The extraordinary link between a 1961 massacre and a missing yacht

In 1961, a family was murdered off Florida by a scheming psychopath. The film Dead Calm was based on those events. Did they play out for real off Sydney in 1988?

In the annals of improbability, the narrative thread that binds the murder of a family in the Florida Straits in 1961, legendary filmmaker Orson Welles, the Australian movie Dead Calm that starred Sam Neill and Nicole Kidman, and a schooner that went missing off Sydney in 1988 is right up there. Indeed, it is barely believable.

The unlikely tale unravelled across three continents, touching base in Fort Lauderdale, the Bahamas, South Africa, Perth and Esperance, across the course of 26 years. Its final chapter has not yet been written, and may never.

It starts with one mystery and ends in another. But there is a lot of tale in between as this dark parcel is unwittingly passed from one family to the next.

Terry Jo Duperrault was 11 when Nicolaos Spachidakis, second officer on the Greek freighter Captain Theo, nearing the end of it 8000km trip from the Belgian port of Antwerp to Houston, Texas, spotted a white spot on the horizon. It was November 16, 1961. The ship was passing through deep waters west of the Bahamas.

At first he thought it might be a fishing dinghy, and there did appear to be a figure on it, but he reckoned it was too far out to sea.

He kept watch as the ship drew closer. His crew was astounded. Sitting atop a cork flotation device not 2m long and its disintegrating webbed canvas centre was Duperrault, badly sunburnt, dehydrated and surrounded by curious sharks. She waved weakly.

They lowered a dinghy, transferred her to their ship, slowly dabbed water around her mouth and gave her orange juice. Her eyes were unfocused. She could not stand. And she could not, or would not, speak. The ship’s captain, Stylianos Coutsodontis, asked who she was and what had happened. She gave a thumbs down sign and whispered “Bluebelle”. He called the coastguard.

Back on land the Bluebelle had been in the news. Its captain, Julian Harvey, 44, had been picked up in a life raft after, he claimed, the Bluebelle’s mast broke off in a storm, pierced the hull and quickly sunk it as it caught fire.

The boat had been chartered by optometrist Arthur Duperrault, Terry’s father, who was taking his family, wife Jean, and Terry’s siblings, Brian, 14, and Rene, 7, island-hopping around the Bahamas for a week or two, depending on how they all took to it.

Rene’s body was in Harvey’s life raft jacket. Harvey claimed it had floated by and he had tried to resuscitate the girl. Harvey’s new wife, his sixth, Mary Dene, also had been aboard as the cook.

As details in his story changed, other sailors queried why no one had reported the Bluebelle in flames. And the World War II bomber and decorated Korean War flying ace had history: a former wife had died when he drove off a bridge returning home from the movies. She was wife three – Joann – who, with her mother, drowned. A reportedly untroubled Harvey collected life insurance. He’d also lost two large sailing boats in accidents and profited from those as well.

While being questioned by the Miami coastguard – they had noticed what appeared to be scratches on his arms – news came through that there had been a survivor. Harvey was told and appeared shocked. That night he took his own life, leaving a note that read in part “I guess I either don’t like life or don’t know what to do with it” with instructions that he be buried at sea. He had recently take out a large life insurance policy for Dene. It is speculated he planned to killed her on the Bluebelle and throw her body overboard during the night. Maybe one of the family heard something and went to help.

The Duperraults had been on deck, but Terry had gone to bed below. She heard shots and shouts – her brother screaming “Help, Daddy, help!” – and went up to peek at what was happening. Harvey, with a gun, told her to get back down. Minutes later, the Bluebelle started to fill with water. Terry waited until it lapped at her mattress before retrieving the cork lifesaver and jumping into the dark waves. Adrift with no water, no food and no cover, she was not rescued for 84 hours.

Terry’s guiltless family was dead. So, too, the psychopath her father had hired for their holiday. And his unlucky wife. It was an extraordinary event and breathlessly reported for weeks as Terry recovered in hospital.

American author Charles Williams was well established as a crime-fiction writer and based his 1963 novel, Dead Calm, partly on those unthinkable events.

Screenwriter, actor and producer Welles – he’d become instantly famous years before when his too-lifelike radio adaptation of HG Wells’s War of the Worlds apparently had some listeners believing Earth was under attack by Martians – bought the film rights to Dead Calm and between 1966 and 1969 worked on a never-finished adaptation called The Deep.

Welles took interest in the story; like the Duperraults, he was from Wisconsin. He planned to act in it himself and offered roles to Charlton Heston and Peter O’Toole, who reportedly described Welles’s script for it as “beautiful”. (Welles was in Ireland in August 1931 on a forlorn attempt to establish himself as a painter. Instead he was so distracted by the pursuit of the “poor virgin ladies” there he “could hardly draw a breathe”. It is speculated that he was probably O’Toole’s biological father.) Welles fussed over The Deep but encountered financial problems. It remained a work in progress until its lead actor, Laurence Harvey, died in 1973 aged 45.

Australian director Phillip Noyce was given the book in 1984 by American producer Tony Bill – he had won an Academy award for The Sting – who also had shown interest in the story. Welles died in 1985 and about that time Noyce interested Mad Max filmmaker George Miller in it. Miller secured its rights and it was shot in the Whitsundays in 1987.

The story of a troubled, fearsome stranger found at sea rowing from a sinking ship in which everyone was dead took ideas from the book. Much of it was filmed using the South African-built yacht Stormvogel, line-honours champion of the 1965 Sydney to Hobart race. The film was released in April 1989 to mixed reviews, but The Australian’s film critic David Stratton liked it very much back then and reviewers have warmed to it since.

The film was in theatres when, on May 9 that year, a fisherman off the NSW Central Coast picked up a lifebuoy. When he wiped off some of the slime and barnacles he saw the name Patanela: Fremantle. A marine biologist examined the sea life still attached to it and reckoned it had been in the water no more than a month. Which was odd because the Patanela – which had set off on October 16, 1988, from Fremantle for Airlie Beach, where some of Dead Calm was filmed – had not been heard of since three calls to the Sydney-based Overseas Telecommunications Commission, based in Sydney’s Paddington, in the early hours of November 8.

On board the Patanela when it sailed was the owner, Perth businessman Alan Nicol, his skipper Ken Jones, Jones’s wife Noreen and their daughter, Ronalee. Also aboard were friends from Taree, John Blissett, 23, and Michael Calvin, 21. They had seen the 20m Patanela being readied in Fremantle and asked for crew positions.

The boat was on its way to serve as a charter from Airlie Beach. Not only had scenes from Dead Calm been filmed there but Calvin also had worked on the film, helping to build a replica of the Golden Plover that features in it.

On its way across the Great Australian Bight, they stopped to refuel at Port Lincoln, South Australia, where Ronalee and Nicol alighted to return home. What happened next is a mystery other than the calls to Sydney, the first at 12.58am on November 8, 1988, when conditions were overcast but, well, almost dead calm.

“I believe we’ve run out of fuel,” said a composed captain Jones, saying the Patanela was 11 nautical miles off Botany Bay. “We’ve hoisted our sails and were tacking out to the east … our intention is to tack out for a couple of hours, then tack back in. We may need some assistance in the morning to get back into Sydney Harbour.”

An hour later he called asking for a weather report and directions to Moruya, well south of there. The last call was barely audible with radio interference – odd if he were just off Sydney: “Three hundred kilometres south? Is it? South?” – then contact was lost.

Three days before, Calvin had called his father in Taree but managed only “G’day, Dad” before the line went dead. There has been dark suggestions one of other parties aboard planned to hijack the yacht, but these are absurd. Nonetheless, it is not uncommon for pirates to seize a boat and for it to be “rebirthed” elsewhere. Did Jones make those calls under duress? His family believes it uncharacteristically imprecise of him to say he “believed” he was out of fuel.

No ship or boat in the area at the time had signs of having collided with the Patanella. No flotsam was found.

On December 31, 2007, Sheryl Waideman and her husband, Gary, drove nine hours to Eucla, a dot tucked into the easternmost point of Western Australia where they camped for several days. They had never been before. “It’s very remote, but that’s what I like,” Sheryl said this week. “It was a stinking hot day.”

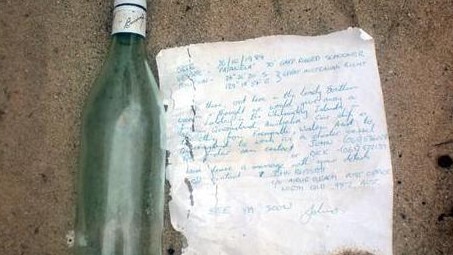

Walking along the beach she found a Bacardi rum bottle with a note in it. Back home, they opened the bottle and carefully retrieved a letter dated October 26, 1988. It read: “Hi there. Out here in the lonely Southern Ocean and thought we would give away a free holiday in the Whitsunday Islands in north Queensland, Australia. Our ship is travelling from Fremantle, Western Aust, to Queensland to work as a charter vessel.” It was written and signed by Blissett and gave the boat’s co-ordinates that placed it about 300km south of Eucla.

The Waidemans joked about their find and called the number. It didn’t answer. Days later they called again and Blissett’s mother Marj answered but thought it a scam and asked them to send a copy. She called back days later: “Yes, that’s definitely John’s writing. Definitely his signature.”

They travelled to Taree to hand the bottle and message to the Blissetts, who chose not be interviewed for this piece but asked that anyone with knowledge of the Patanela's fate contact authorities.

“It was quite a sad affair,” said Sheryl. “But we were both of the opinion that the letter proved the boys wanted to make it to Airlie Beach.” They had dinner with the Blissetts and Calvin’s mother (his father had died).

These days, Ronalee lives on the mid-north coast of WA and remains confident she knows what happened: “I think somebody’s boarded the boat and has probably killed them and taken it.”

She agrees with her brother that her dad, Ken, also a pilot, was careful and attended to detail. Her father had filmed and photographed the trip, and asked Ronalee if she wished to take these home. “I said no, Dad, it’s OK.”

She was with Calvin and Blissett when they wrote the note, which they all thought was a bit of fun as they cruised the Bight. “They were lovely boys.”

She thought something was amiss when she didn’t get flowers for her birthday: “I rang my brother to say something’s wrong, and he said he had the same feeling.”

But no search was mounted until it was too late. Interestingly, the discovery of the lifebuoy and it being so fresh in the water has never surprised her. She still hopes for an answer one day. “All along we said somebody’s got that boat.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout