The A to Xi of Trump’s tariffs – what a global trade war might mean

The world is holding its breath to see how far the US President will go in his mission to level a playing field that has been skewed by a deeply mercantilist China

Donald Trump campaigned as the Tariff Man. All indications are that as president he intends to deliver on his promise to introduce sweeping tariffs on imports into the US.

Trump has announced plans to levy duties on China, Canada and Mexico, and he signed an executive order on the first day of his new administration directing officials to conduct a thorough review of US trade policy. Another review will examine the US industrial and manufacturing base to assess whether further national security tariffs are warranted.

When his political epitaph is written, will Trump be remembered as the US president who initiated a trade war, caused a global recession and destroyed the last vestiges of a waning international order crafted and policed by his 13 post-World War II predecessors? Or are his threats to impose punitive tariffs a justifiable attempt to level the playing field of an unfair international trading system gamed by a mercantilist China?

For an open trading nation such as Australia, the stakes couldn’t be higher. Regardless of his motives, Trump’s tariff play threatens to up-end the international trading system, destabilise markets, risk retaliation and pose serious problems for the Australian economy should China be the chief target. In a worse-case scenario, a trade war could trigger military conflict, as French economist Emmanuel Martin reminds us.

At first glance, Trump’s much publicised tariffs seem more like a wrecking ball than an astutely conceived policy designed to restore America’s economic primacy and break China’s stranglehold on global supply chains. He has threatened a universal tariff of up to 20 per cent on all imports into the US; an initial 10 per cent tariff rising to 60 per cent on China; a 10 per cent tariff and up to 25 per cent on imports from neighbouring Canada and Mexico; a 100 per cent tariff on BRICS countries Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (plus five other members) if they try to replace the US dollar as the main global currency; a 25 per cent tariff on the European Union unless the EU buys more oil and liquid natural gas from the US; “high levels of taxes, tariffs and sanctions” on Russia if President Vladimir Putin doesn’t settle his conflict with Ukraine “soon”; and a 25 per cent tariff on Colombia, later retracted but kept in reserve after Bogota agreed to allow the US to repatriate undocumented Colombian migrants.

But there is little doubt that China is the chief target. The Communist Party state is the only peer competitor to the US and the focus of Trump’s longstanding grievance that Beijing is responsible for “ripping off” the US using unfair trade practices, a view widely shared by Americans.

The big problem for the US and the world is that so much is made in China now – one third of global apparel exports, 30 per cent of global electronics, more than 50 per cent of passenger cars and 80 per cent of solar power modules. But Beijing wants more.

The UN estimates that by 2030 China will command 45 per cent of all manufacturing, a level of dominance seen only twice before – by the US in the early years after World War II and the UK at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. This has generated a $US1 trillion surplus for China but created a dangerous global trade imbalance.

“Tariffing the bejesus out of China won’t solve this problem,” says former US Treasury official Brad Setser. In 2018, Trump applied duties of 25 per cent on $US34bn of Chinese imports. Beijing responded with countervailing tariffs of equal size and scope on US imports before both sides pulled back and negotiated a deal. Trump characteristically declared victory. But this was only the opening salvo in a trade war that is set to worsen if he goes ahead with his threat to levy a 60 per cent tariff on all imports from China.

The problem with trade wars is that there are seldom any winners. Most economists agree that Trump’s tariffs are self-defeating because the costs will be borne by American importers who will inevitably pass them on to consumers, driving up prices and fuelling inflation. Since this is obviously counter-productive, it begs the question of whether Trump’s tariff threats are primarily a negotiating strategy to achieve political and strategic goals rather than levelling the trade playing field.

The answer is that Trump thinks tariffs can do both. He has specifically linked his tariffs to non-economic goals declaring that the reason for imposing tariffs on Mexico and Canada, the two largest export markets for American goods, is the “thousands of people” entering from both countries and bringing with them “crime and drugs never seen before”. He promises these tariffs “will remain in effect until such time as drugs, in particular fentanyl, and all illegal aliens stop the invasion of our country”.

Trump is not the first world leader or US president to engage in power trading for geopolitical ends or to force market access. Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II was a power trader, as was Adolf Hitler. President Ronald Reagan forced Japan to dismantle protectionist barriers by imposing a wide range of trade restrictions using tariffs and quotas on politically sensitive Japanese export industries like cars and motorcycles. Remember the graphic images of American autoworkers smashing Toyota cars in protest at “cheap” Japanese cars allegedly undercutting those produced in the US.

The use of tariffs and other forms of trade discrimination for geopolitical purposes – what Walter Russell Mead calls the “Trumpification of world politics” – is fast becoming a tool of first resort in the national strategies of the larger economies. As Australians know only too well, China has repeatedly used its trade and economic clout to punish or pressure other countries into compliance, so it would be wrong to single out Trump for weaponising trade.

It would also be wrong to think that Trump is bluffing, or that he isn’t deeply committed to righting what he considers to be a flawed and unjust trading system. It’s true that Trump’s bark is often worse than his bite and he has a habit of reversing policy positions and not following through on his threats. But his use of tariffs and trade pressure is likely to be a defining feature of his presidency because they play to America’s economic strengths and appeal to Trump’s persona, deal-making instincts and nationalist-populist agenda.

Trump has categorically refuted a recent Washington Post article suggesting that his tariffs would only be applied to sectors deemed critical to national and economic security, branding the report as “fake news” and “incorrectly stating that my tariff policy will be pared back”. He has never disguised his visceral disregard for the World Trade Organisation, believing it has been captured by China. He has repeatedly threatened to leave the WTO, complaining that it has been “screwing us for years” and is the single worse trade deal ever made. He believes that China is waging economic war against America and the US must fight fire with fire. And he is scathing of allies who outsource their security to the US.

Stephen Miran, Trump’s nominee for chair of his Council of Economic Advisers, argues that to deter retaliation from nominal friends the US could “declare that it views joint defence obligations and the American defence umbrella as less binding or reliable for nations which implement retaliatory tariffs”, a shot across the bow of fellow NATO members and non-NATO Asian allies such as Japan and South Korea. If Trump were to take this advice the whole US alliance system could unravel.

Miran has another unorthodox view that should ring alarm bells – that the US could be better off with average tariffs of about 20 per cent and as high as 50 per cent rather than the current 2 per cent. This, says Miran, would fundamentally restructure the global economic and financial system and under optimal conditions favour the US.

The difficulty of assessing the impact of Trump’s tariffs is that the devil is in the detail. We still don’t know how they will be implemented or how other countries will respond. His advisers are split between gradualists who want to ramp up tariffs slowly and those who favour a big bang approach. Among the gradualists is Trump’s pick for Treasury secretary, Scott Bessent. The former hedge fund manager won’t want to destabilise markets by the sudden imposition of massive tariffs. But other influential voices such as Miran, long-time trade adviser Peter Navarro and likely commerce secretary Howard Lutnick are tariff hawks.

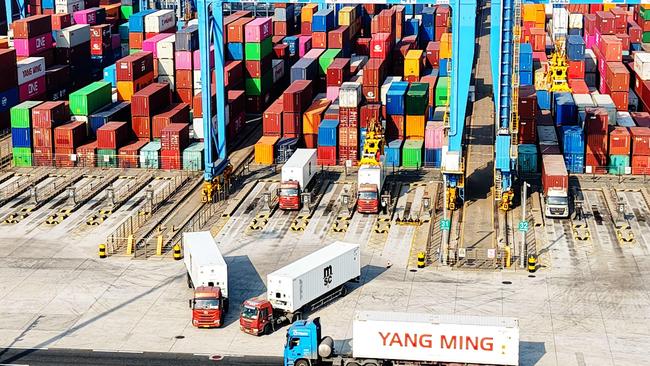

American economist Betsey Stevenson doubts that Trump will go through with his tariffs given their inflationary impact. “Trump will not do big tariffs, but he definitely will say that he did. Whatever policy passes will have loopholes big enough to push a container ship or a huge fresh vegetable truck from Mexico through,” she posted on social media platform X. Most economists think that Trump’s tariffs will be modest not extreme.

Trump will not do big tariffs, but he definitely will say that he did. Whatever policy passes will have loop holes big enough to push a container ship or a huge fresh vegetable truck from Mexico through.

— Betsey Stevenson (@BetseyStevenson) November 26, 2024

What’s certain is that other countries will retaliate strongly if backed into a corner. This could force Trump to reconsider the scope and duration of his tariffs, particularly if he feels key constituencies like the automobile sector, farm lobby and big tech will be negatively impacted. Canada and Mexico have made it abundantly clear that if the US slaps them with 25 per cent tariffs they will reciprocate. As America’s two largest trading partners, this could really hurt the US economy. Canada and Mexico are central to US vehicle supply chains providing $US100bn in auto parts. Last year about 10 per cent of vehicles sold in the US were built in Mexico and 7 per cent were imported from Canada. Japan and South Korea, two US allies with world-leading car industries, could join Canada and Mexico in taking retaliatory action if they are hit with tariffs.

Running a trade surplus with the US of $US33bn, European countries are particularly vulnerable to US tariffs because of their ailing economies and weak political leadership. The EU will come under real pressure to buy more US oil and gas to avoid tariffs, which could send Europe into recession. “I told the European Union that they must make up their tremendous deficit with the United States by the large-scale purchase of our oil and gas. Otherwise it is TARIFF’S all the way !!!” Trump wrote on his Truth Social media site in December.

If EU concessions don’t eventuate, or Trump is not satisfied, EU retaliation is inevitable which could pitch the world’s largest and second-largest economies into a full-blown trade war. In 2018, the EU threatened to target US exports including Harley-Davidson bikes, Levi’s jeans and Kentucky bourbon if the US pushed ahead with punitive tariffs on foreign steel. A settlement was reached when EU Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker, agreed to buy billions of dollars of US exports, including natural gas.

But China’s response matters most as the third-largest economy and the key to determining whether the world can navigate Trump’s protectionist onslaught without dangerously destabilising international trade. It’s unlikely that his administration would be foolish enough to unite friends and adversaries in a coalition of the coerced against the US, although the law of unintended consequences means such a scenario cannot be ruled out. The smart play would be to extract concessions from friendly states, claim victory and then concentrate fire on China. This seems to be where Trump is headed. Interviewed in The Wall Street Journal, senator Tom Cotton, a close ally, thinks Trump will take a harder line with China, which he called a “horse of a different colour” because of the economic and national security threat the communist nation poses to the US.

Beijing has spent many months preparing for Trump’s tariffs, having learned valuable lessons from the first trade stoush. In the red corner of this looming championship bout, team leader Xi Jinping knows China must play defence as well as offence to have any chance of beating team USA. Xi will attempt to avoid Trump’s tariffs through backdoor methods such as redirecting US-bound goods made in China through third countries in Asia and Latin America, a tactic that has already proved successful. One reason Trump is looking at a universal tariff is to block China from doing this.

Offensively, Xi knows he can’t win a straight tit-for-tat tariff contest because the US buys roughly three times more from China than China buys from the US. So Xi will pursue a three-pronged approach – concede enough to mollify Trump without damaging the slowing Chinese economy; seize the moral high ground by positioning his country as the defender of the multilateral trading system against a protectionist America; and look for unique points of leverage as he did in 2018 when he targeted the farming states that propelled Trump to victory with punitive tariffs of his own on US agricultural exports, notably sorghum, corn, pork and soybeans.

This time Xi’s trump card and weapon of choice will be critical minerals because China is the largest supplier of 26 of the 50 minerals classified by the US government as critical to the economy. Think wind turbines, mobile phones, computers, semiconductors and advanced defence systems. China responded to the Biden administration’s tech restrictions by banning exports of gallium, germanium and antimony, disrupting the markets for all three metals and forcing the US to look elsewhere.

Despite the many uncertainties surrounding the timing and scope of Trump’s tariffs, three broad conclusions can be drawn about their impact. First, the short-term inflationary and geopolitical impact of tariffs should be manageable without major disturbances to the international economy. But if they are prolonged and tariffs become a structural feature of international trade, the consequences will be more serious. A tariff war will weaken the international trading system and the WTO, taking the world further down the path towards a power-based trading system where the strong do what they want and the weak suffer. Smaller economies will be forced to cut unfavourable deals with the big players. This would be unequivocally bad for multilateral trade, the health of the global economy and trade-dependent countries like Australia.

Second, often forgotten in conventional analyses of trade disputes is that the international trading system established by the US and other Western nations was also about alliance management as well as institutionalised commitments to free trade. Trade tensions between the US and Europe could fragment NATO and adversely impact on the US alliance system in Asia should its members come to believe that US agreements aren’t worth the paper they are written on.

Third, wielding a big tariff stick to achieve trade and political “wins” will encourage retaliatory and imitative behaviour. Xi can inflict pain on the US with his own tariffs and trade restrictions. But he must be careful to use them sparingly to avoid the risk of overreach and damaging his own economy, as must Trump.

The question is who can last the longest and has the most weapons at his disposal? Trump is banking on it being the US, which is still the world’s greatest economic and financial power. He may be right.

Alan Dupont is chief executive of geopolitical consultancy The Cognoscenti Group and a non-resident fellow at the Lowy Institute.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout