The caliphate’s cubs want to come home

Khaled Sharrouf spent four years transforming his kids into villains of ISIS. It took their grandmother one hour of TV to take them back.

Khaled Sharrouf spent four years transforming his five children into propaganda villains of Islamic State. It took their grandmother just one hour of television to take them back.

“They deserve to come back here,’’ a tearful Karen Nettleton told the ABC’s Four Corners program. “They deserve to be here and happy and safe, and have food and be able to walk down the street, be normal.’’

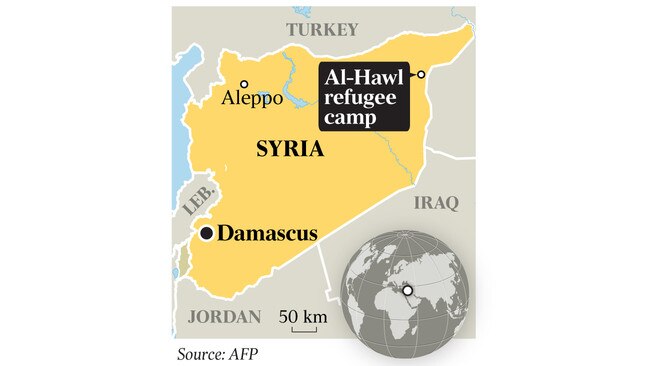

Nettleton’s quest to retrieve her grandchildren from Islamic State-controlled Syria, which culminated this week in an emotional reunion in front of TV cameras at al-Hawl refugee camp in the country’s north, has increased the pressure on the Morrison government to evacuate the family, or what’s left of it. The spectacle of an elderly grandma from the suburbs of Sydney traipsing through the mud of a Kurdish refugee camp plaintively calling for her grandkids has cast doubt on the government’s suggestion that the camp is a no-go zone for Australian officials.

If a little old lady can get there, why can’t the government?

It’s more complicated than that, of course. Journalists, and grandmas, are free to travel in a way Australian officials cannot. But since the collapse of the caliphate the government’s approach to Australians stranded in Syria has been to say and do as little as possible, publicly at least.

That may now change. The eldest of the Sharrouf children, 17-year-old Zaynab, is 7½ months pregnant. The odds of her safely delivering her baby in the putrid conditions of al-Hawl are not good. How will Australians react if the unthinkable happens?

Yesterday, Scott Morrison hinted work was afoot to assist the children, although he offered few details. ‘’We’ve been working with various international bodies on a range of these issues, (including) the International Red Cross,’’ the Prime Minister said. ‘’I made it very clear that no Australian would be put at risk in terms of going into what is a very dangerous part of the world, and that is the clear instructions that have been provided to officials.’’

Lowy Institute terrorism expert and Middle East specialist Rodger Shanahan says the most direct method of getting the Sharroufs out of Syria would be for the International Committee of the Red Cross to transport them across the border into Iraq and into the care of Australian consular staff.

“The ICRC work on both sides so they would have relations with the Syrian government. It’s a potentially neat option for the Australian government,’’ Shanahan tells Inquirer. Iraq is close to the camp and it has a functioning government with which Australia has good relations. The children could be cared for in Iraq and in time be repatriated. We will see.

On Four Corners, Nettleton said they had a government guarantee of any help needed “in getting the children back into society”, including deradicalisation. “Just because they’re last name is Sharrouf, doesn’t mean they are monsters,” she said. “Are my children a risk to Australia? — absolutely not. No way.”

Nettleton’s search for her grandchildren underscores a much larger problem, one that affects the dozens of Western countries whose citizens travelled to the caliphate, and which will probably require a collective response, such is its scale. There are about 73,000 people in the camps in northern Syria. The Sharroufs are among the 70-odd Australians authorities estimate made it to al-Hawl following the slow strangulation of the Islamic State’s self-styled “caliphate’’. Some are fighters, a few are wives but most, around 40, are children, like the Sharroufs. Their presence will be a standing challenge to whichever party crosses the line on May 18, as well as the Australian community as a whole, which will be asked to take back into its midst the small number of Australians who swore to destroy the very society they now seek to rejoin.

No Australian family better embodies those challenges than the Sharroufs. The five kids were taken into Syria by their mother, Anglo-Muslim convert Tara Nettleton, in 2014. A few months earlier their father, the convicted terrorist Khaled, had travelled to Syria with his friend Mohamed Elomar. For the next few years Zaynab, Hoda, Abdullah, Humzeh and Zarqawi became propaganda tools for their parents and for Islamic State. In 2014, The Australian published the now iconic picture of a young Abdullah holding the severed head of a Syrian official, an image that came to typify the depravity of Islamic State.

Then US secretary of state John Kerry called it “one of the most disturbing, stomach-turning, grotesque photos ever displayed’’.

Tara Nettleton died in 2015 and two years later Khaled was killed in an airstrike, along with his two eldest sons, 12-year-old Abdullah and 11-year-old Zarqawi. By then Zaynab had been married off to Elomar at age 13 and given him a child, Ayesha, now three years old.

When Elomar was killed, Zaynab remarried and bore a second child, Fatima, now two years old. Zaynab is said to be heavily pregnant with her third.

Shanahan says it is impossible to apply a blanket policy to the 70 Australians in Syria. The way you treat an Australian fighter will be different from the approach taken with their children.

‘’Each case has to be dealt with on its merits,’’ he says. “The Sharroufs are in unusual circumstances in that both parents are dead. We all know they were taken as kids. They have a family support network back in Australia. If you were going to get one group out, this would be it.’’

Other cases will not be so straightforward. Melbourne woman Zehra Duman is among the handful of Australians pleading with her country to take her back, or at least her children.

Duman was just 19 when she left for Syria in 2014. She married Mahmoud Abdullatif, a hard-partying Melbourne boy whose career as an Islamic State fighter ended abruptly when he was killed five weeks after the pair wed. Duman, now 24, says she’s had enough. Her two children are sick and malnourished, she can’t contact her family. She has no money. “I want to go back to my country,’’ Duman says. “I think everybody’s asking for that because I’m an Australian citizen.”

Unlike the Sharroufs, who were taken to Syria against their will, Duman’s pleas are unlikely to find much purchase among the 25 million Australians she set herself against when she joined Islamic State, an organisation that has waged war on liberal democracies across the globe.

But odds are she’ll end up back here anyway, either in a prison cell or, more likely, living in the community she once despised with the assistance of the state she not that long ago considered the enemy.

The camp at al-Hawl is run by the Syrian Democratic Forces. The SDF has made clear it wants countries such as Australia to take back their citizens. US President Donald Trump wants the same. In February, he tweeted bluntly that he expects Europeans, and one can assume Australians too, to clean up their own mess. ‘’The United States is asking Britain, France, Germany and other European allies to take back over 800 ISIS fighters that we captured in Syria and put them on trial. The Caliphate is ready to fall,” the tweet said. “The alternative is not a good one in that we will be forced to release them …’’

The Australian government is said to have very good intelligence on which of its citizens survived the carnage of Islamic State’s last days. The SDF, the mainly Kurdish militia that took Islamic State’s last redoubt of Baghouz and which now runs the camps, conducted detailed screenings of refugees before they entered. That information has been shared among coalition governments including the Australian government.

The problem of Islamic State fighters returning from the conflict is one authorities have been bracing for since the Syrian civil war began. And yet now that it is upon us there is a strange hiatus on how to proceed. Should any of the Australians stranded in Baghouz find their way home, a slew of state and federal committees set up to manage the return of Australians in Syria would swing into action.

But getting from al-Hawl, which is sovereign Syrian territory, to Iraq or Turkey is no easy thing. Much will depend on the patience of the SDF and how long it wants to maintain the camps. Of the 70-odd Australians, not all will come home. Some will stay abroad. The government’s insistence that the camps are no-go zones is not easily reconciled with the parade of journalists, aid workers and fixers who for months now have been moving freely through al-Hawl camp. Australians interviewed in al-Hawl have also spoken of contact with mysterious Australian officials, no doubt part of the army of foreign spies working to identify potential threats to national security.

But, as Shanahan points out, the issue is not so much one of physical security as of the legal footing for Australian officials operating abroad.

“There’s a difference between a journalist going into one of these camps and an Australian government official going into Syrian territory without permission from the Syrian government,’’ he says. “What are your rights to enter sovereign Syrian territory and start interviewing Australians?’’

One solution might be to persuade the SDF to take Australians held at al-Hawl into Iraq, but that option is not without complications either. ‘’You might get the Iraqis saying, ‘We want to prosecute them. They committed crimes in our country.’ ’’ If and when Australians do find their way out of al-Hawl, the first step for the Australian government would be to conduct a detailed risk assessment of the kind of threat they pose.

This would fall to a committee of senior officers drawn from the Australian Federal Police, ASIO, the Australian Secret Intelligence Service and other agencies. The committee’s task will be to assess the risk and craft a response.

That could mean prosecuting the adults with terrorism offences. The AFP has 29 arrest warrants for Australians in Syria, although a considerable number of those warrants apply to fighters who are almost certainly dead, like Khaled Sharrouf. Prosecuting the rest might prove harder than it seems.

Since 2014 the AFP has devoted most of its resources to investigating terrorist conspiracies on Australian soil. Relatively little attention has been paid to Australians in Syria, although recently that is said to have changed. Even where Islamic State fighters have been prolific on social media, posting trophy pictures of themselves brandishing weapons and urging the murder of infidels, it may prove difficult to attribute those statements definitively to them.

The evidence of their crimes is in Syria and hence hard to gather. What information police can cobble together might be inconclusive or difficult to verify.

Resolving the situation of Australian children could prove no less knotty. Most were born on Islamic State territory. Establishing their claim to Australian citizenship will first require ascertaining their parentage, something not easily done inside a refugee camp. The job of reintegrating them will fall largely to the states that control the health, welfare and housing services they will likely need.

This will be harder still depending on the status of their parents. For example, do you prosecute someone like Duman, who prima facie may be guilty of terrorism offences but is also the sole parent of two young children? Grappling with these questions will be a challenge for the authorities and the community. You’d like to think it will also be a challenge for returnees, who must make peace with the society they once betrayed.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout