Telling reasons behind Xi’s U-turn on dialogue

China is talking up perceived threats to its security while pursuing development abroad.

The world, as portrayed by Xi Jinping, is a scary place. It has entered “a new period of turbulence and change … The hegemonic, high-handed and bullying acts of using strength to intimidate the weak, taking from others by force and subterfuge, and playing zero-sum games are exerting grave harm”.

Xi also warned his 97 million Communist comrades in his work report to last month’s 20th party congress that “external efforts to suppress and contain China may escalate at any time … (as may) various black swan and grey rhino events … The world has once again reached a crossroads in history.”

Thus Xi’s sudden burst of global summiteering, including with Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, after 2½ years of staying at home as the people’s leader commanding the people’s war against Covid, is intended to strike his crucial domestic audience as brave, daring and decisive.

Immediately before the party congress, and after its program was bedded down, he flew to Kazakhstan, then to Uzbekistan for a Shanghai Co-operation Organisation summit, and a meeting with the leader he has called “my best, most intimate friend” – Russia’s now-pariah Vladimir Putin.

This week Xi has of course been in Bali for the G20 summit, and at the APEC summit in Bangkok.

After setting off such alarm bells at the party congress, Xi delivered his prescription for calming the anxieties of his fellow countrymen and women: more of the same, especially more of him. He will indeed continue as party general secretary and thus leader of China for another five years, and almost certainly an additional term after that, taking him to 2032, at least.

Our course within China is now, at last, correct, he has indicated. But we are surrounded by troublemakers orchestrated by Washington.

This marks a shift in locating the party’s core legitimacy. Previously, through the four increasingly prosperous post-Mao Zedong decades, support for continuing communist rule derived chiefly from economic opportunity.

But now, as the economy is fast fading towards a Japan-style flatlining, the party is seeking to base its legitimacy more in the international realm – in demonstrably safeguarding the country from hostile forces, and in expanding its benevolent influence such as through Xi’s new Global Development and Global Security Initiatives.

An official report noted that in choosing the party’s new leadership team, assessments were made according to “whether they were brave and good at fighting against the US and Western sanctions and safeguarding national security.”

The new head of China’s international relations – “diplomacy with Chinese characteristics,” which some are dubbing Xiplomacy – is Wang Yi, appointed to the Politburo aged 69. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ party secretary Qi Yu, widely credited with driving the diplomats’ “fighting spirit,” has been appointed to the party’s central committee, as has US ambassador Qin Gang, formerly Xi’s protocol chief, who is expected to become new Foreign Minister. Liu Jianchao, who like Qin Gang was also a government spokesman well known to foreign journalists, now heads the party’s increasingly powerful International Liaison department.

Since the congress, Xi has sought to double down on China’s surge towards global power. This has long been a Communist Party modus operandi – pushing swiftly after important meetings have consolidated its domestic grip, to make the wider world safe for itself.

But it now comprises an almost existential mission as the party seeks, in Xi’s work report words, “to ensure security in the pursuit of development.” Global and national goals are integrated in a new way: “Today our world, our times, and history are changing in ways like never before.”

Thus the need to “accelerate the development of China’s discourse and narrative systems, to better tell China’s stories, make China’s voice heard,” and to become even more “actively involved in setting global security rules,” in reforming the “global governance system.”

The leaders of Germany, Vietnam, Pakistan and Tanzania rushed to Beijing to greet Xi immediately after the congress – showing, said Global Times, that “more and more countries are optimistic about China’s future development”. This rush also revealed which countries and leaders seem most anxious about their own futures, and most eager to solicit special favours from Beijing.

Xi told German Chancellor Olaf Scholz that their nations should unite for peace in a “chaotic” world. Tanzania’s President Samia Suluhu Hassan gained somewhat more practical outcomes, signing 15 agreements in Beijing.

Tanzania is the locus of the first China-style party school in Africa, built with $US40m from the Communist Party, and 120 cadres from six parties that have ruled their African countries continuously since independence, have recently participated in the first training module there, led by the CCP’s International Liaison Department.

The Hong Kong leadership appointed by Beijing this year excitedly hosted a fortnight ago a Global Financial Leaders’ Investment Summit where such leaders queued to praise the alleged great re-emerging opportunities to get rich in and from Hong Kong and Beijing. The UBS chairman Colm Kelleher pledged: “We’re all very pro-China.” It was no surprise that optimistic investment bank forecasts about the lifting of Zero-Covid constraints early next year prompted a swift stock market uptick.

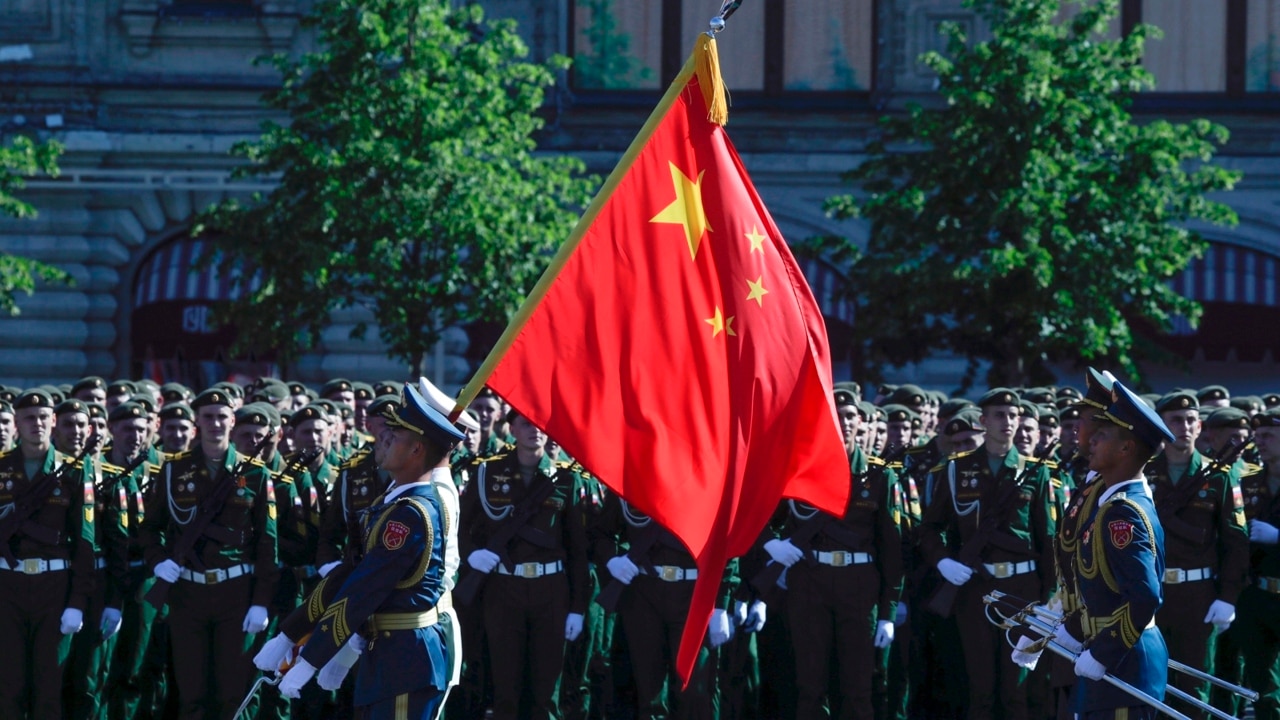

Despite claims that Beijing has been distancing itself from Russia, there is little evidence beyond Xi’s welcome public opposition to any use of nuclear weapons over Ukraine.

Putin, who signed with Xi the “no-limits” Russia-China pact in February, reaffirmed on October 27 that relations between the countries “have reached an unprecedented level of openness, mutual trust and effectiveness”, especially in military technology.

China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin responded that “we highly appreciate the positive remarks by President Putin.”

Xi met US President Joe Biden for three hours in Bali, where both sides appeared to wish to manage their inevitable competition before it could degenerate into conflict. Danny Russel, who ran East Asia and the Pacific under Obama, described it as a “deliberate effort to stabilise a dangerously overheated relationship”.

And the US, like every country on Earth, must find a way to live alongside China, preferably beneficially and, as far as can be ensured, safely.

It is becoming harder to do so while retaining full sovereignty since the party tends to believe its own security can only ultimately be guaranteed by restraining others’ sovereignty.

But painful economic realities are intruding everywhere in our pandemic-battered world, including in China, requiring such stabilising and welcome events as this week’s meetings with Biden and Albanese.

Rowan Callick is an industry fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout