice, and one was promulgated by Annette Bear-Crawford. With Isabella and Vida Goldstein and Constance Stone, she established the United Council for Woman Suffrage, made up of representatives from each of the groups concerned with gaining the suffrage and improving the welfare of women and children.

Despite this, and even with a united group of women, the next few years in pursuit of the Victorian vote could fairly be described as dispiriting. Bills giving women the state vote were introduced into the Victorian parliament in 1894, 1895 and 1896: all were defeated in the upper house.

A fine example of the treatment the women received was the reception given to a deputation from the UCWS on September 6, 1898. More than 100 women supporters of the franchise crowded into parliament’s Queen’s Hall. They had to wait for almost an hour while members of the Legislative Council chatted among themselves and drank champagne, then Lowe and Bear-Crawford were summoned to another room to present their case. They had hardly started speaking when they were interrupted by “low jests and idiotic exclamations such as, ‘Who’ll mind the babies?’, ‘Pah! New women!’ and others not fit to print”.

Lowe and Bear-Crawford kept their tempers and dignity, but doing so was clearly something of an effort. Meanwhile, the women staying behind in the Queen’s Hall were joined by members of council. One man actually said to two of the younger women: “You girls, you don’t want the vote, you want … something else” with a “leering pause”. One of the women told him what she thought of him, and he “slunk off like a whipped mongrel”. None of the disgusted women was in the least surprised when once again the suffrage bill failed to pass the upper house.

In November, Bear-Crawford left for England to attend the Women’s International Congress.

In June 1899 came the shattering news that Bear-Crawford was dead — of pneumonia, in London, aged only 46. Goldstein and her colleagues were determined that the best way to honour Bear-Crawford’s legacy was to make sure Victorian women won the right to vote. With renewed energy they put up another woman suffrage bill in the second half of 1899. Goldstein was in charge. But this was the sixth time a woman suffrage bill had come before the Victorian parliament, and its opponents were ready. The first colony to embark upon a campaign for woman suffrage still had not granted it after 16 years.

This is an edited extract from

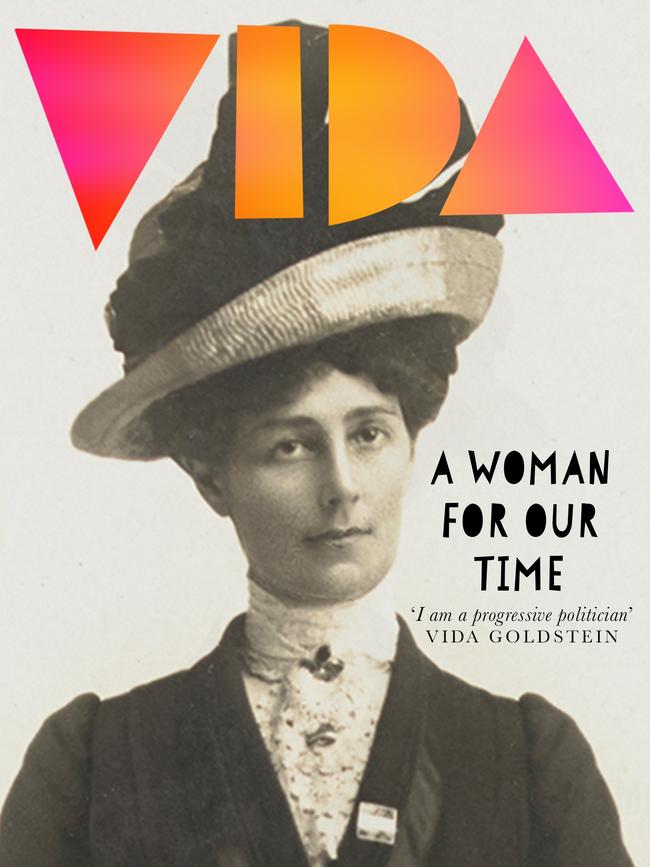

Vida: A Woman for Our Times

by Jacqueline Kent (Viking), out Wednesday.