The fresh dangers of Fortress Australia

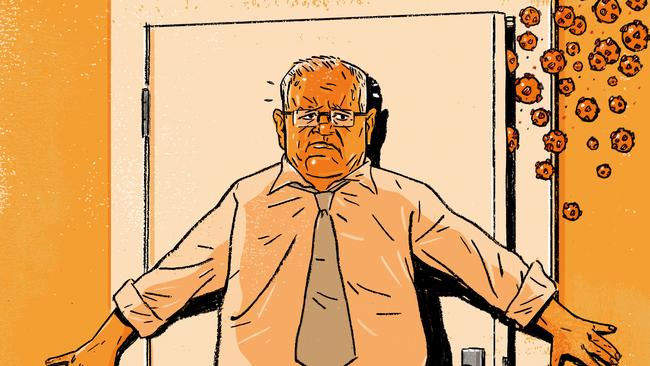

COVID success now threatens our economic recovery in race the Morrison government pretends is not happening.

Australia’s global “leader of the pack” performance last year in suppressing COVID-19 is threatened in the recovery phase where the dominant test of progress is the vaccination rate, with Australia badly lacking in this global race — a race the Morrison government pretends is not happening.

The EU is preparing to allow vaccinated holiday-makers to travel for the northern summer tourist season underpinned by an EU vaccine passport. In Britain 37 million have had a single shot and 20 million people, or 31 per cent of the population, are fully vaccinated.

The US is advancing towards herd immunity with 124 million Americans, or 38 per cent, fully vaccinated. As of this week a total of 60 per cent of Americans have received one dose of vaccine. At its current rate the US will reach the 75 per cent level in September-October. Senior US health official Anthony Fauci says once coverage hits the 70-85 per cent zone society can approach normalcy.

The Australian government may yet be vindicated but the risks are mounting. The iron law that governs Scott Morrison and Health Minister Greg Hunt is getting the health story right — if a nation stumbles on the health front then it stumbles on the economic reopening. Elite economic opinion and majority public sentiment are split in Australia with the Prime Minister — aware of the looming national election — conscious that allowing the virus to penetrate from abroad would be a health and electoral fiasco.

At present only 3.3 million out of 25 million Australians have had their first vaccine dose. The rollout has been plagued by supply problems with three-quarters of the current supply coming from the domestic CSL production line. The government’s decision last year on this facility now looms as pivotal.

Polling evidence points to public complacency with anecdotal reports that many people see no compelling reason to be vaccinated. Australia’s success against COVID has become a complacency trap. The government correctly warns about the resurgent virus in many countries, with fresh outbreaks testing Singapore, South Korea, Japan, Thailand and Taiwan.

Countries leading the vaccination rates are Israel, United Arab Emirates, Chile, Britain, the US, Mongolia and Hungary, a mixed bag. There is a global race for full economic recovery in a “living with COVID” vaccinated society where success goes to those nations best able to combat the virus as it mutates. While Europe and the US are ahead of Australia in the vaccination rollout their societies are behind in terms of the “normality test” for civil society.

The goal from Morrison and Hunt remains: by year’s end there will be the opportunity for all Australians who choose to be vaccinated. This is a steep task. While vaccine supply will expand from July, the big rollout will be in the final quarter of the year. The public anxiety at that time will be intense. Anybody who thinks Morrison will call an election as part of that mix needs to calm down and reassess.

This week Morrison was in relentless campaigning mood, doubling down on the transformed nature of Liberal Party policy, as represented by the budget, with his government pledged to build a $600m gas-fired power plant in NSW’s Hunter Valley and putting $2.3bn into saving the nation’s two remaining oil refineries, proof of an aggressive brand of government intervention that rips up past pro-market Liberal orthodoxy.

Morrison’s aggression, like the budget, will deliver electoral dividends in the short term but will store up policy and fiscal sustainability risks down the track. Yet his tactics to further penetrate Labor’s base vote and brand the ALP as addicted to higher tax seem to be working. This week the Labor Party signalled its inclination to oppose the stage three tax cuts for middle and high-income earners and opposed the Hunter Valley gas plant, sound in policy terms but inevitably exposing the ALP’s internal split over energy.

At the same time, Morrison struggles with the politics of recovery and the balance between health and economy. He must negotiate between the public’s obsession with Fortress Australia and closed borders on one hand and the need to signal some pathway to economic opening after the vaccination process is more advanced — witness his support this week for more liberalised rules for vaccinated people in the case of future lockdowns.

The politics are fraught and dangerous. Newspoll showed a massive 73-21 per cent majority for keeping the international border shut “at least” until the middle of next year as opposed to liberalisation after vaccination. The hermit-like prejudice of the majority is a huge recovery risk. Morrison knows he must stay with closed borders until after the autumn 2022 election — yet he cannot ignore the momentum for recovery.

Australian Industry Group chief executive Innes Willox called on federal and state governments to develop plans for borders to be reopened. “People lack the incentive to vaccinate while the borders remain relatively sealed,” Willox said, calling for a “balance of risk” approach. He branded closed borders a “killer blow” for tourism and accommodation related industry.

This follows the earlier searching critique of the recovery strategy by Business Council of Australia chief executive Jennifer Westacott that the budget’s forecasts on future economic growth and private investment didn’t do the job. She warned of a “false dawn” because the investment trend was not apparent and Australia was not sending “the right messages to the rest of the world that we are open for business”.

This week’s fall in unemployment to 5.5 per cent vindicating the government’s phase out of JobKeeper and contradicting Labor’s dire warnings also opens the door to a different emerging problem — labour shortages with ongoing closed borders, population growth at a rock bottom 0.2 per cent in 2021-22 and with immigration only gradually returning from mid-next year.

Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy made clear this week that full recovery meant “a return to open international borders and stable, well-balanced migration” since skilled working-age migrants delivered an economic dividend, raising workforce participation and likely productivity growth.

The government knows where the country must go. “It’s not one day the borders are open, one day the borders are closed,” Morrison said. “That’s not how it works. There’s a sliding sort of scale here. We’re working on the next steps. It’s not safe to take those next steps right now.”

Yet the criteria governing safety must be changed. That’s the entire point of vaccination. If vaccination cannot change the rules of the game then its purpose is busted. The notion of one case of community transmission being a catastrophe that provokes a lockdown cannot endure. Morrison made the logical case that vaccinated people — in the case of future state-imposed lockdowns — be allowed freedom of movement.

That’s sensible. But any suggestion of a domestic passport, creating two classes of Australians and shattering the idea of a united country, would be a step too far. The premiers were all over the place in their reaction to Morrison. As usual NSW leader Gladys Berejiklian was far ahead, saying people should be able to move around the country whether or not they were vaccinated. She repudiated any notion of an internal passport or a dual-track model.

But Morrison believed his proposal was “something that Australians would support and I think it recognises the reality that states and territories, from time to time, will be making decisions which will restrict movements of Australians across the country”.

This is potentially alarming — that premiers will keep playing the populist card, keep using their lockdown powers, keep their populations on edge and, in the process, constitute a populist threat to Morrison that he cannot confront or defy because the fortress mentality has taken root.

This confirms the states, NSW aside, as risks to economic recovery and to Morrison’s political strategy since Queensland and Western Australia — where the Coalition is dominant at the federal level — are basic to his re-election. Morrison cannot get into a border war with Annastacia Palaszczuk or Mark McGowan.

Morrison will raise the issue at national cabinet. “I think it’s a reasonable thing to work through,” he said. Sources told Inquirer that the Prime Minister was not proposing an internal passport but merely that in the operating of state permit systems there should be a free pass for vaccinated people.

Morrison shuns making specific commitments. He won’t nominate a proportion of the population necessary for herd immunity. He warns that nations with advanced rollouts are seeing a “levelling out” at about 60 per cent of their population. He rejects enhanced advertising campaigns because they cannot substitute for lack of supply. He plays down the differences between Australia and other nations — they had to rush because they had higher death rates.

The truth is the government’s messaging in the current situation is confused and fraying about the edges. Australia excelled in the first phase of suppressing the virus. But the second phase is different: it is finding a regime and a public psychology that can manage the virus with minimum social and economic disruption.

The Treasury secretary in his speech this week to Australian Business Economists offered a cogent exposition of the reasons for an expanded fiscal policy and made a detailed defence of the economy’s capacity to meet the debt serving task caused by the increase in net debt to reach 40.9 per cent of GDP in 2025.

Kennedy drew attention to the critical factor — the government decided on “structural increases in spending”, notably for aged care, the National Disability Insurance Scheme and JobSeeker payments. He addressed the paradox of the budget saying the government was “on track to stabilise and reduce debt” even while in the first and expansionary phase of its fiscal policy.

Yet the long-run fiscal implications are contested — none more strongly than by Macroeconomics chief economist Stephen Anthony, who told Inquirer: “The structural deficit by the middle of next decade is in excess of 6 per cent of GDP. The current budget position is unsustainable. Debt will begin rising above the capacity of the economy. The budget perpetuates the notion that spending equals structural reform, which is obviously wrong.”

Anthony’s critique goes to strategy. It goes to the debate briefly addressed last year. Should Morrison and Josh Frydenberg have focused their efforts on the singular task of fighting the recession and promoting the recovery — which they have done with success — or should have used the crisis to engage in large-scale economic reform?

“The COVID crisis and the royal commission into aged care were opportunities to fix things,” Anthony said. “But we haven’t done that. We’ve spent a fortune without any capital improvement to the structure of the economy. That’s why there will be no reform dividend. That’s why this poor generation to come will be loaded with a policy mess plus a big structural budget deficit, the likes of which no Labor government has ever left this country.

“It’s ironic and unprecedented. At that very moment last year there were people writing — including myself — ‘never waste a crisis’ and this is drummed into you at Treasury. Crises don’t come along too often, they’re really expensive, and you have to take the opportunity they present when there’s political goodwill. But if you just try to take advantage of the situation you can do a lot of fiscal wrecking and I think that’s what has happened here.

“The reason we will have a structural budget crisis by the middle of the next decade is because we have a treasurer who lacked the capacity to seize the opportunity that presented itself last March and use the crisis to restructure the tax system and other benefit payments. I don’t want to be unfair but there is a lack of big-picture vision in this budget.”

The Morrison government is increasingly entangled in a trade-off between economics and politics — its budget seeks to power-drive economic recovery and jobs with huge fiscal support yet its protectionist politics excuse closed borders and a slow vaccine rollout and put a priority on populist caution.