Tech titans of Atlassian overtake Lowy in great decade to be rich

In the past 10 years, the rich have become richer at a faster rate than probably in this nation’s history.

It has been a great decade to be rich.

Household names such as Pratt, Rinehart, Lowy and Forrest have all added to their already considerable fortunes, and new magnates have emerged with fortunes built quicker than ever thanks to the internet and the rise of technology.

In the past 10 years, the rich have become richer at a faster rate than probably in this nation’s history. They survived the global financial crisis and have surfed mining and property booms, and mostly emerged unscathed from downturns in both sectors. They have thrived despite some tough times for manufacturing, made billions in technology ventures, and keep earning vast fortunes digging coal and iron ore out of the ground and shipping it overseas.

A decade ago, 30 people were measured as billionaires and were all born or based in Australia. Today that figure is north of 100 and includes Australian citizens who have made their fortune both here and in far-flung places ranging from London and New York to Delhi and Guangzhou.

There are industries, such as technology and online retailing, that have emerged as the hot sectors and others, such as traditional media and bricks-and-mortar shopping centres, that have resulted in big fortunes lost.

Wealth has changed rapidly this decade though, as the fates of the man dubbed the “sun king”, two fresh-faced software firm co-founders, a fitness instructor who was homeless but now is married to a global social media star, and a former prime minister once labelled the “member for net worth” show.

Then there is Frank Lowy, a legend of Australian business, who also has been at the forefront of some of the biggest changes in the ranks of the country’s wealthy elite. Ten years ago, retail magnate Lowy of Westfield fame was named Australia’s richest person with a fortune of $5.04bn.

It had taken Lowy exactly 50 years in business at his Westfield powerhouse he co-founded with John Saunders to build that considerable wealth. In what has been a remarkable career, Lowy had pioneered shopping centres in Australia, starting from a small delicatessen in Sydney’s Blacktown to overseeing what had become by mid-2010 a $30bn giant. Westfield then had shopping centres throughout Australia, New Zealand, the US and Britain, and its boss was at the top of his game.

Around the same time as Lowy became Australia’s richest person for the first time, two floppy-haired co-founders of a Sydney technology start-up called Atlassian were about to change the face of Australian business. It was a time when Mike Cannon-Brookes was still clean shaven and Scott Farquhar’s hair curly, and both were little known besides the odd mention in business pages charting emerging technology entrepreneurs in charge of mysterious-sounding software companies.

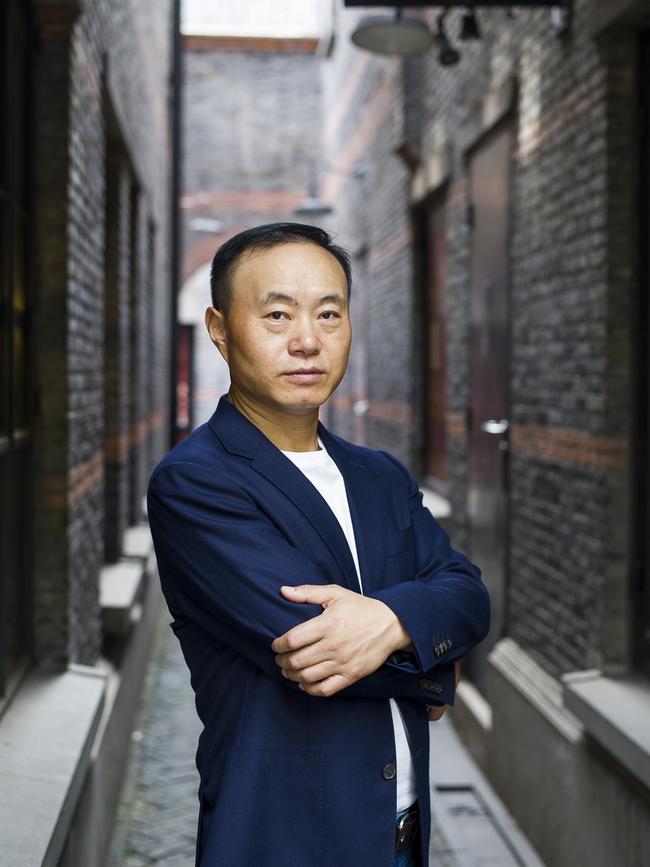

Yet back then, one of the hottest young names in business was Shi Zhengrong, the man known as the “sun king”. Solar panels were considered sexier than software. Shi founded his solar panel manufacturer Suntech in 2001, having moved to Sydney from China to undertake graduate studies in solar-cell research at the University of NSW. While there he took out Australian citizenship and after returning to China listed Suntech on the New York Stock Exchange.

At one stage in his early 40s Shi was a billionaire, but amid fierce competition Suntech declared bankruptcy in 2013 after defaulting on $US541m in bonds. Today, Shi is back in business with a fledgling company called SunMan, which makes lightweight solar panels that recently have been introduced to Australia. In August, Shi’s panels were unveiled on top of Sydney’s National Maritime Museum. But his name adorns wealth lists no more.

Shi’s rise and fall provides a salient lesson for young entrepreneurs, and it remains to be seen whether Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar follow the same path. But for now they have pulled off a remarkable achievement in wealth terms. In 2010 Atlassian, which Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar founded in 2002 after meeting in class at the University of Sydney, already had 225 employees looking after an estimated 20,000 customers in 140 countries.

Like Lowy, and countless entrepreneurs and business leaders before them, the Atlassian founders had backed themselves and come up with their own idea, in this case the project management tool Jira. But unlike Lowy and his fellow billionaires of 2010, Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar were about to get richer faster than ever. The duo in July 2010 closed a $US60m funding round with Silicon Valley venture capital firm Accel Partners, which subsequently valued the pair’s stake in their own company at a combined $314m. It was only the beginning.

As the decade unfolded, Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar would take on more funding, which kept increasing Atlassian’s — and their — value, capped by a groundbreaking listing of the software firm on the Nasdaq exchange in the US in late 2015, and a rapid appreciation of the company’s share price since.

In this year’s edition of The List — Australia’s Richest 250, published by The Australian in late March, Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar each had a fortune of $9.01bn, to place fourth and fifth respectively.

Sixth position was none other than Lowy, whose wealth is recorded at $8.92bn. To show how rapidly the world has changed in retailing terms, Lowy has exited Westfield completely in what will almost certainly be considered two masterly deals. First, in Marchlast year Lowy oversaw the $24.7bn sale of Westfield, which by now housed the company’s international assets, to French group Unibail-Rodamco. He made almost $3bn in the process.

The Westfield centres situated in Australia and New Zealand are held in the Australian Securities Exchange-listed Scentre Group, but Lowy sold his $815m stake in October to exit an industry that sustained his wealth for the best part of six decades. Now, the Lowy family is an investor and has entered more of a wealth protection, rather than creation, stage via its private Lowy Family Group. It will manage the family’s estimated $9bn fortune and hold it across various asset classes around the world. Unless things go alarmingly wrong, the Lowy name should maintain a presence among the wealthy elite for decades to come.

Yet while Lowy’s fortune could hardly be considered paltry, the fact he has already been passed in wealth terms by those two technology entrepreneurs who have turned 40 this year shows how quickly wealth can now be made thanks to the internet and the rapid advance of technology. To be blunt, in 10 years Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar have each made more than Lowy did in 60.

Whereas Westfield’s market was always local, restricted to wherever a shopping mall was situated and its surrounding area, Atlassian’s is truly global. Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar can work from their Sydney office and look after clients around the world. Even their property purchases, paid for in cash from some of the proceeds of the Atlassian float and some subsequent share sales, show the shift in how wealth is made and what success entails in contemporary Australia.

In September last year, Cannon-Brookes and wife Annie paid $100m for the Sydney harbourside mansion Fairwater, situated on an exclusive slice of Point Piper beachfront. Fairwater had been held in the Fairfax family for generations and was sold a year after the death of Lady Mary Fairfax, who at the turn of the decade was listed among the nation’s top 200 wealthiest people.

The Fairfax family by then had spent a good century at least as a prominent member of Sydney and Australia’s rich elite as its newspaper and media empire delivered regular and huge profits.

Yet by 2017, the year Farquhar shelled out $71m for the Elaine estate next to Fairwater — yes, he and Cannon-Brookes are business partners and neighbours — the Fairfax fortune was on the wane. Farquhar bought Fairwater from John B. Fairfax, ending 126 years of ownership of the estate by the Fairfax family.

The decade also has featured other names making, and then losing, big fortunes.

In the media sector alone, Bruce Gordon has lost his billionaire status and Reg Grundy has died and left behind an estate still being battled over.

Nathan Tinkler was once the youngest billionaire in the country, but after spending more than $300m building a horse racing operation and buying rugby league and soccer teams, he was made bankrupt in 2016 after his business empire collapsed owing $540m.

Though Tinkler has investigated getting back into the ownership of coalmines with the assistance of friend Gerry Harvey, he is still disqualified from directing Australian companies.

Others such as former DFO retail owners David Goldberger and David Wieland and the co-founders of Salmat, Peter Mattick and Philip Salter, who at one stage made big money from catalogues and other direct marketing initiatives, have seen their fortunes dwindle as their industries have been disrupted forever by technology.

Then there is Malcolm Turnbull, who before a stint as prime minister placed among the country’s richest people for several years. Turnbull was known as the “member for net worth” as a consequence of still sitting in parliament when ranked among Australia’s wealthy elite. His fortune was measured by his property holdings and a string of sophisticated investments in various funds around the world.

In 2010, Turnbull’s fortune was estimated at $186m, but that figure now would get him only halfway towards entry to the Richest 250. Turnbull is now in the wealth protection stage, having once been one of the original beneficiaries of the first tech boom when he and his co-founders sold internet service provider OzEmail for $520m in 1999.

There have since been several technology entrepreneurs who have become entrenched in the Australian wealth scene, including Seek co-founders Andrew and Paul Bassat and WiseTech’s billionaire boss Richard White who join Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar at the cutting edge.

Yet the tech baton is being passed on to an even younger, and globally savvy, group of entrepreneurs. The latest in that line of new tech entrepreneurs are Adelaide couple Tobi Pearce and Kayla Itsines, who at 26 and 27 respectively were the youngest members of Australia’s Richest 250 earlier this year.

Itsines is the face of their Sweat online fitness empire, which has boomed thanks to Instagram — the social media site that started in 2010 and on which Itsines has almost 12 million followers — and being at the forefront of the business of vanity around the world.

She and Pearce — who met when Pearce starting working out after dropping out of high school and then spending a period homeless — set up their online business in January 2014. Itsines compiled all of her workout tips after her “before” and “after” Instagram shots of her clients’ body transformations started going viral.

The tips went into a downloadable e-book called the Bikini Body Guide and formed the basis of the Sweat app today, which has become Apple highest grossing health app and has seen the business achieve annual revenue of $100m — and healthy profits.

Itsines now appears on breakfast shows in the US, where she also performs workouts at sold-out arenas.

Pearce, meanwhile, has visited Wall Street to gauge interest in raising money from investors.

Their success is more rapid than most have achieved in recent Australian business history, even when compared with that of Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar. The Atlassian duo were not worth more than $300m until they hit their 30s, whereas as Itsines and Pearce already have a business valued at $487m and headed towards what they hope is a $1bn valuation within a few years.

That landmark — known as achieving “unicorn” status — was recently achieved by another young entrepreneur in 30-year-old Melanie Perkins.

Her Canva, a digital design platform that gives users access to graphics, pictures and other design elements, is Australia’s highest valued “unicorn” after raising $US85m in October to give the company a $US3.2bn valuation.

That deal, for a company that was not even formed at the beginning of the decade, makes Perkins the country’s youngest billionaire.

The future of the Richest 250 has arrived already and, with the average age of most billionaires heading towards 70, the next decade and beyond is likely to be ruled by the younger tech titans.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout