The art of reporting, straight from Harry the Horse

Something precious was lost in the transformation of journalism from a trade to an elite profession.

More than half a century has passed since that day, that Monday morning, when I sat beside Harry the Horse at the reporters’ table inside a hall somewhere in Fitzroy and, panic stricken, I looked at Harry and Harry looked at me and whispered, “You write when I write.” I did as I was told. I watched Harry. He did not try to take down everything that was said. He had a big notebook and wrote what I later realised was perfect shorthand. He wrote only every now and then.

He was calm. I was panicked. When he wrote something down, he looked at me and winked and pointed at my notebook. I scribbled furiously. I could not write shorthand. I was three weeks into my cadetship. Shorthand classes had not yet begun. There was no way I should have been there covering the opening day of a major inquiry.

The chief of staff had sent me because everyone was certain the inquiry would be adjourned immediately to another date. Instead, it was straight into it. I think the inquiry went for six weeks and involved a notorious Melbourne juvenile detention centre, the name of which I cannot recall.

I remember Harry the Horse and his kindness. “Write when I write.” I did, for weeks, though as the weeks passed I think I got the hang of it and could concentrate less on what Harry was doing.

That’s not all I remember about Harry. I remember how every day at the lunch break, Harry and I walked briskly to the pub, which was perhaps 300m away. We would stand at the bar and Harry would have four pots of beer. Over the weeks reporting the inquiry, I made the progression from a one-pot lunch to two. Over the weeks, Harry taught me a lot about reporting – including the role of alcohol in a reporter’s life. He taught me how to listen and take notes at the same time. He taught me to listen for the story.

Harry the Horse was a giant of a man, red-faced and red-nosed as I remember him, but perhaps that’s just a Damon Runyonesque flourish that has somehow sneaked its way into my memory of Harry. Harry the Horse. Can you imagine an ABC reporter in 2024 nicknamed Harry the Horse because he is so large, and can drink a proverbial horse under the table?

‘Journalism was once a trade; reporters at best had a high school education. They were trained on the job, like most trade apprentices.’

I remembered Harry – you know I cannot remember whether he was actually a Harry – when I was reading an article in Persuasion, a site on the Substack platform that its founder, prominent American political scientist Yascha Mounk, describes as committed to free speech and open and free debate about ideas. Some of its contributors are worth reading.

You may well ask how it was that I thought of Harry the Horse when I was reading a piece about journalism written by a guy called William Deresiewicz, who is a self-described author, literary critic and essayist and a former academic who taught English literature at Yale, one of America’s elite universities. No Harry the Horse he.

I can’t even imagine Harry reading it past the first paragraph, which is too long. The anecdote – a professor of journalism at Columbia made fun of the student Deresiewicz when he used the phrase “bodes well” – is rather lame. Harry would have made fun of him, too. Rightfully so.

Yet Deresiewicz has written a piece about journalism that brought back memories of Harry the Horse and of the reporters like him, men mostly, I worked with and learnt from when I was young and raw and in love with being a reporter. He has written a piece about how journalism was once a trade; reporters at best had a high school education. They were trained on the job, like most trade apprentices.

They were working-class men – there were a few women, but only a few. They were anti-intellectual, suspicious of ideas and didn’t like big words. They loathed pretentiousness. Especially the pretentiousness of academic experts who spoke in a language that came from a place these reporters did not know and had never visited.

Deresiewicz imagines what the working-class life was like, how it formed these working-class journalists. Some of what he has to say is eloquent and true, and some of it is the imaginings of a highly educated member of an elite that is as far away from working-class people and the old working-class journalists as it is possible to be.

“Your parents work with their hands, with things or on intimate, sometimes bodily terms with other people. Your environment is raw and rough – asphalt, plain talk, stains and smells – not cushioned and sweetened. You imbibe a respect for concrete, the tangible, that what can be known through direct experience and a corresponding contempt for euphemism and cant.”

The world, for these reporters, was chaotic and full of paradox. The reporters were imbued with a sense of wonder and curiosity about the world. Their job was not to make sense of the world but to report it; what they saw and heard, and the lives people were living. Not ideas about their lives but the details of their lives – where they worked and played and how they aged and even how they died.

“At the source of their moral commitments, they had not rules but instincts, a feeling for the difference between right and wrong. For the masses, they felt not pity but solidarity, since they were of them.”

Then at some indeterminate time journalism became a profession. Newspapers started to hire university graduates as trainees. In 1970 when I started at The Age, out of 12 trainees, two were graduates. The stars of my year, household names now, came to The Age after school. By the time The Age was hiring trainees when I was editor in the late 1990s, the days when a high school student could get a traineeship with any mainstream media company were long gone. Hundreds – perhaps even thousands – of young graduates were competing for traineeships. Many of them were academically brilliant and many of them, it is true, had gone to private schools.

By then there were few editors and television and radio executive producers left who had gone straight into a traineeship program at a newspaper or at the ABC fresh out of school.

Graduates, graduates everywhere. Some are the graduates of university journalism courses that have thousands of students and have been set up at virtually every university in Australia. Some are law graduates and even graduates in medicine, formidably trained and formidably ambitious.

Journalism has become a profession, an elite profession at that. Deresiewicz refers to a recent study of the background of journalists at The New York Times that showed more than 50 per cent of them went to an elite American university. Perhaps the percentage of elite university-trained journalists would not be as high at some other media companies but perhaps not. The competition for jobs in an ever-shrinking profession is intense in the US and it is intense in Australia. Only the “best” are hired.

Journalists are invariably the sons and daughters of the middle class or even the upper middle class. They have little or no contact with working-class people. At university, they learn to see the world as abstractions and ideas and from the point of view of experts and to speak the language of experts.

And the experts from whom they learn are uniformly from the left and uniformly teach the new dogmas of the academic left that may include critical race theory, intersectionality and post-colonialism. What this means, according to Deresiewicz, is that journalism has become a captive of a sort of pseudo-intellectualism in which there is no truth and no concrete world to be discovered and reported. Theirs is a world of expert opinion and ideological abstractions.

Perhaps Deresiewicz is overstating the capture of journalism by the proponents of the new academic dogmas. There are still journalists – many who don’t work in the great liberal media institutions such as The New York Times, though some do – who are not social justice warriors. And perhaps he is overstating how far away many journalists have moved from what journalists were when I first started in the trade – it was still a trade back then – a fair time ago: they were reporters. And in the 1970s and even into the ’80s they were in a poorly paid trade. Printers earnt more. Teachers earnt more.

They have moved far away from reporters like Harry the Horse and the reporters I worked with at The Sun News-Pictorial, where I went to work after I had started at The Age. I loved the Sun. I learnt to be a reporter and to love reporting and I learnt to write clearly and accessibly, without using cliches if possible, in short sentences if possible.

I learnt a lot from those difficult buggers, some of them bad husbands, some of them drunk a lot of the time, especially around 7pm when they were on their break―– we worked 2pm to 11pm shifts and they could be found at the pub across the road from the office seriously drinking for an hour or so and perhaps they would demolish a leathery steak and chips or a bowl of fried dim sims before they made their way back to the office to write their stories.

Some of the best of them fell down the stairs quite regularly on their way back to the office. By the best I mean those who went out every afternoon in search of a story or who worked the morning shift covering the magistrates’ courts and who came back and went to the pub and drank a fair bit and then wrote their stories with a clarity and simplicity and a lovely rhythm to their sentences that was just a wonder to behold. And each morning, more than a million Victorians read their stories, yet these reporters were never celebrities, never thought of themselves as anything but a bunch of outsiders, not much loved by the powerful, to say the least, out there in the chaos of the world in search of a story they could write, and write it in a way that would grab the attention of readers of the paper.

Life stories they were. Stories of the streets and the courts and the police stations and the schools and stories about sporting heroes and villains. They made some sort of order out of chaos.

I should not mythologise them too much. They were not angels. Some of them were bad drunks and I am not all that upset that one consequence of the middle-class, university-educated takeover of journalism has been an end more or less to the drinking culture that in many ways blighted the lives of many of the reporters I knew when I was young. Some of them died young, in their 40s or early 50s.

But something vital has been lost by the transformation of journalism into a profession with its stars and celebrities and university-trained “thinkers” and journalists who are traffickers in ideas and ideological dogmas. And now we have journalists who are activists for good causes, imbued, most of them, with ideological zeal. They draft group letters designed to “educate” journalists and they spend a lot of time pondering the meaning of truth and how to advance the cause of social justice or trans rights or anti-colonialism.

But most of them have no real interest, it seems to me, in being what Harry the Horse was and what those mentors of mine at the Sun News-Pictorial were: reporters. They are not reporters. They do not describe themselves as reporters. They are journalists. They are commentators. They are editors who don’t, in some cases, actually edit anything. They know little, many of them, about the city in which they live. Many have never been inside a courtroom. A police station. A hospital emergency room. Many have never been to the outer suburbs of their cities where people about whom they know nothing except for cliches live and work and grow old.

I do not know whether Harry the Horse is still alive. Most of the reporters I worked with at the Sun are dead, the ones I considered particularly gifted. But I fear that something precious died when journalism became a profession. What was lost was a way of understanding and making sense of the world by taking with you a notebook and a pen and going out in search of a good story.

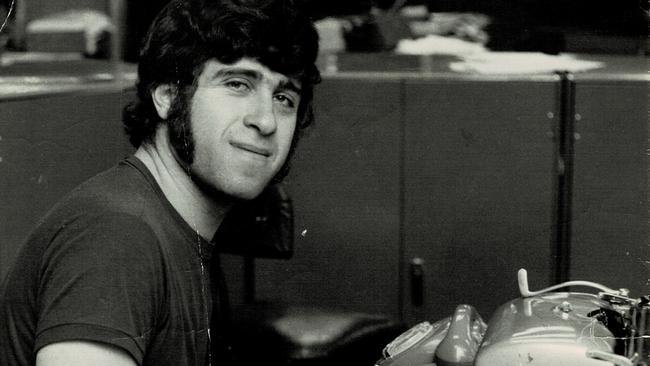

Michael Gawenda is a former editor of The Age and is the author of the book My Life as a Jew.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout