The landmark endeavour that shook up the world

250 years ago, James Cook’s landfall at Botany Bay ushered in the birth of modern Australia.

There were two meanings James Cook could have drawn from the name of his battered and indefatigable vessel, Endeavour. Two hemispheres of thinking for a man who was sailing deep into a geographical hemisphere that remained terrifyingly unknown. The first meaning spoke of the endeavour laid before him by King George III: to observe and report on the transit of Venus and then to sail southward to find a continent that existed in imagination but not in ink. An attempt at something truly grand. A bold plan of action. A most remarkable endeavour.

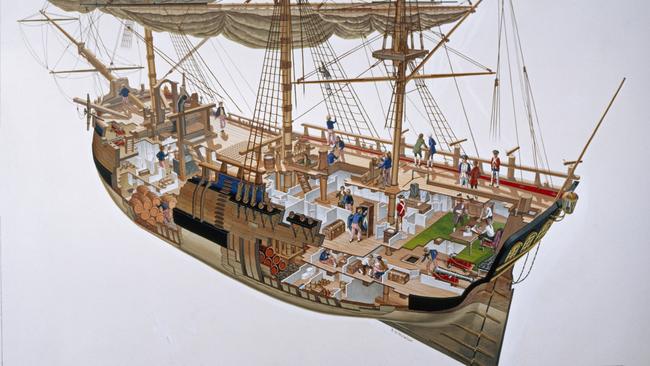

The second meaning spoke of deeper things. Heart things. Courage things. It spoke of the will to exert oneself. The urge to strive for greater understanding, of the world and of ourselves. To navigate the extreme and document the impossible. To sail a frumpy-bottomed coal boat on an unparalleled three-year voyage of discovery, carrying 94 people and 18 months of provisions, across a distance of 30,000 miles. To explore. To enlighten. To endeavour.

On Wednesday, April 29, our nation will commemorate the 250th anniversary of the day Cook made landfall at Botany Bay. Across the coming week we will recognise and reflect on the birth of modern Australia. A perilous endeavour of a different kind, some would say, in a nation divided between those who see Cook’s epic voyage of discovery as the foundation stone that the thriving multicultural melting pot that is our modern Australia was built upon and those who see that historic Botany Bay landfall as the first chapter in the story of Aboriginal dispossession.

These are treacherous waters to navigate but we are, collectively, endeavouring to find our way through. To find our greater understanding. To find our common ground between British ships and native shorelines. It was only three years ago that we woke to reports of vandals spray-painting slurs across city statues of Cook. These acts of vandalism spoke as much about the hurt that Cook represents for many Australians as they did about an alarming lack of understanding of Cook’s contributions to our world and the compassion and care with which he walked on to the sands of Botany Bay that fateful day.

This is a titan of exploration and achievement who we remember this week. This is a man possessed of a rare enlightenment that followed him to every corner of the globe. This is a man of breathtaking courage who, by the end of the journey in which he reached our shimmering shores, redefined what we humans knew of mathematics, navigation, geology, geography, botany, psychology, nutrition, astronomy, medicine, cartography and languages. This is a man who found and charted half a world that half of the world did not know. We don’t have to heroise this man and we don’t have to glorify him but we should damn well remember him; in statues, in books, in schools and most certainly in week-long 250th anniversaries. And as we recall the thrilling, edge-of-the-seat, nailbiting, against-all-odds story of Endeavour, we also should recall the oral histories and the campfire histories of indigenous Australians and the story of autumn 1770 as remembered by those who watched from the shore as that unflagging vessel made its way up this vast island’s east coast.

Cook’s instructions from his king that day on Botany Bay were clear: “You are likewise to observe the Genius, Temper, Disposition and Number of the Natives, if there be any, and endeavour by all proper means to cultivate a Friendship and Alliance with them, making them presents of such Trifles as they may Value, inviting them to Traffick, and Shewing them every kind of Civility and Regard.”

Cook was cautious that day as his pinnace approached the shoreline. Dangerous encounters on the shorelines of New Zealand were fresh in his memory. He saw two natives with spears, an older man and a younger man, at the edge of the water suggesting through their language and their gestures that Cook and the men in the pinnace — including legendary botanist Joseph Banks — would do best to row back to the wide-bottomed coal boat bobbing behind them.

Cook wrote in his journal: “We then threw them some nails, beads ashore which they took up and seem’d not ill pleased with in so much that I thought that they beckon’d to us to come ashore but in this we were mistaken for as soon as we put the boat in they again came to oppose us, upon which I fired a musket between the two which had no other effect than to make them retire back where bundles of their darts lay and one of them took up a stone and threw at us which caused my firing a second musket load with small shott and although’ some of the shott struck the man yet it had no other effect than to make him lay hold of a Shield or target to defend himself. Emmediatly after this we landed which we had no sooner done than they throw’d two darts at us. This obliged me to fire a third shott soon after which they both made off, but not in such haste but what we might have taken one, but Mr Banks being of opinion that the darts were poisoned made me cautious how I advanced into the woods.”

Hardly the warmest of welcomes and perfectly understandable behaviour from the men on shore who were most likely accustomed to strangers making respectful prior arrangements before crossing into their country.

Such miscommunications weighed heavily on Cook. His incredibly detailed Endeavour journal is filled with moments where he’s regretting the impact of his arrival on island communities, be it from unintended slights of native leaders or the possibility of his men spreading STDs to native women. The man who so rarely shared his emotions shared most profoundly when writing of these moments.

This week is a chance for us all to rewind to April 1770 and drill deeper into these events that had such dramatic ripple effects on who we are in April 2020.

As expected, anniversary plans have been drastically altered by the grip of COVID-19 but there are still many valuable ways to explore both sides of this story this week.

The National Museum of Australia, the Australian National Maritime Museum and the National Library of Australia all offer online resources and exhibitions that build on the growing “view from the ship, view from the shore” approach to recalling the Endeavour voyage. The National Museum’s online exhibition, Endeavour Voyage, for just one example, explores the 126 days Cook and his crew travelled up the east coast of Australia, from Point Hicks in southern Victoria to Cape York, Queensland.

They have worked tirelessly to collaborate with indigenous communities right along that east coast to uncover and share with the world the stories of the descendants of those who looked out from their homelands to see that trusty coal carrier pushing along the sea.

They are sometimes heartbreaking and sometimes heartening stories and they are helping us to find that sense of understanding, connection and human betterment that defined every mile of Cook’s most remarkable endeavour.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout