The first Syrian in space was brave man who spoke up for his country

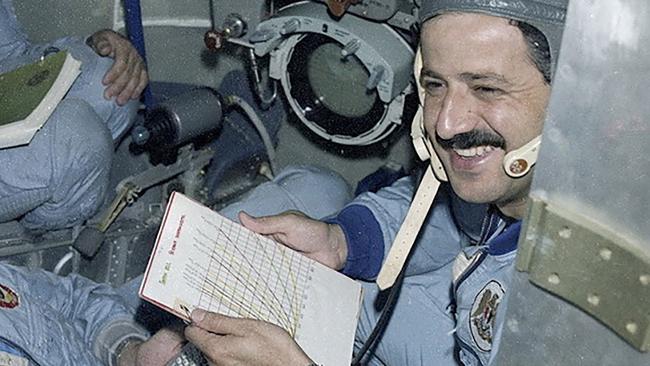

Syrian Muhammed Faris was the first genuine Arab spaceman, and he proved his courage again during his country’s civil war.

OBITUARY

Muhammed Ahmed Faris

Aviator and cosmonaut. Born Aleppo, Syria, May 26, 1951; died Gaziantep, Turkey, April 19, aged 72.

Theodore von Karman was another of those Hungarian maths geniuses who fled rising Nazism in Europe and migrated to the US where he had a terrific impact on technological innovation as America became the world’s most powerful and innovative nation.

He worked on some of the problems needing to be solved before mankind could face its final frontier. In recognition of his achievements, the accepted boundary between Earth and space is called the Karman line – 100km above us.

Until last month, just 676 people had crossed it. And 19 of them have been killed getting there or returning home. Right now there are 10 people in space: a SpaceX crew of four, a Soyuz team of three, and three Chinese astronauts at the Tiangong space station where they have been for 184 days.

Space travellers are in an exclusive club. And within it are more select subsets, such as the 75 women who have made the journey. History records that the first Arab in space – there have been six and they are known as najmonauts (najm being Arabic for star) – was Sultan bin Salman Al Saud.

His dad is the king of Saudi Arabia and Sultan flew under the old mate’s act as the US let him aboard the 18th space shuttle flight as a payload specialist, a definition that allows NASA to take up barely trained outsiders such as journalists and teachers – “everybody but the walking wounded”, as one NASA boss said. Perhaps Sultan had to do a daily headcount each morning to make sure no one had not been sucked out a porthole in the dark.

The first genuine Arab najmonaut was Syrian fighter pilot Muhammed Faris, a colonel in the Syrian Air Force when he was chosen in 1985 to train with Moscow’s cosmonaut program. It helped that he was a fluent Russian speaker and he graduated quickly through steps to be sent to space.

Faris flew to the Mir space station in July 1987, arriving in one Soyuz craft and returning in another after eight days, and secretly created a record: “I brought with me a vial carrying soil from Damascus,” he told a reporter years later. It was the first Earth dirt in space.

He had been up there with legendary cosmonaut Alexei Leonov who, in 1965, had become the first human to “walk” in space.

But things turned sour, not that Faris understood this at the time, when, during a live phone call with Syrian president Hafez al-Assad that was broadcast throughout his homeland, Assad asked what Faris could see from up there. “I see my beloved country, I see it wonderful and beautiful as it truly is.”

These were not the words Assad’s team had prepared for the occasion, which Faris never divulged but almost certainly would have sung Hafez’s praises. Hafez thought Faris had sought attention for himself, a sometimes deadly sin in that dictatorship. Back in Syria days later, Faris received a hero’s welcome, but an angry Hafez refused to hang a medal around Faris’s neck, merely handing it to him. Hafez also ignored appeals from Syria’s second most famous man to launch a space program so others might follow him. That’s the last thing Hafez wanted.

When Hafez died in 2000, his son Bashar al-Assad took over and, briefly, Syrians hoped for a better future under the Western-educated ophthalmologist – but summary executions became common and many perceived enemies of the dictatorship disappeared in brutal waves of ethnic cleansing.

When the 2011 Arab Spring spilt over into Syria sparking mass demonstrations, Bashar’s vicious, cruel crackdowns were condemned around the world. Faris bravely sided with the revolutionaries, but emerging from the quiet suburbs of Aleppo placed his family in danger.

He sent his children to different friends’ houses around the city and made plans to flee. One morning in 2012 he had them assemble at one address and Faris, his wife and children were driven towards Turkey as Bashar’s helicopter gunships patrolled Aleppo’s skies.

With the help of the Free Syrian Army they crossed into Turkey a few days later and moved to Istanbul, living among its significant Syrian expat community.

Like most of them, he imagined returning to a changed Syria one day and settling again in Aleppo – one of the world’s oldest cities. And this brave holder of an Order of Lenin always spoke up against Russia and its unforgivable support for Bashar’s murderous regime.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout