Test for Albanese government to make digital giants comply with Australian law

Traditional media is regulated for sound reasons; more effort is needed to calmly explain why there’s no logical basis for exempting certain material on the internet.

How should the Australian government regulate global businesses such as Facebook (owned by Meta), Google (owned by Alphabet), X (formerly Twitter) and TikTok, and the content these businesses make available to Australians on their platforms?

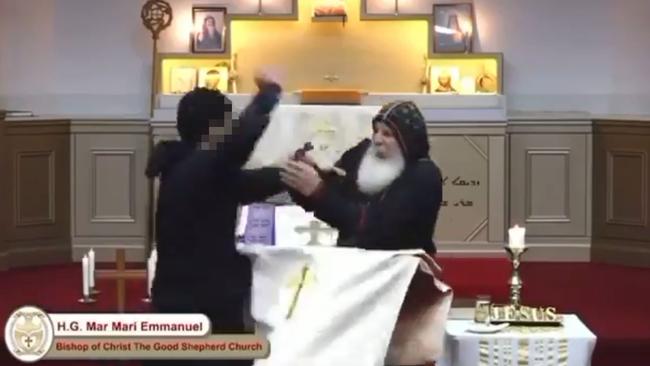

This question has prompted intense public debate in the past couple of weeks since the shocking knife attack at Christ the Good Shepherd Church in western Sydney, and a video of that violent attack being circulated online.

Australia’s eSafety commissioner, Julie Inman Grant, has directed several social media platforms to block access to this video in Australia – and while most have complied, X has resisted and its owner, Elon Musk, has vigorously criticised the direction being made.

These are not new issues. The appalling Christchurch mosque attack in March 2019, with the murders of more than 50 people livestreamed on Facebook, prompted similar public debate. In fact, the question of how to regulate the internet has challenged governments since internet use became widespread in the 1990s.

The question was made only harder when Apple launched the iPhone in 2007, creating a new category of device, the smartphone. Before too long most people were carrying a device that, among other things, let them take photos and videos, and send them instantaneously to all the people they knew and many more they did not.

All of this creates considerable challenges for a government that wants to regulate the content its citizens can read, see or hear.

Some respond by saying that such regulation is wholly undesirable and it is a good thing that it is now much harder. But it does not take much thought to see that there are sound reasons governments have always placed some limits on the content their citizens can read in books or newspapers, listen to on radio or see on television or at the cinema.

There are prohibitions on broadcasting material that is extremely violent or sexually explicit, on the grounds that it offends public standards of decency or it exposes children to material that is age-inappropriate or that it will surprise and disturb people who were not expecting such material. There are restrictions on publishing unfounded criticisms of others, through the operation of defamation law.

If you print or broadcast a work without the agreement of the person who holds the intellectual property rights to that work – for example, its author – you can be sued and made to pay a lot of money to the rights owner. There are laws restricting content that instructs people in how to make a chemical weapon or a nuclear bomb or that reveals secrets that could endanger national security.

There are many good public policy grounds, then, on which some limits are imposed on the content that can be distributed over television or radio or through newspapers. Once that is accepted, there is no logical basis for not imposing analogous limits when it comes to material made available over the internet.

It is certainly true that enforcing such laws is more complicated in an online world where just about anybody can make a statement or release an image that potentially can reach billions of people.

Traditionally, in regulating content, governments dealt with a small number of organisations that were well resourced, incentivised to behave lawfully and operated entirely within their own borders – essentially, media organisations.

Today, by contrast, content can be posted to the internet by anybody, anywhere; it is then visible to potentially billions of people. And unlike traditional media organisations, online media platforms do not commission, curate or check the content on their platforms, at least not in any remotely satisfactory way.

But there is no doubt the internet businesses have taken advantage of these factors to argue that, as a matter of principle, they should not have to face the kind of content regulation that have long applied in film, television, radio and newspapers. It is remarkable that their position was accepted by courts and governments around the world for so long.

Imagine if I owned 200 billboards in prominent sites around Sydney, and I invited people to submit to me images that were violent or sexually explicit or text that made nasty and factually incorrect claims about other people that I would put up on those billboards. If, when people complained, I responded, “I am not responsible – my business model does not include vetting what is put up on the billboards”, there would be outrage. Yet this is effectively what the global digital platforms such as Facebook, Google and X have said.

There are several reasons the internet giants got away with this position for so long. One is that it all happened so fast. In 30 years the internet has gone from being a specialised resource used by a small number of scientists and researchers to being a mass-market consumer phenomenon, with five billion people online around the world. It is not surprising governments have taken a little while to respond.

Another reason is the highly decentralised nature of the internet. It is not located or controlled in any one place. Rather, it is a collection of billions of computers – from massive supercomputers in academic and research institutions to computers in millions of businesses, schools and other organisations around the world, to the smartphones billions of people across our planet now carry.

As a result it is not always obvious which government should take the lead in regulating when, for example, highly violent content is stored on a server in one country and seen by viewers in another country. But while these were novel issues 30 years ago, they are much better understood today – and very much more the subject of regulatory focus and intergovernmental co-operation.

Third, there is the quite influential idea, in the early years of the internet, that the internet should exist beyond the sovereignty of nation-states.

In 1996, US cyberlibertarian and poet John Perry Barlow issued his Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, which begins: “Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.”

The idea of an internet beyond the reach of government might have been tenable while it was a specialised resource used by a small number of researchers and academics. But it was increasingly difficult to sustain once the internet became a mass-market consumer phenomenon.

When people interact in the physical town square, they take it for granted the rule of law applies. If they are assaulted, or defrauded, or otherwise harmed, they can go to the police and seek assistance, or they can go to court and seek redress. As the internet took hold, it quickly became apparent people expected the same thing when they interacted in the digital town square.

Another factor that slowed the introduction of regulation was the concern that it would be a threat to free speech. We have seen this again in recent days, with Musk calling the eSafety Commissioner’s action an attack on free speech.

Such an argument influenced the light-touch regulatory framework for internet businesses adopted in the US (where of course there are strong free speech protections under the first amendment to the constitution.) But even in the US there are limits on free speech: in the famous formulation of one Supreme Court judge, no one is free to shout “Fire!” in a crowded theatre.

And even in the US (and certainly in Australia and most other nations), the desirability of protecting free speech has not prevented the establishment of classification systems that regulate the nature of extremely violent or sexually explicit content that can be seen on television, at the cinema or in a newspaper or magazine. In short, the idea that internet-based businesses should be free of such regulation – when every other content business is subject to it – is now treated much more sceptically than 30 years ago.

Governments, perhaps, can be forgiven for taking some time to work out how best to regulate the new online world. But, as time has passed, they have shown increasing confidence in their efforts and ability to regulate online activity. That has been the pattern in Australia and in many other nations.

The early approach was certainly quite diffident. In 1999, the Broadcasting Services Act was amended with the addition of a scheme to regulate online content in Australia. It provided for differential treatment of content hosted in Australia and content hosted overseas, with no capacity for the regulator to take firm action against the latter. This was based on the view at the time that attempting to impose Australian law on websites hosted overseas was a futile exercise.

Across time that view changed. For example, in 2013 Australia chaired the discussions that led to the UN General Assembly agreeing for the first time that the law applies online as it does offline.

At the same time, Australia took a world-leading position in establishing a domestic regulatory framework for dealing with particular kinds of objectionable online content – starting with cyberbullying content directed at children. In 2015, the Coalition government established the world’s first eSafety Commissioner and gave it statutory powers to deal with such content.

In 2017 we expanded the office to support all Australians and gave it new powers. In 2018 we added laws dealing with the unauthorised sharing of intimate images; in 2019 laws dealing with “abhorrent violent material”; and in 2021 we introduced a new Online Safety Act that expanded the powers of the eSafety Commissioner following extensive consultation.

The new Online Safety Act adopted some of the content regulation provisions from the 1999 act, but there are important differences. It gives those powers to the eSafety Commissioner (instead of the Australian Communications and Media Authority) and it gives the commissioner much stronger enforcement powers than the 1999 act.

No longer does it meekly assume that if the material is hosted on foreign servers the Australian government will not seek to exercise power; rather, it looks at the question of whether the content can be seen by Australians.

Australia also took a world-leading position on dealing with the market power of the global internet giants.

In 2020 the Morrison government announced we would legislate a news media bargaining code to regulate the commercial relationship between global digital giants Google and Facebook on the one hand, and Australian news media businesses such as Nine Entertainment and News Corp on the other hand.

We saw this as a competition policy problem – the global giants were using content produced and paid for by Australian news media businesses but refusing to pay for it, and they could do this only because of their market power.

But we also saw it as a media policy problem because it was leading to reduced advertising revenue for news media businesses, leading to a weaker, less diverse and less well-resourced media sector. In turn, we saw it as a problem for our liberal democracy, given the critical role played by the media. Facebook and Google strongly resisted this proposed legislation. Google threatened to shut down its search services in Australia. Facebook, notoriously, in February 2021, shut down the pages of numerous Australian news media businesses. It was crudely done, with the Facebook pages of hospitals, emergency services and even a rape crisis centre also being shut down.

These steps were taken in an attempt to intimidate the Australian government into backing down. They did not succeed. Once Australia’s News Media Bargaining Code was passed into law in early 2021, it worked. It brought the two global digital giants to the negotiating table with Australian news media businesses when many other governments around the world had tried and failed.

This was not the first time there had been such aggressive tactics used by big foreign technology businesses.

In 2018, the Australian government changed the law to remove an exemption from the GST that had previously applied to online transactions with a value below $1000. We did this because the exemption gave global internet businesses an unfair advantage over Australian businesses that were their competitors.

Amazon, the global ecommerce giant, protested strongly and withdrew services from Australia for about six months. But it subsequently chose to re-enter the market and comply with the new law regarding GST.

There was similar resistance from the global digital giants in 2014, when we were first working to establish the eSafety commissioner. The peak body for companies including Google, Facebook and Microsoft opposed our plans, saying in a submission that they had “serious practical concerns” and it was likely “the laws will be unable to keep pace with technological change”. This was a variant of an argument quite often deployed by such companies: if you pass this law Australia will become a technological backwater.

Musk’s recent bellicose response, then, is very much in the tradition of what we have seen from other big foreign technology businesses during the past few years. The previous Coalition government did not blink in the face of such responses; it is to be hoped the Albanese government shows similar resolve.

These are not new issues; indeed, they are issues the previous government considered very carefully as we developed the Online Safety Act, which was legislated in 2021. The steps the eSafety Commissioner has taken in the past week or so are to exercise powers given to her in that act.

Based on the playbook we have repeatedly seen big US digital companies use, there are likely quite a few steps yet to come in the handling of this issue. As with Facebook’s recent statement that it would not be renewing its deals with publishers under the News Media Bargaining Code, this presents a test for the Albanese government.

To date the response to X from Anthony Albanese and his ministers has largely been bluster. It is a shame we have not seen more effort to calmly explain why Australia has a regulatory framework for online content; how that framework has been developed across 25 years; why that framework carefully balances up the importance of free speech; and why there are sound public policy reasons to regulate the nature and extent of content that Australians can access, be that through traditional media or on the internet.

The previous Coalition government showed that with methodical policy work and with political will, the global digital giants can be made to comply with Australian law in the way they operate in this country. Our national reputation as a country that is among the more effective global regulators of the internet has been hard won; it will be a great shame if that reputation is damaged in the way the Albanese government handles these issues.

Paul Fletcher is the former communications minister and author of the 2021 book Governing in the Internet Age, on which this article is partly based.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout