The inside story of the quiet battle of Martin Place

In the dying days of the Fraser Coalition government, in the closing months of 1982, the government and the Reserve Bank went to war.

In the dying days of the Fraser Coalition government, in the closing months of 1982, the government and the Reserve Bank went to war.

This extraordinary story – the only case in the 65-year existence of the RBA, of direct, extended, conflict between political government and the nation’s central bank – has never been told.

Yes, it was a very polite war, played out mostly in very proper communications between RBA governor – two governors actually, as it was initiated just as one was retiring – and treasurer.

So, it ran rather than raged for more than three months, through three RBA board meetings, with the RBA remaining resolute in refusing to bow to the government’s demand.

It was above all a secret war.

It was not played out in public then. And the fact that it ever took place has remained all-but totally unknown and certainly untold in the 42 years since.

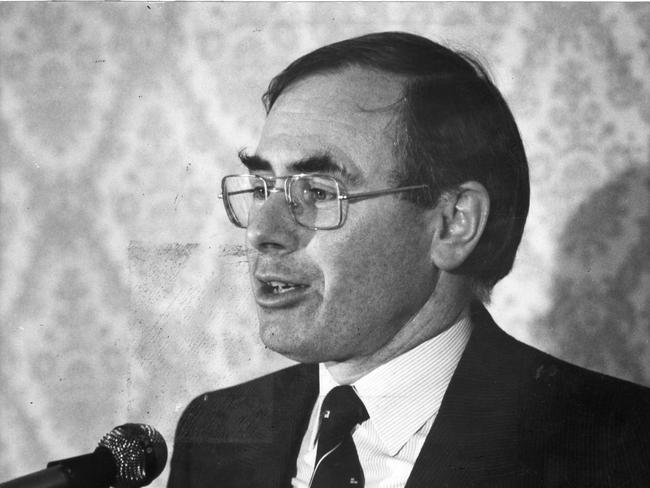

The then treasurer – and later of course, prime minister – John Howard effectively declared war by publicly asking the RBA, in his 1982 budget speech, to pump money into home lending.

He did so, despite having already been explicitly, privately, and repeatedly, told by the RBA governor Sir Harold – Harry – Knight that such a request would almost certainly be rejected.

And that going public with the request would spark a “civil war” between the government and the RBA.

Back then, budgets were held in the middle of cold Canberra winters, not as now in May. Or, increasingly, in election years, March.

The war would climax, as so often happens with momentous decisions by the RBA, on Melbourne Cup Day, in the RBA building at the top of Martin Place in Sydney.

The tension at that meeting would be temporarily eased, though, when the new RBA governor, Knight’s successor, Robert – Bob – Johnston, put deliberations on hold for a few minutes, and, as he noted in his personal papers, had a TV set wheeled in for board members to watch the race.

A week after that meeting, Treasurer Howard would end the war, effectively conceding defeat, when he publicly announced he had “deferred” the government’s request.

Through the entire three months of mounting crisis, the only public indication of what was unfolding were those two statements from Treasurer Howard.

The first, in August, making the “request”, the second in November, “deferring” it.

The RBA itself made no public comment at any stage.

Back then public statements of any kind from the RBA were rare.

Indeed, the public didn’t even know when or indeed if RBA board meetings were even being held, far less what was being discussed. There was no public schedule of meetings, either before or after.

And again, there were no post-meeting announcements of any decisions taken, like we get today with interest rates.

Speeches from RBA governors were rare. Contact with the media, formal or informal, even rarer.

Governors did not appear before the Senate and House committees to be cross-examined, like current RBA governor Michele Bullock was, last month.

But we are now able to tell, for the first time, in fine unfolding detail through a nearly four-month period of mounting crisis, what went on inside the RBA, as it refused to bow to the government.

The saga has been documented from internal RBA documents that have never been publicly released.

These include papers provided to the board members ahead of meetings, board decisions that were not made public at the time, or since, correspondence between Treasurer and RBA Governor, notes of conversations between Treasurer and Governor, Governor and Treasury Secretary, Governor and board members, and so on.

They are documents that the RBA has released from its archives, to The Weekend Australian, following our request.

Nearly a half-century on, this is not only an exercise in exposing to the light of day, for the first time, a very significant episode in the history of governance of Australia.

It also plays directly into the proposed reforms of the RBA from the current Albanese-Chalmers government.

The most controversial reform proposal is abolition of the right of the Treasurer to overrule an RBA decision. The so-called Section 11 power.

There have been calls for the Treasurer to overrule RBA rate hikes. Or indeed, to even use Section 11 to order the RBA to cut rates.

Two former RBA governors, Ian Macfarlane and Bernie Fraser, along with former treasurer Peter Costello, have argued vehemently that the Section 11 power should be retained.

Even though, through the entire 65-year history of the RBA, it has never been used by any government, either Coalition or Labor.

But in 1982, it came close, very close, to being triggered.

Stunningly, not by the Treasurer, using it to overrule an RBA decision.

But by the RBA in reverse – effectively challenging the Treasurer to formally, and publicly, order it to do what the government wanted. And which the RBA, refused to do.

And thereby explode it all into the public arena. Something that neither governor – Johnston or Knight – wanted.

And nor, even more obviously, Howard.

For as the then about-to-retire Governor Knight, pleaded in a private note to Treasurer Howard, right at the start, in mid-August.

“There are no winners in a civil war (between a government and the country’s central bank).”

While three months later, as exactly such a civil war reached its climax, his successor, Johnston, would note: “I did not think we should look upon Section 11 action in a relaxed way”.

But, as he went on in his note, if we refused the government’s request, “if we were forced through Section 11”, the reasons for our decision must one way or another be stated publicly.

They never were. Section 11 was not triggered. Treasurer Howard blinked. Just days later, he backed off.

How the crisis was triggered

What was arguably the greatest crisis in the history of the RBA was accentuated by two things.

First was the way it straddled those two RBA governors.

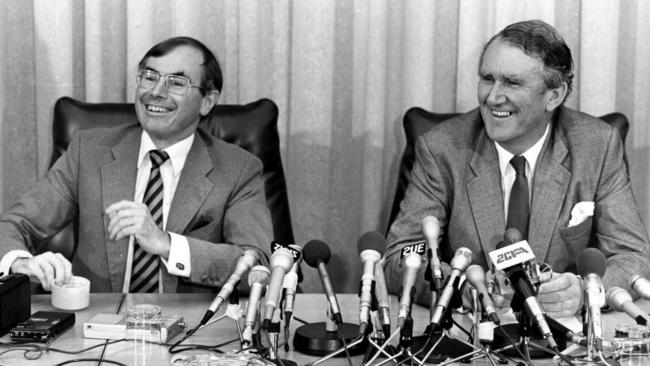

It started – it was kicked off by Treasurer Howard – just as Knight was retiring, and Johnston, appointed of course by Howard, was moving into the job.

Indeed, the formal request from Howard for a major policy change by the RBA, arrived on Johnston’s desk on the third day of his term.

Johnston was an unusual appointment. For the first time, a deputy governor – at the time, Don Sanders – had not been elevated to succeed the retiring governor.

Howard had plucked Johnston from the next rank of RBA executives, because he shared Howard’s determination to deregulate the financial system.

This was something that would only come to its full flowering, just a year later, under Johnston and another, Labor, treasurer, Paul Keating, of course.

Adding yet another layer was the extraordinary role that then treasury secretary John Stone played, as is revealed in the correspondence.

Stone was of course, as head of Treasury, Howard’s primary policy adviser. He was also, the specific link between Howard and Johnston.

Indeed, he was the person who conveyed Howard’s formal request to Johnston, first by phone, and then in writing.

But he was of course also a member of that very RBA board, which had to decide whether to say yea or nay. And as the internal RBA documents show, Stone was vehemently opposed to his own Treasurer’s request.

And what exactly did the government, conveyed via Treasurer Howard and Stone, want the RBA to do?

It wanted the RBA to make a special release of bank funds held at the RBA, back to the banks, but requiring the money be directed into housing loans.

Ah, the more things change, the more they stay the same, in property-obsessed Australia; and with incumbent politicians petrified of a borrower voting backlash.

Back in 1982 the Fraser-Howard government was in a full-on panic about both soaring home loan interest rates and the supply of funds from the banks for home loans.

The RBA and bank finance in 1982 were very different to today’s reality.

This was the pre-Keating time of very tight shared Government and RBA control and regulation of the financial system.

Yes, we were counting down, though, through the initial deregulation measures already started by Howard.

These would culminate in Keating’s full deregulation of the financial system, the floating of the Australian dollar, and the entry of foreign banks.

But in 1982 the RBA still directly controlled – but controlled, together with the government - the interest rate charged by banks on home loans.

In mid-1982 the RBA had raised the maximum rate banks could charge on home loans – and so effectively the actual rate banks charged, as they always charged the maximum - from 12.5 to 13.5 per cent.

But as the correspondence reveals for the first time, earlier in the year the government had actually overruled the RBA, when it had argued for a further rate rise.

In those days, interest rates were announced by the RBA, but changes were decided after discussions between the RBA, Treasury and Treasurer.

At that time, the RBA had gone along with the government. There’d been no talk of Section 11.

But it had clearly made the relevant RBA Governor - Knight - ‘sensitive’ to Treasurer Howard’s new politically-driven “request”, especially when it was to be made publicly in his budget speech.

Bank home loan rates, then and now, were central to the RBA’s fight against inflation.

But whereas now inflation is rising by something over 3 per cent over a full year, in 1982 it was leaping by over 3 per cent every three months – well into double digits on an annual basis.

Unlike today, back in 1982 the RBA still directly controlled how much money banks had to lend. For everything, not just housing. And it was this that Howard targeted.

The banks were required to hold a fixed percentage of their assets in government securities (their LGS ratio) and to lodge a percentage of their assets directly with the RBA.

This was their so-called SRDs - Statutory Reserve Deposits.

Treasurer Howard formally asked the RBA to release one percentage point of SRDs back to the banks, but to also mandate they lent the money – around $300m – for and only for home buying.

This would be additional to their existing level of home loans.

In those days, when even $100,000 properties were extremely rare – properties that sell today for $1m plus cost $20,000 to $30,000 then – that would buy a lot of houses.

And all the money would be for owner-occupier home lending. Back then the savings and state banks did not lend to investors.

The crisis was formally triggered on August 16, when, as the RBA documents show, treasury secretary Stone formally telexed new Governor Johnston.

“I refer to our telephone conversation a few minutes ago. There follows the text which I read out to you”.

“The government has decided to ask the Reserve Bank of Australia to consider making a release of one percentage point from the Statutory Reserve Deposits.”

Howard would publicly announce the request in his budget speech one day later; in doing so, effectively declaring war on the RBA.

That statement by Howard in his budget speech, and a second statement, three months later on November 9, that the government had “decided to defer for the time being its request”, were the only things the public were told at the time. Or indeed since.

Apart that is, from what the RBA obliquely recorded, nearly one year later, in its annual report for the 1982-83 year, under the heading “Some difficulties for policy”.

The RBA noted that the board had been “reluctant” to agree to this request for the SRD release from the government.

These views were “put to the government”.

The board “welcomed” the Treasurer’s deferral announcement in November.

Those relatively anodyne words papered over three months of high drama, as the RBA went right to the brink, in refusing the government’s request.

A refusal that was maintained through the three board meetings: September, October and the climactic Cup Day one.

This stand-off between the government and the RBA was utterly unprecedented. It had never happened before, and equally, has never happened since.

We can now reveal exactly what went on inside the RBA and between Governor – two governors – and Treasurer as they moved from the “request” in August to its “deferral” in November.

Howard goes public

While Howard went public with his request on August 17, he had actually first floated the idea with the about-to-retire Governor Knight, three weeks earlier in late-July.

Knight’s response had been then immediate and absolutely unequivocal. No.

In a very detailed note to Howard, dated July 30, Knight forensically dismantled any logic in trying to use an SRD release to provide money for home loans.

He finished by saying: the use of SRDs would be both an “inappropriate mechanism” and “unacceptable as an element of Reserve Bank policy”.

“The Bank staff would have severe difficulty in putting such a proposal to the board, and the board would be unlikely to proceed with it.”

That should have been the end of it. It wasn’t.

Four days later, Howard phoned Knight twice to press the government’s case for the SRD release. Howard told Knight that the cabinet had formally decided to ask the RBA to make the release.

On the same day, Knight formally responded to Howard with another detailed note.

From time to time, Knight wrote, sources outside the RBA had seen the SRD balances as an attractive “pot” from which to get some spending money, including for housing.

“This note conveys to you my reasons for concluding that it cannot come from SRDs”.

Knight formally repeated that bank staff would have “severe difficulty” in putting such a proposal; the board would be “unlikely to proceed with it”.

On the very same day Stone messaged Knight, referring to the first detailed rejection of the proposal that Knight had sent to Howard on July 30.

“I read my copy of that note over the weekend and I simply wish to send you my congratulations on it,” the Treasury secretary wrote. His attitude to his own Treasurer’s request was clear and unambiguous.

On August 12 – one day before his retirement – Knight was phoned by Howard about the SRD request, Knight recorded in a memorandum.

Howard asked whether, in the ordinary course, this would be a matter that would come up at a meeting of the RBA board.

I told him, Knight wrote, that the next meeting was on September 7. I would not be chairing it.

But “I thought it likely that, the chairman (his successor as Governor, Johnston) might see it as appropriate to let the board know of the request and the RBA’s response (his already stated rejection).”

“Unless there was a further initiative from Canberra, my own assessment is that might well be as far as the matter would be carried with the board”.

He was actually, very accurately, presaging, how the board, under his successor, would behave over the next three months.

Not issue a formal rejection, even privately to Howard – in those days there was no way the RBA would have made such a rejection public – but simply find it “difficult”.

In their conversation of August 12, according to Knight’s note to file, Howard did ask him whether he had a personal reading on how the board might view our exchanges.

My response, again, Knight wrote, was that it was likely that directors would be “firmly aligned with the position taken in the bank’s note to him.”

Mr Howard then asked – hypothetically – what I thought would be the board’s attitude if his budget speech referred to the matter having been “touched on” with the RBA.

Knight responded that the budget speech, on August 17, would be before the board had even heard of these exchanges and any government request. Directors would only be told at the next meeting on September 7.

I told the treasurer, Knight noted, that that such a mention would be “distinctly inimical to any prospect of the Board contemplating the kind of action ministers had in view”.

In other words: announce it publicly in your budget speech and by doing so, you will immediately kill its prospects.

“I made it clear again that I thought it unlikely in any case that the board would be willing to go any distance along this road”, Knight wrote.

Howard’s budget speech

That same day, at 5.50pm, Howard phoned Knight again, to tell him that after a meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee of cabinet, he felt himself under an obligation to say something in the budget speech about the SRD matter.

According to Knight’s note, Howard said he was aiming to frame what he would say, in a manner that would be “least offensive to the Bank and the board”.

He asked me, Knight added, whether I would be willing to “bend my mind to help him find such words”.

Knight noted that he then moved to remind the Treasurer of earlier negotiations with the banks over housing finance.

At that time, according to Knight, the Treasurer – “prompted by advice other than from the RBA” – had publicly mentioned policies, including SRDs, which the RBA board saw as being within “its statutory field of authority”.

At that time, the media had quite widely presented the matter as one where the Treasurer had initiated the decisions that were taken to boost funding for housing, Knight said to Howard.

“This sequence of events had been carefully noted at the time by the board,” Knight rather tartly added, in his note of the conversation.

Therefore – and this was clearly a very strong message from Knight to Howard – the RBA board had been made “quite sensitive to the subject of intrusion by the executive on powers committed by the Parliament to the Bank board.”

I further told the treasurer, Knight noted, that “I wanted him to be aware that reference of the kind he was contemplating would be a step towards a highly explosive situation.”

The Bank board comprised men of considerable substance, he said. Knight thought it likely their reaction to the move of the kind the Treasurer was considering would be a “very strong one indeed”.

Knight told Howard he would consider what the Treasurer was putting to him. He would respond the next day.

But, he then added, he could not foreshadow whether his response would be the form of words Howard was looking for. Or a “different response”.

The following day, his last as Governor, Knight sent a detailed two-page note to Howard. It was another strong and unambiguous rejection.

Knight said that if the government wanted to pump money into housing, the way to do it was directly, out of the budget, the way the Whitam Labor Government had done it in 1974.

He added that he “understood” that Howard’s Treasury head, Stone, was going to give him, Howard, a copy of the relevant (Labor) ministerial speech from that year, 1974.

That indicated again the joint opposition – of Governor and Treasury Secretary – to the government’s request for the SRD release to fund more home lending.

Knight discussed at length why the RBA did not want to ease policy at this time. But he said he would not seek to counsel the government against acting “within the government’s area of authority”.

Those words were underlined for emphasis in Knight’s note to Howard.

Knight further noted the government’s refusal, earlier in the year, to allow bank home loan interest rates to rise beyond the 13.5 per cent.

Knight added, that was something that if it had happened, would have enabled the banks to have raised more money for home loans by raising their deposit rates and thereby have attracted more funds for on-lending.

This was in itself an intriguing reference, which the correspondence, although indirectly, formally reveals this for the first time.

Today of course, the basic interest rate in the economy is set exclusively by the RBA.

But in 1982, while the RBA announced rate changes, the basic home loan rate – and indeed the whole range of interest rates across the economy – were decided after discussions between the RBA, Treasury and Treasurer.

Back in 1982, the RBA had gone along with the Government on the home loan rate ceiling. There had been no talk of Section 11.

But it had clearly made Governor Knight ‘sensitive’ to the new politically-driven request, especially when it was to be made publicly in the budget speech.

In his note to Howard, Knight repeated that using the SRDs would be inappropriate and unacceptable to the RBA

And further, that the board, if approached, would point to the 1974 road – under the Whitlam Labor government as the “proper means open to the Government”.

In extraordinarily strong words, Knight went on.

“Giving public notice of the Government’s approach would, in my view, set the scene for conflict, inherently publicly, between (on the one hand) the men of conscience who are on the board; administering their act under the Parliament; and (on the other hand) the Government.”

“Over the past thirty years, I have observed a number of such public conflicts between Governments and central banks, and in the process, consequent material harm to the community.”

“There are no winners in a civil war.”

Knight went on that, nevertheless, the proposition that Howard’s cabinet colleagues favoured, could be put to the RBA board for consideration.

Indeed, a very early special meeting of the board could be convened – obviously, by his successor.

But, “the particular point I press is that the matter be kept private until it has been fully explored.” He added.

Knight went on to say that he understood the collective obligations that Howard felt as a member of cabinet. But there were also the individual obligations undertaken when “one accepts office as a Minister of the Crown”.

“I wish there were no need to offer you such strong counsel to deflect your colleagues from their disposition to make public their decision to press – on my estimation, ineffectively and certainly damagingly – to effect their proper purposes by the wrong means,” he concluded.

The correspondence shows that Stone was also working feverishly – and as it quickly turned out, also ineffectively – to stop the Treasurer going public.

Stone’s phone call

On the morning of August 16 – the very same day, that Stone would later be formally conveying the decision by the Treasurer to go public in his budget speech – Stone phoned the new governor, Johnston.

Stone wanted to “bring us up to date about the SRD proposal”, Johnston noted.

He assumed, Johnston went on, and I confirmed, that “we had heard nothing since the (previous) Governor’s message to the Treasurer”, three days earlier, on Friday August 13.

Stone told Johnston that he had tried to persuade the Treasurer to hold out “until the last possible moment” about saying anything about SRD action, with the hope that the matter might be reconsidered in cabinet today.

But in the event, Stone told Johnston, Howard had told Treasury officials on the Sunday (August 15) that a passage in the budget speech should be regarded as a fait accompli, and that “further discussion with bis cabinet colleagues would be pointless”.

Stone told Johnston that he had tried again that Monday morning – August 16 – in conversation with the Treasurer, but to no effect.

The Treasurer said, according to Stone, that he did not agree with the government’s proposed action but he took it now as beyond discussion.

Johnston asked Stone whether anything had been said about timing.

No, responded Stone.

Stone then speculated whether, if it became clear we were headed to an early election, the Bank might hold off any decision on the grounds it would be improper to act with an election in the offing.

In late 1982 Fraser had planned an early election, but the plans collapsed when he was hospitalised with a back injury.

The thereby delayed ‘drovers dog’ election the following March would of course propel Bob Hawke into The Lodge and Keating into Howard’s Treasurer’s office.

Tuesday night, Howard made the request public; and government and RBA were at war.

Nothing further was said publicly. Or even it appears, for a few weeks, privately between Martin Place and Canberra.

The documents

Ahead of the September 7 board meeting, directors were given a series of documents.

These included the text of the Government’s formal request, originally conveyed by Stone to Johnston back on August 16, and which the Treasurer now asked be put “formally to your board at its meeting on September 7”.

“The proposal was discussed with your predecessor prior to the budget”, Howard’s formal note to Johnston went. “As you no doubt know, Sir Harold expressed his strong concern about the proposal”.

The government recognised and respected this general view expressed by Sir Harold, Howard’s letter went on.

But the government was deeply concerned that the availability of housing finance had deteriorated, to the point of having serious consequences for the dwelling construction industry and home ownership aspirations.

Does that sound an all-too familiar lament, 42 years on?

Along with Howard’s formal note, board members were given a detailed paper on the state of housing and housing finance, including a discussion of the SRD proposal.

This reaffirmed an SRD release would not be appropriate and it would not actually work as the government hoped.

At the September 7 board meeting, directors authorised the Governor to tell the Treasurer that it had “difficulty” reconciling his request both with monetary policy overall, and the specific role of SRDs.

This was the word, “difficulty”, that the board would stick with through the next two months. And on to its annual report the following year: the RBA’s only public comment then, or in the 42 years since.

Not the more definite “rejection”.

The board also authorised the Governor to express a “willingness to explore” with the Treasurer possible alternatives. None of this was made public, of course, then or since.

Directors were also told for the first time about the exchanges between the previous Governor, Knight, and the Treasurer, and given copies of them.

An initial draft of an accompanying note to these documents, from the RBA Secretary’s department, had a sentence: “We would prefer these papers not leave the boardroom.”

This though was scribbled out and not included on the actual note delivered to directors.

The next day, Governor Johnston met the acting Treasurer Senator Guilfoyle – Howard was away – as RBA Governors did after every board meeting to debrief the Treasurer.

He told her the board saw “difficulties” with the SRD proposal, and thought that alternatives might be explored with the Treasurer.

If Howard had thought he would get a more sympathetic response from the new governor, he was clearly to be disappointed.

Although the reference to “alternatives” showed Johnston was more prepared than Knight to try to find a different path that would meet the government’s economic – and, frankly, political – objectives.

On September 14, Johnston formally communicated all that to Howard in a letter.

“I shall of course, be available to discuss these matters when convenient to you”, Johnston’s letter concluded.

But there was no immediate response from Howard. There is no record of any further discussion between Treasurer and Governor, ahead of the next board meeting on October 5.

At this meeting, the only formal reference to the Government’s request was that the board “noted” the Governor’s letter to the Treasurer of September 14.

“No formal response to the letter had yet been received nor has the Treasurer otherwise sought to discuss the matter with the Bank,” directors were told.

Three days after the meeting, on October 8, Johnston told Howard “we have been thinking of alternative paths to achieve higher lending for housing”.

Johnston suggested direct talks with the banks - “on an RBA-to-bank basis”, on a low key basis”, “in strict confidence”, and of course “without commitment”.

Three days later Howard spoke to the deputy-governor, Sanders, giving Johnston’s suggestion the green light.

The RBA spent October negotiating with the banks to get them to agree to maintain a higher level of home lending.

This set the scene for a climactic week in the first week of November, first on Cup Day, Tuesday November 2; and then on Friday November 5 – a day that would prove to be arguably the most dramatic in the entire history of the RBA.

Governor Johnston brought to the formal RBA board meeting on the Tuesday something of a deal agreed by the banks.

First, the banks formally supported the RBA, that SRD releases should not be made to provide funds for lending to specific sectors of the community.

But the banks said they shared the concerns of both the government and the RBA that it was not in the interests of economic stability that home lending drop sharply.

Provided savings bank deposits continued to grow at a sufficient pace, the banks said they were reasonably confident they would be able to provide an extra $300m of home loan approvals above the annualised level of lending they had done in the March 1982 quarter.

The RBA staff had assessed the bank proposal as likely to achieve a reasonable outcome to the government’s initiative in relation to housing finance, although it “might fall a little short of its (the government’s) expectations”.

On that basis, Johnston recommended to the board that it authorise the Governor to put to the Treasurer the bank proposal as an alternative to an SRD release.

It’s now lost in time whether it was before or after directors watched Gurners Lane complete the Cups double, beating the champion David Hains-owned Kingston Town, but they duly endorsed that recommendation.

The following day, Wednesday November 3, Johnston formally wrote Howard a lengthy two-page letter putting the banks proposal.

The letter specifically drew attention to the fact that the banks and the RBA were both firmly united in the view that it would be inappropriate to use SRDs to fund home lending.

Johnston stressed that the banks had made it clear that they did not see scope to increase home lending in the period to end-March 1983, greater than the sum ($400m) of increased lending they had earlier in 1982 already agreed with the Treasurer.

Johnston added that “we stand ready to take up with the (State government owned) savings banks not party to this proposal, the case for acting along lines similar to the major banks.”

He concluded his letter: “If the banks’ proposal is acceptable to the government, they would be agreeable to your making an early announcement.”

Johnston clearly did not want to get into a direct, far less a direct public, confrontation with the treasurer.

Nothing was recorded as happening on the Thursday. Then Johnson’s – and the board’s - truly climactic Friday, started with Howard ringing him at 9.30am.

Howard told Johnston that he could not recommend the banks proposal as an appropriate alternative to the government’s SRD request.

He could not be sure, Johnston noted, that he could “dress up” a proposal for the banks to lend even $400m extra from their savings banks, far less the lower figure of $300m, as an acceptable proposal for Cabinet.

But. Johnston recorded, Howard said, he would “think about it”.

Howard went on, according to Johnston’s note for his file, that in the end it came down to a matter of “whether or not the Reserve Bank board refused to make the (SRD) release.”

He would “like to have a formal answer from me at our meeting this afternoon.”

This was the scheduled, regular, post-RBA meeting between Treasurer and Governor, for the Governor to brief the Treasurer, formally, separately, from the Treasury secretary.

In effect, Howard was asking Johnston to finally commit one way or the other on a Section 11 trigger.

The Treasurer, according to Johnston’s note of their morning conversation, went on to say that he “did not welcome the steps he was putting to me but he had an obligation to see that the wishes of the Government were carried out”.

In those pre-Zoom days, an immediate crisis RBA board meeting – just three days after the Cup Day meeting - was not possible.

So Johnston set about phoning all the board members, staggered 20 minutes apart. The first call was made at 11.20am the last at 2.20pm, followed by a call to John Milne, the AN Z CEO and chairman of the Australian Bankers Association (ABA).

After those calls, at his meeting in the afternoon with the Treasurer, Johnston clearly did not give the Treasurer the “formal answer” he wanted.

Indeed, all Johnston’s memo of the meeting says about the crisis is that “there was some discussion on this matter”.

But separately, and potently, he noted that the Treasurer “drew out” from him that the board was concerned that any easing of liquidity conditions in the economy would require either bond sales by the RBA “or an SRD call”.

Johnston told Howard at their face-to-face meeting that, “except that demand for credit had weakened, an SRD call would be coming into consideration very soon.”

Running down to what would be a March election, these were clearly words Howard did not want to hear.

That the banks would maintain a higher level of home lending; but they would do so only AFTER March, and so, after the election.

And that, in a worst case, the RBA could even be calling bank funds INTO SRDs, certainly not releasing them for anything, far less for home lending.

From the notes in the files, and through that last climactic day, Friday November 5, Johnston was not only canvassing his own directors on the government’s demand for an answer.

Johnston also kept talking directly to the major bank CEOs in search of a compromise. In a desperate effort to get what the government wanted: a firm commitment to substantially boost home lending.

He asked the ANZ CEO, Milne: would the banks be prepared to set aside funds from their LGS – the ratio that sits next to SRDs – for home lending?

No, responded Milne, the banks had already rejected that alternative, proposed to them at some earlier point by the RBA deputy-governor Sanders. They would only do something like that “on a directed basis”.

What about another proposal that the major bank savings bank offshoots firmly committed to raise their proposed lending, Johnston asked?

On that Milne said he had not been able to “get around the Wales (the Bank of New South Wales, now Westpac) board”.

“They were feeling very annoyed and bitter at the Treasurer over the transactions tax,” Milne told Johnston.

After speaking directly himself to the Wales CEO Bob White on the Friday afternoon – apparently unsuccessfully – Johnston made his final phone call to Milne.

Milne told him that his bank, the ANZ could provide more home lending, along with two other major banks; so that would be three providing their shares of increased home lending.

So, it came down to something never seen before or since in the 65 years of the RBA: a Governor canvassing each board member separately and directly, on whether to defy the government and trigger Section 11.

Including asking, as a member of that board, the Treasurer’s own top policy adviser, Treasury secretary Stone.

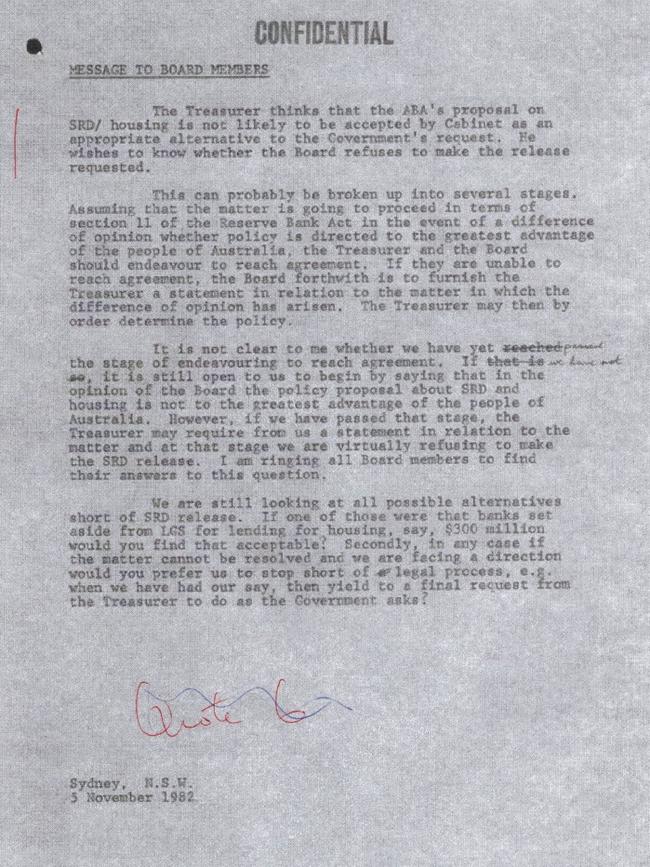

Johnston had each board member faxed, telexed or otherwise sent a one-page brief, the like of which I could pretty confidently say, would have been unique in the RBA’s history.

The brief informed directors that the Treasurer thinks the ABA proposal was not likely to be accepted by cabinet as an appropriate alternative to the Government’s request.

“He wishes to know whether the board refuses to make the release requested,” Johnston’s note began.

“Assuming that the matter is going to proceed in terms of section 11 of the Reserve Bank Act in the event of a difference of opinion whether policy is directed to the greatest advantage of the people of Australia, the Treasurer and the Board should endeavour to reach agreement.”

“If they are unable to reach agreement, the board forthwith is to furnish the Treasurer a statement in relation to the matter in which the difference of opinion has arisen. The Treasurer may then by order determine the policy.”

Johnston wrote, though, it was not clear to him, whether we had yet “passed” – in the draft copy, he had crossed out his original word “reached” - the stage of endeavouring to reach agreement.

If we had not, it was still open to the board to state the policy proposal about SRD and housing was “not to the greatest advantage of the people of Australia”.

But if we had passed that stage, the Treasurer may require from us a statement, and at that stage we are “virtually refusing to make the SRD release,” his note told directors.

He further noted – indirectly referencing his frantic series of calls directly to bank CEOs – that the RBA was still looking at all possible alternatives to an SRD release.

He informed them that one of those was for the banks to set aside funds for housing from LGS – the proposal that ABA chairman Milne would dismiss in his later phone call to Johnston.

Finally, Johnston asked the directors: if the matter cannot be resolved, and we are facing a direction, would you prefer us to stop short of legal process?

That is to say: “when we have had our say, then yield to a final request from the Treasurer to do as the government asks?”

In a memorandum dated Monday November 8, Johnston detailed the comments that had been made by each director in their phone conversations of the Friday.

Businessman Sir Samuel Burston said he thought the bank had made its point and he did not want to stand the government up.

In a second phone call, Johnston noted, Sir Samuel said that he personally did not want to see the RBA go to Section 11 procedures.

Gordon Jackson, the CEO of CSR, did not think an SRD release was appropriate at this time for general reasons. He also though it inappropriate for SRD funds to be directed into a special purpose.

Jackson also made a second call to Johnston. He stated more firmly to Johnston that an SRD release would be inappropriate at this time for any reason.

But he also hoped that it would not be necessary to proceed to a disagreement with Government involving Section 11. He wanted further alternatives explored.

Professor Trevor Swan – the only economist apart from the RBA duo and Stone on the board – said that if others wanted to go ahead with Section 11, he would join in that.

Interestingly Swan also referred to – unexplained – previous confrontations with the Treasurer; including a discussion with the board at which the Treasurer had been present.

At that meeting, the previous governor (Knight) had said to the Treasurer, according to Swan, that he supposed we, the RBA, would go along with the Treasurer’s demand,

But, Swan said, Knight added to Howard, that we, the RBA, would have to make known publicly that we did so reluctantly.

At that, according to Swan, the Treasurer “changed his mind”.

Swan emphasised that in the present case we should make it plain in public that we complied (if that was what we decided) reluctantly.

Swan also made a second call to Johnston, with the suggested text of a letter to the Treasurer, saying we would comply but would have to go public with the reasons for our reluctance.

Jack Davenport, another CEO of a major company, said the RBA was confronted with an awful predicament. We could not answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ at this stage.

“Whilst he felt strongly that the proposed action by the government was wrong, he did not want to buck the government.”

Hugh Morgan, the CEO of major mining company Western Mining, subsequently taken over by BHP, thought that confrontation was an “appalling prospect”.

But “there was no logic in the government’s proposal” and to accede to it involved “loss of face and public respect”.

Morgan, according to Johnston’s note, thought the board’s integrity was involved.

“If we were left with no option but to accept the government’s view in this matter, we should say publicly that we regard their request as having no merit.”

Stone reaffirmed that he thought the action proposed by the government was quite inappropriate. But that we should not as a board answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the Treasurer’s question at present.

On his personal position, Stone said, Johnston noted, that as a board member he had no doubt that the correct answer was “no”.

But second, was his role as Treasury secretary. The minister had made plain the government’s request and he could not very well ignore it.

I would therefore, Stone said “have to abstain from any decision not to accede.” Johnston noted.

In a second memorandum, also dated Monday November 8, Johnston detailed further conversations with board members on that day, Monday.

Davenport had met the Treasurer at a function over the weekend, and the Treasurer had said he had had a “very friendly’” discussion with the RBA on Friday afternoon. And that the Treasurer was confident he “had the solution”.

Davenport repeated to Johnston that if the matter came to a direction from the Treasurer, “the government is the government” and we cut it off before Section 11 was involved.

Morgan also phoned. He had also been speaking over the weekend with a “Cabinet attendee”.

That unnamed person said the RBA should be relaxed; the government was really aiming at the banks.

If the RBA went through with Section 11 proceedings, then - according to what Morgan said he had been told - “bully for them”. The government would not be upset with the RBA.

Johnston noted he wasn’t fully clear on the points Morgan was making. But he noted that he told Morgan that he did not think we could look upon Section 11 action in a “relaxed way”.

The RBA should expect its reasons for demurring from carrying out the Government’s request should be stated publicly, Johnston went on.

If we were forced through Section 11, the RBAs reasons would be tabled in parliament.

If we stopped short of Section 11, but complied with the request, we, the RBA, should state the reasons for our reluctance publicly.

That Monday would prove to be the high point of the – at that point, still unresolved – crisis.

The RBA board would not be forced to formally “answer” the government’s demand.

For a 11.30am on the Tuesday morning, November 9, John Hewson – Howard’s principal economic adviser, and later, as Coalition leader, the loser of the ‘unlosable election’ of 1993 – phoned Johnston with a “compromise proposal”.

Could the RBA get the banks to agree to lift the 1982-83 and 1983-84 extra home lending figures to $500m for each?

Hewson phoned a second time, Johnston recorded, to say the Treasurer had scaled it down to just the $500m in 1983-84.

Howard would tell the Monetary Policy Committee of Cabinet, Hewson told Johnston, that monetary conditions had changed and the SRD request would be “put in abeyance for a year or so”.

Johnston phoned the proposal through to Jack Booth, one of the big bank CEOs who was that day temporarily acting ABA chairman in Milne’s absence.

He then embarked on a further flurry of call with both Booth and individual bank CEOs.

“Around lunch time,” Johnston noted, he called the Treasurer’s office in Canberra.

He was unable to speak to either Howard or Hewson directly. But he told one of Howard’s staff that, as yet, none of the banks was prepared to give a firm undertaking on increased home lending to the amount sought.

But if “all went well” the banks would commit to “use their best endeavours” to get the figure up to the government requested $500m in 1983-84.

But, Johnston stressed, this was not be construed by the government as a promise.

More calls followed in the afternoon between Johnston and the banks; and finally, at 6.15pm, the banks delivered to him a form of words to be on-passed to the Treasurer.

With the drop in demand for home loans, the banks said, they had difficulty in guaranteeing extra lending beyond continuation of the extra $400m figure.

But if factors changed, the banks would “use their best endeavours” to lift to $500m.

Howard’s statement

That Tuesday night, Howard issued his statement – only the second, made at any stage through the four months of building crisis, by either the government or the RBA - announcing the government had decided to “defer for the time being” the SRD request.

The crisis was over. The RBA didn’t have to and never did give a formal response to the request made just under three months earlier.

In his statement Howard also announced the promised extra home loan lending from the banks.

Howard finished, however, by saying that if more money was required for housing over and above that now to become available, the government “will not hesitate to proceed with the (SRD) request to the Reserve Bank”.

The following day, Howard phoned Johnston, who recorded Howard saying that he hoped the outcome he had announced was satisfactory to the RBA.

The Treasurer sought to downplay the “postponement aspect,” Johnston noted, by saying that the whole subject would quickly fade from the public mind.

I told the Treasurer, Johnston noted, that the matter had ended as well as could be hoped.

I told him I thought the promised extra bank lending was feasible; we at the RBA could not have gone along with a totally irresponsible proposal.

Johnston wrote that he added, that the RBA had “not at any stage made any public comment” on the government’s SRD proposal.

And that, further, I did not intend to “depart from that position now”.

The same day Johnston dispatched identical letters to all the RBA directors, including of course Stone, noting the government’s decision to “put aside its request”.

“I am most grateful for the support and advice you and colleagues gave in the negotiations leading to the present outcome,” his letter concluded.

This was not, though, to be the last word.

First, the RBA board would formally note, at its December board meeting, the way the matter had been concluded.

But more interestingly and more potently, the day before the December board meeting, the RBA’s banking and finance department prepared an “Aide Memoire” for the Governor.

The subject: SRD Release for Housing.

“We all recognise that the episode raised some important questions of principle,” it began.

You (the Governor) might like to consider having a general statement of these principles, and of the board’s views on special purpose SRD releases, “on the record and before the Treasurer.”

This would be a means of “gently seeking to discourager possible similar future approaches”.

A statement has been drafted and is available to be discussed if board members consider such an initiative to be useful in the present climate.

This more detailed statement, attached to the ‘Aide’, was headed “Note for Treasurer”.

It clinically dismantled the arguments for any form of special purpose release from SRDs, and rejected the idea categorically.

It finishes that “any departure” from the general principle is likely to create a precedent “which could become very uncomfortable for the board’s efficient execution of its charter”.

There is no record in the RBA archives of the statement ever being dispatched to the Treasurer. Or whether Johnston raised it with Howard at their regular post-meeting debrief, after the December RBA board meeting.

In any event, both Treasurer (Howard) and SRDs would soon disappear.

The Treasurer, from that office the following March; although he would of course return to the much bigger prime ministerial office 13 years later.

SRDs, in the Keating-Johnston financial deregulation of the 1980s, with RBA control of monetary policy and so, indirectly, bank lending, reduced purely – only – to its official cash interest rate.

Which in turn led to the RBA raising its rate to 18 per cent at the end of the 1980s, helping deliver Treasurer Keating’s recession “we (supposedly) had to have”. And much else, after that.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout