The brutal boys’ home that created more crims than it cured

The Mount Penang Training School for Boys was touted as a bastion of reform. In reality, it was rife with torture and abuse.

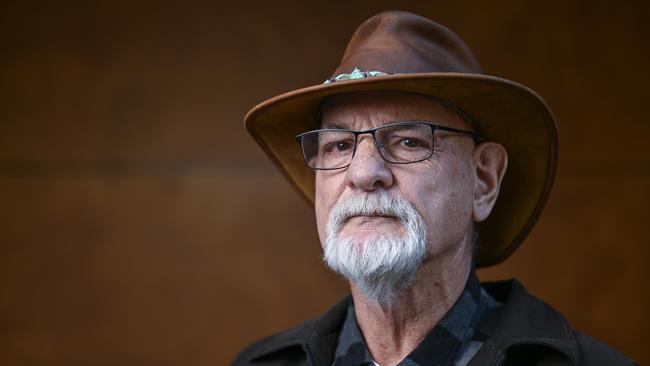

After more than 60 years, Peter Preneas still remembers how the catcalls echoed through the cramped dormitories of Mount Penang Training School for Boys.

They started when a fellow inmate was being violated. “When someone was being called out, you’d get catcalls going through the dorm – meow!” Preneas, 77, tells Inquirer.

“I was shit scared, so I stayed right away. You’d keep to yourself. You know what can happen, so you have to be very careful.”

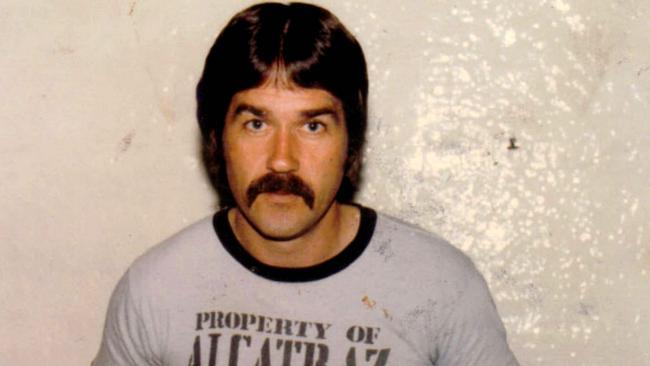

It was here, near Gosford, on the NSW central coast, that a young Stewart John Regan was incarcerated in the 1960s, chewed up and spat out as a fledgling criminal.

Regan’s short-lived criminal career and assassination in 1974 in a Marrickville backstreet is investigated in The Australian’s newest true-crime podcast, The Gangster’s Ghost.

Preneas was sent to Mount Penang on a general committal in the mid-60s after he repeatedly ran away from the home of his abusive, gambling-addicted father, who snatched him out of his mother’s arms on a train in Cairns in 1950. He was just 18 months old at the time and wouldn’t reunite with her until his mid-30s.

His father had a habit of packing up and moving his family every time one of his businesses went bust, including south to NSW.

Preneas endured years of physical and emotional abuse while in the custody of his father and stepmother, a cruel woman who called him “sakatevo” – Greek for “cripple” – after he contracted polio.

“I was pretty alone and a loner, so I kept running away,” he says. “They’d catch me, take me to court the next day, let me out that afternoon. I’d be gone the next day.”

He did stints at other juvenile institutions across NSW before landing at Mount Penang, where he was made a ward of the state because his father refused to grant permission for the surgeries he needed following complications from polio.

At the time it was touted by the Child Welfare Department of NSW as a model institution for rehabilitation, with living standards “no lower and sometimes higher than those in a first-class boarding school”. In reality it was rife with violent abuse perpetrated by authoritarians against their charges and boys against one another.

Many witnessed the horrendous treatment, others were physically assaulted and some were sexually assaulted. Boys who misbehaved at other institutions were threatened with transfers to Mount Penang, as it garnered a reputation among the state’s “delinquent” youth as a place to be avoided or escaped.

So Preneas ran from there, too. “I had a £1 note hidden in my crutches, in the handle, ready to go,” he said.

For his trouble, he was subjected to Penang’s unique brand of discipline. “The officers would get the kids to bash you up,” he recalls. “I can’t remember how many times I ended up on the ground being punched. Because I wouldn’t take it. I’d have a go.”

Preneas believes he escaped sexual abuse at Mount Penang because of his disability. But he, like thousands of others, has never really recovered.

By the end of the 50s, nearly 400 boys aged mostly between 14 and 16 resided at Mount Penang, despite its capacity for just 280. Estimates suggest 20 to 30 per cent of the boys were Indigenous, though it is thought the true number is much higher.

The campus was split into two accommodations: four dormitories housing about 80 boys and the Privilege Cottage, which later was renamed as McCabe Cottage.

A report from the 1987 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody said residing at McCabe Cottage was “the highest reward given for performance and which ran a very liberal, unstructured program with a minimum of staff supervision”.

It said the boys who resided in Privilege Cottage were known as “trustees” and tended to be placed there to dole out punishments on behalf of the officers, known as “screws”. The dorms were supervised by just one member of staff per eight-hour shift who enforced strict rules and allegedly enthusiastically punished anyone who broke them. Indiscretions were known as “bounces” and tracked through a demerits-type system that reset every day.

Speaking out of turn or looking at someone the wrong way could result in inmates being deprived of meals and privileges, kept in isolation or subjected to Dickensian physical and psychological abuse.

Doctor Wayne Applebee – who was at Mount Penang as a young man – recalled the practice of “holystoning” in his PhD thesis. “Holystoning is where a person squats on their knees with a piece of sandstone … and it entails moving the block from side to side across the wooden boards for up to three hours,” he wrote.

The holystone was presumably named for the gritty stone used by naval forces to scrub a ship’s decks – a nod to the campus’s shipbuilding roots. Applebee recounts being subjected to the holystone on his first day at Mount Penang after one of the institution’s gangs targeted him for refusing to give them his “grouse” – tobacco.

“I held my own for a time, but I was bashed and kicked by the three Store Boys and then ‘paraded’ for starting a fight,” Applebee wrote. “After that, I was physically tortured through … holystoning.”

He recounted how his bare knees started to bleed after just a few minutes. “It would be weeks before my knees healed; each night they would weep enough to cause the sheets to stick to them.”

A lack of medical attention and basic hygiene meant the wounds became routinely infected.

In a submission to the 2003 Royal Commission into Children in Institutional Care, Barry Stanley Meekings recalled being ordered to “water a paddock with a billy can and a teaspoon for punishment”. Other inmates have posted on social media about the “bull ring”, a circular concrete slab they were forced to scrub with a nail brush.

The incarcerated boys also were made to perform hard physical labour without exception.

“On my arrival, the company I was assigned to was cutting and breaking out sandstone using crowbars, picks, shovels, hammer and gads to break the stone free from the layers of rock,” Applebee tells Inquirer.

Preneas, who used crutches for the duration of his time at Mount Penang, recalls being roped into “crow shooting”, where boys were lined up left to right and handed shovels and mattocks to remove obstructions like trees and rocks.

A 1988-89 report of the death of Indigenous man Malcolm Smith – who had done two stints at Mount Penang and who died in the Malabar Assessment Unit at Long Bay jail in Sydney from self-inflicted wounds following a psychotic episode in 1982 – described Mount Penang as a “paramilitary institution” that was “based on very strict discipline and requirement of hard work”.

“It was a carefully constructed system that debased the inmates, forcing them to behave in such a way that for the slightest infractions,” Applebee says.

The reasons for Regan’s incarceration at Mount Penang are unclear but it’s thought he was sent there as punishment for a string of assaults. “The solidly built youth was well known for painting swastikas on cars and hitting the people who objected,” read one newspaper report following Regan’s death in 1974. “It was after one of these assaults that he made his first appearance in the Children’s Court and, thereafter, in the Gosford Boys Home and Mount Penang Training Centre.”

It’s possible Regan was removed from the care of his mother, Clare – a hard woman known as The Colonel – because she was believed to be running a handful of sex workers out of her Darlinghurst home.

The institution’s harsh treatment, hard labour and inadequate accommodation meant Mount Penang produced some of Australia’s most prolific criminals, including notorious standover man and murderer Neddy Smith, bookmaker George Freeman and Sydney underworld figure Ron Feeney.

After leaving Mount Penang, Regan quickly established himself as a drug dealer, pimp, standover man and murderer. Several of his contemporaries found themselves back there or locked up elsewhere, some more than once.

Bank robber Bernie Matthews – who was incarcerated at Mount Penang in the mid-60s – told The Australian’s senior reporter Matthew Condon in a new episode of The Gangster’s Ghost there was a boomerang over the front gate of the campus. “It was quite simple: you’re gonna come back,” he said. “That was the message you carry.”

But not Preneas. “I was angry. I said back then, ‘You’ll never lock me up again because I’ll kill you or you’ll kill me. It won’t happen.’ And it’s never happened.”

Lacking formal education, he found work renovating massage parlours for a friend in Sydney’s inner east after leaving Mount Penang. It was a job he enjoyed, though it meant crossing paths with underworld figures such as Lennie McPherson and Freeman.

“We knew them, we knew of their reputation, but we avoided them because we weren’t into drugs. They were all into drug dealing,” he says. “There was heroin everywhere – everywhere – back then.”

Preneas put his skills to work renovating his own home and later ran a successful security business for a time after marrying and having children.

To date, 10 people have been charged by the NSW Police Strike Force Eckersley, which was established in 2016 after a several complaints were made to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.

They include former superintendent Laurence “Laurie” Maher, who was accused of sexually abusing six boys at Mount Penang between 1977 and 1988.

People who were sexually abused at Mount Penang are eligible to apply for compensation through the National Redress Scheme, which started in mid-2018. The scheme is due to end in June 2028, and there are opportunities for those who apply for redress through the scheme to seek independent legal advice.

Hassan Ehsan SC of Turner Freeman Lawyers – who has represented more than 20 people in historic sexual abuse claims against Mount Penang – encourages them to do so before accepting an offer made by the Scheme, because survivors cannot legally pursue civil claims after settlement.

But is there compensation enough for the horror inflicted on generations of boys at Mount Penang? “Like I say to my clients: you can’t quantify a childhood,” Ehsan says. “So for them ‘success’ is a financial outcome … but it’s also more about the accountability, acknowledgment, and the apology that goes with it.”

Survivors can access 24/7 support through the National Redress Scheme.

Subscribers hear new episodes of The Gangster’s Ghost first. Listen now at gangstersghost.com.au.