The dangers of confecting a workplace rape crisis

We need to maintain high bars for serious misconduct – for the sake of women and men.

Here, in small print at the bottom of page 24 in a 132-page report, is a big story about how serious words – rape and sexual assault – are being refashioned to capture trivial actions, to inflate numbers and create the perception of a culture in crisis. A crisis which, if it truly existed, would demand money, people and empires.

It’s a story of what happens when zealotry takes hold. Worst of all, it’s a modern tale about feminism as melodrama, where women are treated as trauma cases ready to happen.

In a report released this month, the new parliamentary workplace support service (PWSS) records 30 reported instances under its most serious category of “rape/sexual assault, assault, sexual harassment, harassment, stalking or intimidation”.

Sexual assault is a very serious matter. Every workplace, including Parliament House, must have proper and safe processes to deal with such serious allegations. Perpetrators should be punished well beyond any workplace consequences. They should be punished by the criminal law. The desire to improve the workplace, especially for women, is an understandable one. For too long, workplaces turned a blind eye to even serious misbehaviour.

The agency was set up last year following a review by Sex Discrimination Commissioner Kate Jenkins to address the historical injustice where workplace misconduct was not taken seriously. At first glance, its initial report is shocking. It says that 9 per cent of cases the PWSS has managed since opening its doors, from October 1, 2023 until June 30, 2024, fell into the category of “rape/sexual assault, assault, sexual harassment, harassment, stalking and intimidation”.

What’s more shocking, however, is footnote 4. It says that “the sexual assault percentage may appear to be high because support staff take a trauma informed approach, and record incidents as described by the client. People use the expression ‘sexual assault’ to include a wide range of conduct, from feeling uncomfortable about how a person looked at them to what would be a traditional use of the word rape. It is likely that very few of those matters would actually be allegations of rape.”

Overcorrections are common, when our desire to fix things is done with passion and in haste. The pendulum, as we know, swings from one extreme to the other. By any logical measure, it is colossal overreach for a workplace agency to include a wayward look in the same category as sexual assault. Not as an unwelcome gesture. Not even as sexual harassment. But as sexual assault.

“Sexual assault” has a specific legal definition. It occurs when a person is forced, coerced, or tricked into sexual acts against their will or without their consent. A look, no matter how lascivious, cannot be sexual assault.

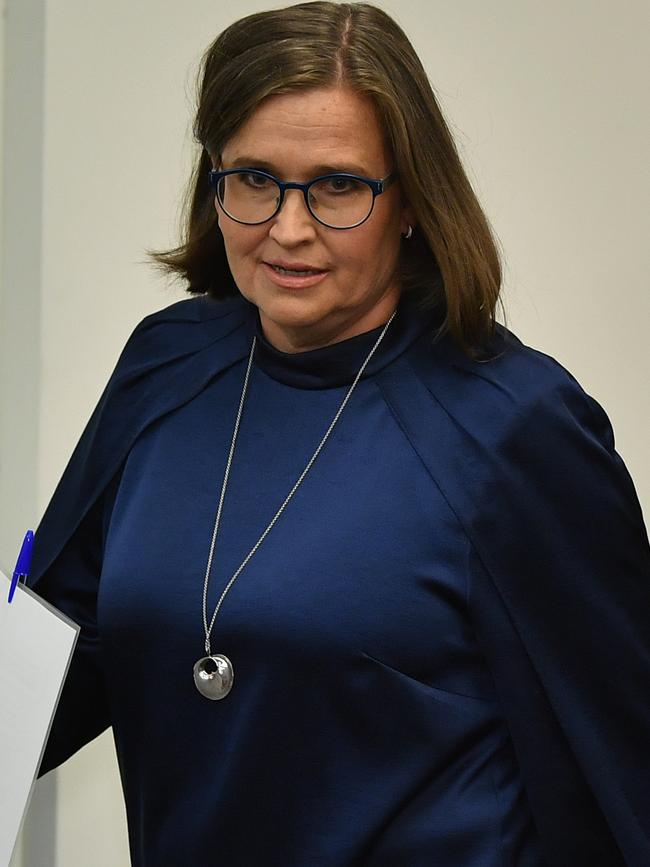

This first annual report from the PWSS, handed to the Albanese government on October 21, features a photo of chief executive Leonie McGregor, deputy CEO Kate Wandmaker, acting chief operating officer Leanne Martens and chief people officer Scott Mischkle. It has separate categories for “bullying” and “workplace conflict”.

Why didn’t this female-dominated leadership team create a distinct category for “looks that make a worker feel uncomfortable” when collecting data of cases it managed in its first year of operation?

That would be preferable to stripping rape and sexual assault of their proper and very serious meaning. There is nothing remotely “trauma informed” about that.

Perhaps the law of bureaucracies explains why PWSS did this. By their nature, bureaucrats nearly always want us to think they need more people, more offices, more money, more power. You can’t ask taxpayers for more money or resources unless you can argue you are already doing too much with too little. Just ask the ABC.

Inflated numbers of managed cases of “rape/sexual assault” for this new agency created a sense of crisis. Naturally, the 9 per cent figure of cases of rapes and sexual assaults attracted front-page headlines. “Report into toxic Canberra Culture”, blared the Sun-Herald last weekend. The higher the number of serious workplace cases managed by this agency, the more reason to keep funding it.

Inflating numbers, by defining down rape and sexual assault, might be good for business, but it’s unlikely to be good for women or men.

While no one should be made to feel uncomfortable from uninvited and unwelcome looks, overreach under cover of being “trauma informed” risks trivialising rape and sexual assault. If women are encouraged by this report to describe a lecherous look as a sexual assault, what words do they use to describe the real thing? And what will taxpayers and those who work at Parliament House make of the numbers in future reports?

A sure-fire way to encourage people not to take reports of sexual assault seriously is to turn the phrase into a catch-all for “a range of conduct” that doesn’t come close to being sexual assault.

Alas, this flawed first report from the PWSS is part of a pattern of similarly flawed reports that conflate the trivial with the serious to create a sense of crisis. Some years ago, the Australian Human Rights Commission’s Changing the Course report into sexual assault and sexual harassment at Australian universities was presented as evidence of widespread campus rape culture.

The report’s statistics on sexual harassment included students self-reporting about other students who stare, leer, make suggestive comments or jokes, ask intrusive questions about a person’s private life or appearance.

This ridiculous definition of sexual harassment ignores the real world of complicated, messy and delightful human interaction, where people flirt and joke and look at one another because that’s what happens when you’re attracted to someone.

Zealots always go too far. And so it was with campus rape culture activists. Australian universities can’t find, let alone respond to, anti-Semitism right under their nose, but they spent $1m of taxpayer money on a dodgy report that conflated trifling behaviour with sexual harassment.

In her 1992 book, Sex, Art and American Culture, feminist Camille Paglia predicted that the “feminist of the fin de siecle will be bawdy, streetwise and on the spot confrontational, in the prankish Sixties way”. Alas, a quarter way through the 21st century there is no sign of that sort of feminist. Today’s feminist flamethrowers are mostly overpaid government bureaucrats. Like other deep-state bureaucracies, they are untethered from real problems and real people.

The Workplace Gender Equality Agency is a prime example of taxpayer-funded empire-building on steroids, where dodgy data is gathered and women are infantilised, to justify this bureaucracy’s existence. This week, it presented new work showing one in four employers are not monitoring the prevalence of sexual harassment in their workplace. But is it any wonder that sexual harassment is not taken seriously, when serious behaviour is defined down to mean trivial things?

The new parliamentary support service agency is doing something far worse, by neutering the meaning of sexual assault. In no sensible world can this phrase be stretched from a glance to unwanted sexual intercourse.

We need to set firm and high bars for serious misconduct – for the sake of women and men. If we don’t do that, collecting data on sexual assault will be laughed out of school as meaningless. And places we work and interact with people will become impossible to navigate. It’s bad enough to be forced to walk on eggshells for fear of offending a fellow worker. Male employees at parliament – yes, we are talking mostly about men when discussing sexual assault and rape – are now on notice that they are one inappropriate look away from being folded into the same category as rapists in annual reports to government.

The PWSS was created with the stated purpose to “drive cultural change”. It’s doing that, in spades, in the wrong direction by trivialising rape and sexual assault. Given this was no accident, we’re entitled to ask whether dangerous zealotry has already taken hold in an agency that opened its doors for business just over a year ago.

Sometimes a footnote deserves to be a headline. That’s the case with footnote 4 in the first annual report from the new human resources agency established to change the culture in federal parliament.